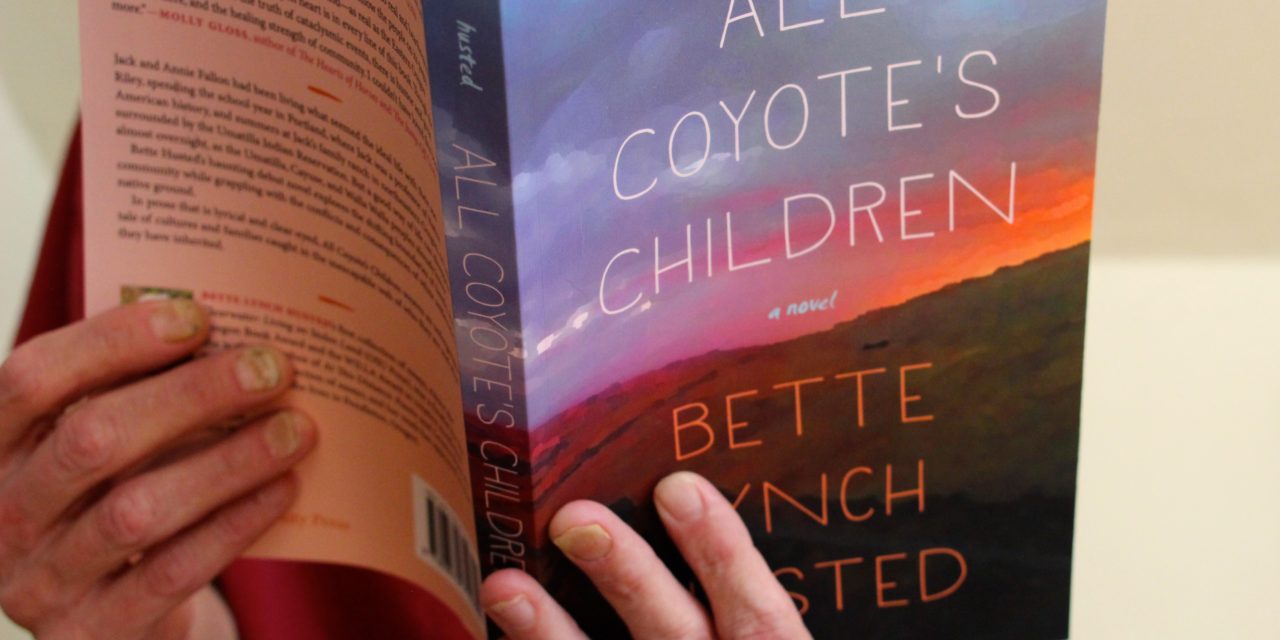

Title: All Coyote’s Children

Author: By Bette Lynch Husted

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, 2018

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard St. (541-484-3777); and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002).

By Daniel Buckwalter

“Everything impacts everything, and everyone is wrong … but everyone has a point.”

This line was fed to me in the 1990s by a now old man. I spent that entire decade in and out of group and individual counseling of many stripes, trying to get the deck chairs properly aligned on my personal Titanic. The mind and soul needed the work. It was (and off and on continues to be) hard labor. Yet this line has served me well. I come back to it still, though sometimes not until I bang my head against the wall in frustration.

Reviewer and writer Daniel Buckwalter; photo by Randi Bjornstad

Literally, I’ve seen the faculties dim and the heartbeat stop for people I loved. I’ve seen dreams, mine and others, vanish without a trace. I have seen otherwise dignified people – men and women I respect – attack each other in toxic situations and declare total war in public forums. I’m not alone, I know this. It is life, messy and confusing. Most of the time there are no easy explanations, no rhymes or reasons. There could be convoluted birth and background reasons or there just could be silence. Either way, none of it is good, just the rule. Confusion, masquerading as certainty and followed by weedy resentments, builds as a result.

Therefore, we walk a trail of forgiveness and acceptance by our lonely selves, trying to clarify our present and frame our future. It is hard work, yes, but it’s rewarding both intellectually and spiritually to those who take it on.

This brings us to characters I can cheer for in Oregon’s Umatilla County — Annie, Riley, Leona, Alex, Mattie and others — who set about to do this hard work in a wonderfully done debut novel, All Coyote’s Children by Bette Lynch Husted.

Husted, who lives in Pendleton, has previously published two collections of poetry and essays. One was a finalist for the Oregon Book Award and the WILLA Award in creative nonfiction.

The characters in the novel mentioned above (certainly Annie, her son Riley and Leona) are chasing ghosts. Jack (Annie’s husband and Riley’s father), Roy and Mary (Jack’s parents) are dead. They can’t explain anything, not that they could explain their secrets while they were alive, so they took their secrets with them to another realm and left the wounded loved ones behind to toil and search for answers themselves.

These characters (the living and the deceased) are normal, dignified people. Among the living, Annie and Riley are Caucasian, the others Native American. They have formed a close bond, and they are in this journey together. They are simply trying to find their way through tragedy and rebuild their lives through weeds of regret and guilt.

All Coyote’s Children, set mostly on a Native American reservation but with scenes in Portland where Jack taught, does not shy away from the institutional racism that Native Americans have faced, in the past or in the present.

The character of Casey is proof of that. Also, Riley and his best friend Alex are detained at the novel’s outset at the McLaughlin Center, a detention center for youth, on a nebulous charge of drinking and driving. That is the vehicle that drives the novel. The “counselors” at the center do their best to poison the mind of teenage Riley, in particular, with racist innuendo.

Yet, this is an endearingly spiritual novel. I found myself combing through biblical scripture about forgiveness and acceptance. Sometimes, though, it is Earth, her creatures and memory that create healing. It, not P0rtland, certainly is home for these characters, so I embraced the land and the animals, especially the coyotes.

I encourage everyone to do the same and read All Coyote’s Children.