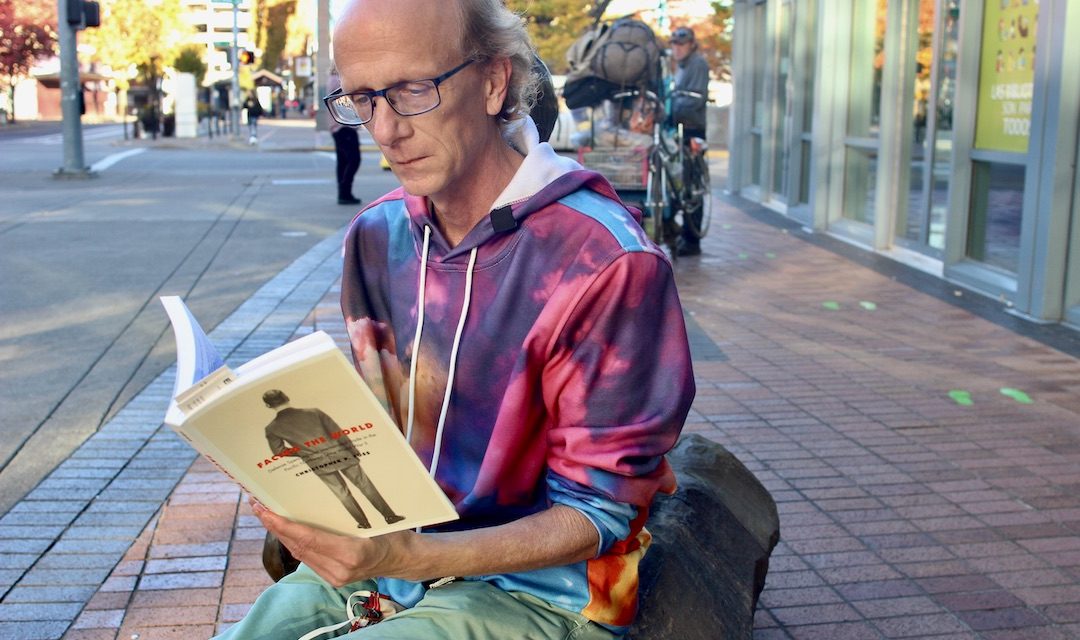

Title: Facing The World: Defense Spending and International Trade in the Pacific Northwest Since World War II

Author: Christopher P. Foss

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis (2020)

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-484-3777); and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

Tucked inside the first part of Christopher Foss’ detail-rich account of post-World War II growth in the Pacific Northwest through defense spending and international trade is an informational gem: A critical statement from the mid-1970s directed at U.S. Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington state about the voluminous defense spending he championed for his state, made by Victor Hanzeli, then-chairman of the philosophy department at the University of Washington.

Henzeli argued more than 40 years ago that the boom-or-bust economy of Kitsap County — all of the state, really — was taking a toll on the county’s citizens who, Foss writes, “were becoming intellectually and economically impoverished by this state of affairs.”

Henzeli stated in part, “People are no longer taking the opportunity during their formative years to broaden themselves, to ask questions other than how to make a buck, to think about the main concerns of humanity in a disciplined way.”

That’s our stark reality now, and in Facing The World: Defense Spending and International Trade in Pacific Northwest Since World War II, Foss expertly weaves the narrative of how state and federal politicians from Oregon and Washington first used WWII contracts, then Cold War contracts and finally, free trade, to turn a sleepy backwater of the United States to a thriving (for some) mecca.

The end of World War II was the start of an era of Pentagon largess in the Pacific Northwest, one framed first by Cold War fear of the old Soviet Union and then by the Vietnam War. As the Cold War began to wind down, the Pacific Northwest became part of an ongoing global trade exercise in a national effort to stabilize global partnerships.

Politicians fought tribally to seize the pork for their districts or states. It was a cut-throat race with winners (Boeing and Nike, for starters), a struggling working class trying to balance the boom-or-bust reality of a rapidly changing world, and losers (the Hanford Nuclear Site and its environmental devastation that Foss says will take generations to fully clean up).

Conservatives began to be fed up with government intrusion in the free market place as well as the infrastructure cost of growing towns that housed airfields and shipyards Liberal anti-war activists joined environmentalists in trying to put a halt to it all.

“Not all residents of the region benefited from the globally oriented development,” Foss notes. “As became increasingly clear near the end of the 20th century, the region’s poor, people of color, and even those concerned with the plight of the natural environment often found their voices silenced in the name of progress.”

All the titans of Pacific Northwest politics from the end of WWII to 2000 — many of them from my youth — are featured in Foss’ meticulous research and storytelling.

From Jackson to U.S. Sen. Grant Magnuson (the two were often called “the senators from Boeing”) and Rep. Tom Foley in Washington state, there came the tremendous burst of shipyard growth in Seattle and the Puget Sound area as well as Fairchild Air Force Base in southeast Washington.

Oregon countered with U.S. senators Wayne Morse (“The Tiger of the Senate”) as well Mark Hatfield and Bob Packwood and U.S. Rep. Edith Green. When trade was declared to be Oregon’s best chance raise its fortunes, there were governors Tom McCall, Vic Atiyeh (“Trader Vic”) and others to do Oregon’s bidding.

Oregon, Foss writes, didn’t have the geographic luxuries that its neighbor (and rival) to the north did for economic/military development. The result, to this day, is that Oregon is the poorer of the two states.

“From an economic and military standpoint, (Oregon’s) most valuable asset was the mouth of the Columbia River as it spilled into the Pacific Ocean,” Foss explains. “But Oregon was cursed by the stormy Columbia River Bar at the river’s junction with the ocean, which made large-ship passage in and out of Oregon difficult at best.”

Interestingly, Foss writes that Morse, a saint to peace activists and doves in his later years, was privy to talks in his early Senate career — and did not raise opposition to — the idea of locating the U.S. Air Force Academy in the Portland suburb of Canby.

That did not happen, but Morse helped lay the groundwork that Hatfield, Packwood and others would follow in the area of trade. From Asia to the Middle East (Gov. Atiyeh’s family came from Syria), Oregon politicians went globetrotting in search of what they believed to be sustainable industries (technology, foremost) that would compete with and even supplant the timber industry.

The results were mixed, and they rode sharply the ebb and flow of recessions and prosperity. And while technology has matured in the state, especially in the Portland area, Foss writes that as early as 1985, after Tektronix announced layoffs despite Oregon’s improving economy, Atiyeh’s “own administration acknowledged near the end of his tenure that, despite the influx of Japanese investment, the state’s old staples of timber, agriculture, and tourism remained Oregon’s three largest industries.”

Each state had ups and downs with their investments, and every politician in Foss’ accounting has had to confront the unintended consequences of defense spending and international trade, consequences that exist and are debated to this day.

Still, Foss writes that Oregon and Washington were blessed to have leadership that would attempt to raise the standards of living of its citizens, and he believes that this leadership now is lacking in our region.

“Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill once famously said that all politics are local,” Foss writes. “An era in the politics of this region, and perhaps in all regions of the United States, where locals had political power to sway national policy, seems to have passed.”

Yet it can be celebrated in Facing The World.