(Above: Sarah Grew’s work includes photographs and found objects mounted on board and covered with a layer of wax; photos by Paul Carter)

By Paul Carter

In Sarah Grew’s imagination, time is an elastic concept. It flows into the future, but it just as easily hurtles backward far into the past. And then it folds back on itself to unexpected points in between.

Call it Grew’s Conundrum: How to express this convoluted thinking in her art.

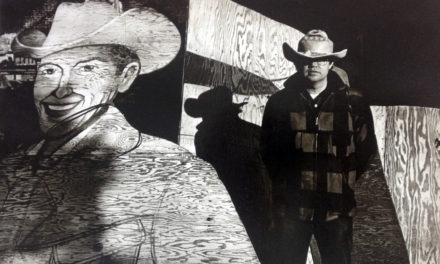

The artist Sarah Grew in her studio

Fortunately, the artist has many tools at her fingertips, because she is both a painter and a photographer who reimagines the two mediums in mind-bending ways.

Photography sometimes holds primacy in her work, while other times hovering subtly in the background of her paintings, especially when challenging our perceptions of the nonlinear passage of time.

She is adept at both digital and analog image making, as well as using processes that date to the beginnings of photography, such as Cyanotype and Van Dyke brown printing. Photographs that use both her own and found images often can be further enhanced with the application of wax layers or layered with found objects.

“I’m a closet science nerd,”Grew quipped during a recent interview in her airy south Eugene studio.

It all started in childhood with a Kodak Brownie camera and a darkroom where she was welcomed by her father and grandfather. She was 5 years old when she began learning about the magic of the analog darkroom. A Brownie camera loaded with 12-shots rolls of film taught her to be thoughtful and deliberate about what she chose to photograph.

“There is a history in my family of painting, music, photography, and writing,” she recalled. “Photography has always been a part of how I think.” Yet, she describes her photography “as a way of drawing.” Moreover, it is important to her work precisely because it is an expression of time. There is a “temporal nature” even to clicking the shutter.

Grew’s skills in early analog photography were pushed along by work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Bancroft Library conservation lab at UC Berkeley, where she spent a year printing glass plate negatives from the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco.

Though photography is important in her work, she insists she “presents myself as a painter.” Less interested in straight-ahead photography, Grew claims not to have the skills to mimic, say, an Ansel Adams landscape. That sort of image making “felt overwhelming to me,” she said.

Examples of Grew’s cyanotype prints, a 19th-century process that preceded the daguerrotype

Yet there is this matter of time and her preoccupation with how to portray it. Photography—the capture of time— fits right in with the projects she dreams up.

For exampe, cyanotype, a process that preceded the daguerrotype, results in images with 19th century character. Invented in 1842, cyan blue images are made using readily available chemicals and can be printed on almost any paper.

Similarly, Van Dyke printing also involves chemical solutions applied to paper, with a brown or sepia image as the result. Grew was attracted to the old processes because the images instantly suggest the eras in which they were invented.

A blue- or brown-toned image, possibly one with obvious references to the past, then embedded in an oil painting, combines the two media to “express temporality through memory,” Grew explains.

For example, in a painting titled, “Erased Landscape — Blue Orange,” a mountain horizon stretches across a 24-inch by 72-inch aluminum sheet. The image consists of seven repeated layers of cyanotype images applied to the metal substrate. The horizon of the abstract painting is bisected by repeating verticals. The “sky” appears infused with warm light, the “foreground” with cool-toned light. Also in the foreground, a wavy line mimics the movement of an electrocardiogram, a recurring motif Grew uses as another representation of time.

Her intent is to bring time into view.

“Recently, I have begun a process-oriented experiment about time and the horizontal line as a timeline in which I create digital negatives of my drawings that I print using cyanotype technology on hand sensitized paper,” she explains on her web site. “The print is coated with clear acrylic and then painted …. The idea is that each layer of the work uses materials and technology of different eras and thus accentuates temporality while fusing time into a series of painted gestures.”

The complexity and abstraction of the work demands slow, careful viewing and, for the viewer, repeated viewing. “The next time you see it,” Grew said, “you might see it differently.”

Grew will revisit this combination of painting and photography with an upcoming project that starts with photographs of petroglyphs in eastern Oregon.

However, her photographs are not always cloaked behind paint.

She presents a more accessible work in “Little Jewels and Small Worries,” in which sepia-toned, nostalgic-looking photographs are imbued with texture and depth created with a covering of wax. “It ages the photograph. It makes it feel not real,” she said. “It gets people to question what they see and what they know.”

Grew used abstracted photographs of lynchings in America

to illustrate text from a play by Wallace Shawn

Far afield of any other of her projects, Grew makes a searing political statement with images that illustrate “The Fever,” the text from a play by Wallace Shawn. The play is a monologue on suffering and oppression in a Central American country.

The work is a stark meditation on the “ways we kill people,” Grew said.

She used some of her own photographs juxtaposed with familiar images, including one of the hooded Abu Ghraib prisoner. But most powerful are two images based on photographs from this country’s history of lynchings of African-Americans. Grew used pictures taken from the postcards that were printed to celebrate these lynchings. She abstracts them by obscuring the backgrounds, but the hanging bodies are no less disturbing. It is a powerful set of images and another glimpse into how this artist thinks about time.

Sarah Grew’s work will be on view in 2018 at the Umpqua Valley Art Association.

To see more of her work, go online to sarahgrew.com

Sarah Grew’s “Erased Landscape — Blue Orange” combines

photographic methods and painting.