By Daniel Buckwalter

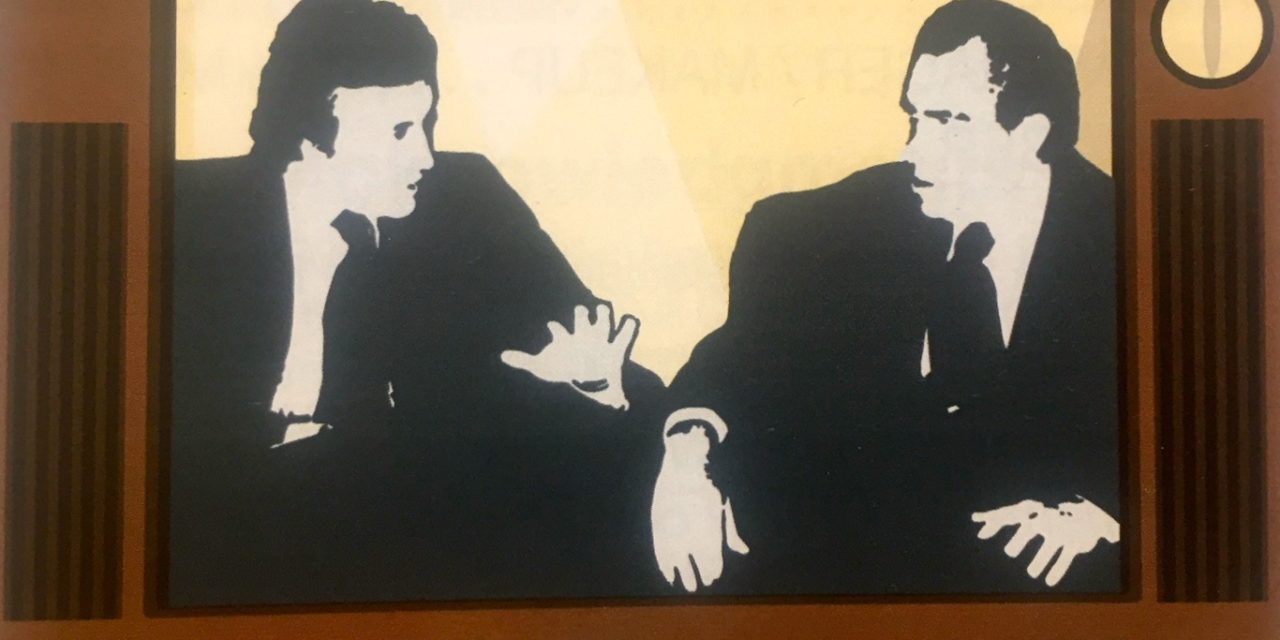

It’s near the end of Very Little Theatre’s production of Frost/Nixon, and the antagonists are exchanging farewells as gentlemanly (or -womanly) opponents should do. It’s a lost art.

This has been a grueling process of negotiation, research and practice for both men, and endless hat-in-hand fundraising for David Frost.

Everything is now done.

The six hours of televised interviews are finished. Richard Nixon (Mike Hawkins) is “controlling the space” through the initial interviews. He is at his rambling best on topics he has long mastered and in a cadence he understands. He has Frost (Damon Noyes) on the defensive.

Frost counters in the last segment, which is all about Watergate. Point by excruciating point, Frost nails Nixon on the cover-up, and the disgraced former president is now flustered and sweating.

Finally, Nixon concedes that mistakes were made, crimes were committed and that he let the American people down.

It is riveting television in 1977. A celebrity talk-show host — a playboy lightweight in the eyes of many — is stripping the haughty criminal bark off a former president in front of an entire nation, and Americans are shocked and engrossed. Ratings are through the roof and journalist are parsing every word.

Both men needed these interviews to resurrect their careers, and with it their identities. Frost is the winner. No one remembers the initial four hours of interviews, just the interview about Watergate. Frost will ride high for years to come.

Nixon will wander in the wilderness until his death in 1994, never again to enter the arenas he craves. Frost believes Nixon wants this role. He sees it in a late night phone call from a black-out drunk Nixon on the eve of the Watergate portion of the interviews.

It’s the pivotal scene of the play. Nixon is about to meet the villain inside of him. He can’t escape it. This role — powerful man in the wilderness — is penance for the sins committed by the Quaker for which greater payment could not be exacted because of President Gerald Ford’s pardon.

The enormity of long-term consequences will take time to develop. First, Frost and Nixon have to say their farewells. Each man has his shadows. Nixon’s is Manolo Sanchez (Steven Shipman), the manservant who attends to all of the president’s needs. Frost is arm-in-arm with Caroline Cushing (Samantha Cross), his latest girlfriend whom he meets on a flight to Los Angeles.

Pleasantries are spread thick. Frost even offers a gift. As the secondary characters depart, Nixon pulls Frost aside. He has questions for the talk-show host. Is Frost comfortable being known as a playboy? Is Frost comfortable on a pedestal surrounded by airy, chattering crowds with no substance? Could he be more than what he’s shown?

Stripped away to the core, is Frost comfortable in his own skin?

Yes, says Frost. This is, I think, why Frost “wins” the interviews. Frost has his moments of self-reflection, but he will not wallow in self-doubt like Nixon. Most of all, he’s not afraid of competing voices in his ear if it serves his self-interest. He will accept tension. He’s not afraid to learn and grow, and Nixon exposes Frost early on as a man who needs to learn and grow fast.

This is where the great print journalist James Reston (Blake Beardsley) and respected TV journalist Bob Zelnick (Larry K. Fried) come into play. They are the street-tough advisers, and they want a beheading. Frost wants surgery. He sees theater, pulling the audience in and out, establishing narratives. Wonky journalists are not great at this, but Frost has a touch for it and is Nixon’s equal as a result.

The unintended long-term consequences of the Frost/Nixon interviews are two-fold.

First is the cottage industry of personality-driven journalism. As long as there has been television news, there have been personality-driven journalists, yes, but cable network news has polluted the waters beyond brackishness. Pick a network, and everyone wants that ratings home run. The more outlandish, even amateurish, the better. There are not enough Restons and Zelnicks offering street smarts.

Secondly, it’s rare today to find people in the public spotlight willing to show much contrition for inappropriate words or actions. Even when they do, it’s often viewed as phony because they appear primarily to be trying to protect their “brand.”

That includes politicians. Let me put this way: Donald Trump was a young man when the Frost/Nixon interviews were taped. Yet ten minutes listening to a Trump press conference today reveals much the same method that Nixon honed somewhere along the line — do not apologize, monopolize the conversation whenever possible, and immediately redirect criticism back on your opponents. In the end, that didn’t work for Richard Nixon.

It appears that Americans may be as shocked and engrossed by today’s political shenanigans as they were in 1977, but too much of the back-and-forth now is revealed through tweets and sound bites instead of in-depth, one-on-one interviews based on facts and intent.

VLT’s Frost/Nixon serves as a reminder of the value — indeed, the necessity — of that kind of probing, which seems to have been replaced these days by endless rounds of what amounts to reality television excerpts.

It’s not a change that bodes well as a foundation for the future decision-making of the American voting public.

The seats for this play at the Very Little Theatre should be filled every night by people who care more about political reality than about political theater.

Frost/Nixon

When: 7:30 p.m. on Aug. 10-11, 16-18, 23-25; matinees at 2 p.m. on Aug. 12 and 19

Where: Very Little Theatre, 2350 Hilyard St., Eugene

Tickets: $19 regular, $15 for senior citizens and students and for all Thursday performances; available in advance at the box office, 541-344-7751, from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; or online at TheVLT.com

Details: Assisted-listening devices available on a first-come basis