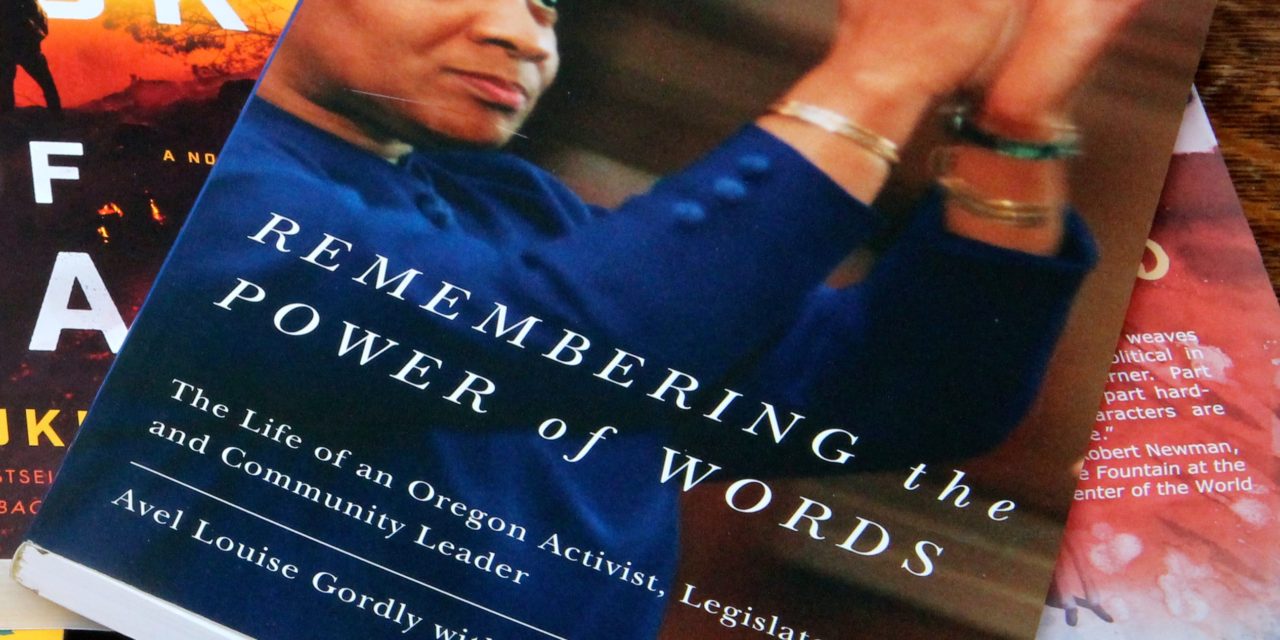

Title: Remembering the Power of Words — The Life of an Oregon Activist, Legislator and Community Leader

Author: Avel Louise Gordly, with Patricia A. Schechter

Publisher: Oregon State University Press

Details: Published in 2011 as part of a series on Women and Politics in the Pacific Northwest, edited by Melody Rose

By Daniel Buckwalter

Peace.

Peace to stand tall and still in the hail of words delivered and internalized, almost all them challenging, at best. This peace – and its accompanying spiritual grace to speak the truth of your soul quietly and with dignity – resonates to all from the past and present, and it is aspirational.

Few can pinpoint its definition. You know it in a person when you see it. I’m not certain anyone can attain this peace consistently, but it doesn’t stop the determined from reaching for it. The moments of spiritual clarity are rare and hard won, so they should be celebrated, especially among those who serve their community.

This brings us to Avel Louise Gordly and her 2011 memoir, Remembering the Power of Words — The Life of an Oregon Activist, Legislator and Community Leader, written with Portland State University colleague Patricia A. Schechter.

Literary reviewer Daniel Buckwalter says Avel Louise Gordly’s memoir “reads like an affirmation note for women, people of color, and the collaborative activist process.”

It reads like an affirmation note for women, people of color, and the collaborative activist process, but that’s the point. For too long, Gordly and other men and women in our society have had their voices silenced or, perhaps worse, nicked by alleged allies who believe they mean well.

“Overcoming the silences that doom us to spiritual and physical death is essential for recovery and survival, especially in Oregon,” Gordly writes, “where a liberal and progressive white-majority culture can smother and choke off our voices.”

This becomes evident to Gordly, a born-and-raised Portlander, during her undergrad years at Portland State University.

“As I shifted my educational standing and employment prospects, white folks raised their own questions, like: ‘Are you from here? You don’t seem like you are from here.’ I’m never sure exactly what that means, but the effect is one of suspicion, alienation, and even rejection.”

So Gordly’s memoir can still speak for African Americans, other minorities and all women.

Most notably in the public sphere, Gordly (who now teaches in the Black Studies Department at PSU) was the first African-American woman elected to the Oregon State Semate, in 1996. She retired from that position in 2008. Prior to that, starting in 1991, she served in the Oregon House of Representatives.

Her run up to elected office included stints with Portland House of Umoja, the American Friends Service Committee, the Urban League, the Black United Front (a particular favorite professional time for her) and the Oregon Department of Corrections (not a favorite professional time for her).

She learned the collaborative process, to give voice to others and, slowly but surely, became a leading voice herself. Gordly also came to understand that stories matter more than wonky position papers.

“For some people language is linear, but linear thinking doesn’t work for everybody,” she writes. “When bridging cultural divides, some time needs to be invested in storytelling. Stories tell us who we are and where we are heading collectively.”

This includes Gordly’s childhood, which had its rough patches. There was the uncle who molested her and the father who migrated to Portland from the Jim Crow south (Texas), whose idea of punishment for Gordly and her sister came from another era and way of thinking. He loved his daughters, I believe, but he did use tree branches for whips when he perceived his daughters for “talking back.”

“Growing up, finding my own voice was tied up with denying my voice or having it forcefully rejected and in all of that the memory of my father is very strong,” she writes.

There also were two marriages – the first after she became pregnant while still in high school – and bouts of depression, some of which were near crippling. But Gordly had the support of her activist communities, always, and they are the people who encouraged to run for elected office in the early 1990s.

Collaboration and the self-centered world of state politics don’t mix, of course. The jolt of Salem was, I’m sure, an eye-opener for Gordly, but she recalibrated and has a solid list of contributions for her time as a legislator.

The foreword to Gordly’s memoir is written by Charlotte B. Rutherford, who notes that the book contains a picture of Gordly holding a photo of members of the NAACP’s Portland branch after passage of the Oregon Public Accommodations Act in 1953. It took 18 legislative sessions – a full 36 years – to get that bill passed. The work is never-ending.

“First,” Rutherford writes, “the picture conveys Avel’s feeling that she is standing on the shoulders of those who came before her and that she has carried the legacy of those early activists forward in her roles as activist, legislator, and educator.”

Remembering the Power of Words can still stand as a template for inclusiveness, grace and grit. I can’t pretend to know the outcomes of this year’s mid-term elections or the 2020 general election, but I do know that if women generally (and women of color, especially) make strides in those arenas, they would do well to learn about — and emulate — Oregon’s Avel Louise Gordly.