By Daniel Buckwalter

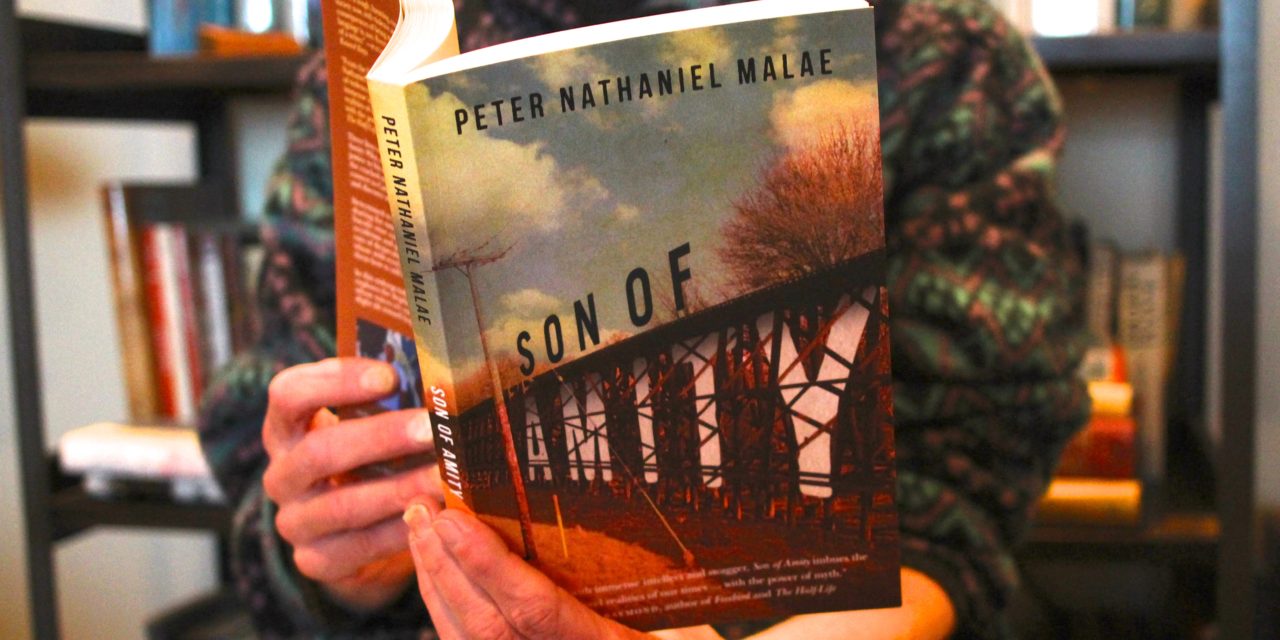

Title: Son of Amity

Author: Peter Nathaniel Malae

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis (2018)

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-4845-3777); and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

It exists in all communities, the drive-by frame of mangled art that one speeds past on the way to more bucolic settings.

There’s nothing to see here. There’s nothing to touch.

Please don’t touch. The stains are permanent.

It is poverty, and it is rooted in the eye of the beholder. Commonly in our culture, it is seen in economic terms, though there is a spiritual kinship that can accompany the economic component.

A person (or family or community) at whom poverty’s derogatory slang is directed may not see it, or even care. “This is who I am,” the person may say, and he or she may make allowances for it to stay in place. It is their only perceived power, because the person inside poverty’s hold understands that it rarely grants upward mobility without strong compassion on one end and fierce determination to change on the other. It is trust, and one must meet the other. It is difficult labor, and it is rare.

More often than not, a man or a woman in the grip of poverty sets down their anchor. From there, the lifestyle — with its methodical and vicious cycle — takes hold. There are limited choices, and there is no end in sight.

This is generational poverty, with children hit the hardest. A passerby knows it when he or she sees it, and most who see it eye it with contempt. Further, in rural America, those living in poverty can’t escape the looks of disgust. There’s nowhere to hide or any real help to escape. So they live the life and by necessity make it their own.

The consequences of this generational poverty (especially in the child character, Benji) is seen in real time with honest, gritty detail in Son of Amity, the latest novel by Oregon author Peter Nathaniel Malae.

Malae minces no words in describing the decades-long emotional, psychological and institutional abuse handed down to the three main characters of the novel: Pika, Michael and Sissy.

Pika is the half-Samoan ex-con who is serving time in California at the novel’s start. He and members of his extended family have been in and out of jail and prison throughout their lives. Pika alone has been in prison long enough that he makes no apologies for it. The lingo, the life — the street justice — by now is embedded in him. He is, in fact, ready to deliver street justice to the man who raped his sister (Sissy). He also is aware, I think, that street justice runs both ways, and that he can die in an instant. He has accepted this because knows no other way.

Michael is Amity born-and-bred, and he carries it always. At age 18, he has no future. He has nowhere to go. He has a cruel, belligerent mother who has her own limitations and is ever-present, yet he is tied ball and chain to Amity. So he joins the Marines. He serves five tours in Iraq after 9/11, which is five tours too many.

He returns home for good in the spring of 2006, paralyzed by PTSD. He can’t move out of bed for quite some time upon returning home, even to see his girl, Sissy. It will take some time for his mind to move forward, but only after his legs can’t take him forward anymore.

And there is Sissy, Michael’s wife and Pika’s sister. She, through Catholicism, is trying to reorganize her life, to have a life. Yet she, too, has an overbearing mother (“a bottomless fount of flowing pessimism,” Malae writes), a small town that “knows” her and a self-loathing that takes her two steps back in any development for every half-step forward.

Together, they know only verbal or physical assaults or retreating into shells. Everything is buried resentment, followed by violence or retreat. It’s a cycle that never ends.

They find themselves in a house in Amity, with Benji (Sissy’s young son — remember the rape — and Pika’s nephew), trying to be the spirit that brings them together. He’s only five years old. He loves football, idolizes his uncle and wants his parents to get along.

Benji wants everyone to get along. He is the sponge that absorbs the good; he is the sensitive soul. He knows no other way until Thanksgiving in 2010 when a hail of gunfire cuts down Pika in the house by homies from San Jose, California, seeking vengeance for past deeds. The novel ends with Benji losing his innocence. He’s not yet six.

The lifestyle, with its methodical and vicious cycles, takes hold and never releases its grip.

All of this takes place in Amity, Oregon, located in Yamhill County and with a population of 1,614, according to 2010 Census figures. The village is 83.9 percent Caucasian, 15.5 percent Hispanic and (surprising to me) 0.6 percent Asian and Pacific Islander. It is near McMinnville. Wineries and fine homes financed by inherited and out-of-state money dot the landscape. The underbelly is the poverty, punctuated by drug use, notably meth.

Amity, however, is nearly every small town in Oregon — and too much of America. The main characters (Pika, Michael and Sissy) note this in their own halting ways.

In Malae’s hands, it is as insular as any small town in Oregon or throughout America, yes, but the author also does a wonderful job of developing characters others would think of as less than themselves and giving them room to evolve spiritually. I want the characters to grow and succeed. The trials are too much, though, and they have their lasting effects.

Son of Amity is not an easy read, but it is well worth the effort to take an unsparing look at the difficult lives of the men and women left behind in generational poverty. They need — and deserve — justice.