The Book

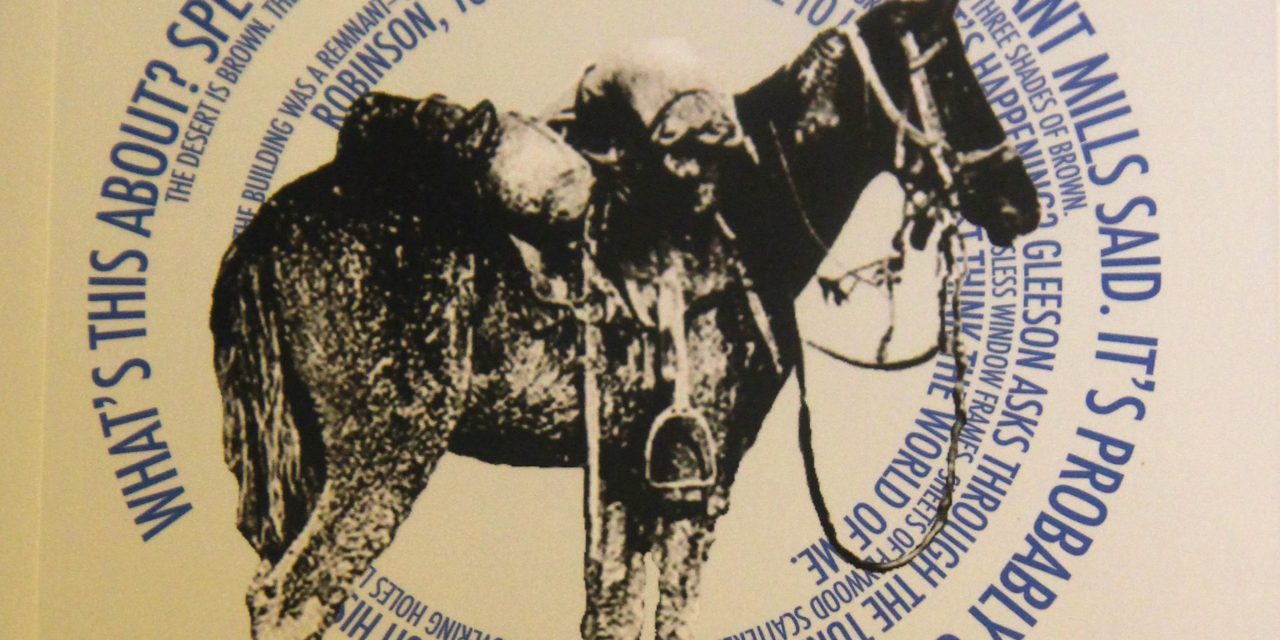

Title: The Horse Latitudes

Author: Matthew Robinson

Publisher: Propeller Books

Awards: A 2018 Oregon Book Awards Finalist/Ken Kesey Award for Fiction

Available: J Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway, Eugene; 541-342-2002

By Dan Buckwalter

In 2004, as combat troops poured into Iraq, U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld spoke of reporters embedded with units and their reports from the field. He urged Americans not to read too much into “the slices” of news from these reports, that the war – any war – has staging ports all over the region and world, moving parts.

Somehow the phrase “through a soda straw” was born, and its concept has found its way into Matthew Robinson’s outstanding debut book, a collection of short stories called “The Horse Latitudes.”

The book is a 2018 finalist for the Ken Kesey Award for Fiction, which will be announced in April at the Oregon Book Awards.

“The Horse Latitudes” follows Robinson — a Portland-based writer and now a writing instructor at Portland State University — and his Oregon National Guard unit through a deployment in Baghdad. This is well after “Shock and Awe.” It’s also well after “Mission Accomplished.” There would be more daily battles, of course, and “The Awakening” and “The Surge” are to come. This now is a police action. “America is established here – this is a garrison environment,” the XO barks in the opening essay.

It also is a lean, unsparing fictional tale (more on that later) about life in a silo that few Americans know of. The draft, of course, was abolished in 1970, and as of January 2016, there were close to 1.4 million people serving in the U.S. armed forces. That’s a mere 0.4 percent of the population, according to the Defense Manpower Data Center, a body of the Department of Defense. Out of sight, out of mind for a select few men and women who serve in America’s far-reaching outposts.

And for God and Country? Mostly, the reasons are more primal, as it is with the character Specialist Gleason. “I’m just here for the college money. And to get those spurs.”

Robinson does an eloquent job of seeing all the patrols and all the characters (including himself) from a high elevation. He can disconnect himself from the mundane and the terror. He is a reporter in that sense. It is the template for the fiction, for which the names of Robinson’s platoon mates have been changed. That brings us to the character Staff Sergeant Hicks. His real name is Stone, and we know this because Robinson liberally inserts Mr. Stone’s critiques after almost every story. Mr. Stone is not a fan of Robinson’s take on the deployment, and he makes his feelings known.

“I read your story. It’s s***,” writes Stone after the opening story of the book, “Garrison Environment.”

“You think you are the only one who can tell a story??” Stone writes after the story “Pedestrians.” “I can tell my own f****** story, son. You can shove that Hicks up your ass.”

Then there’s this from Mr. Stone, after the story “OPSEC”: “All right, I’m not writing any stories down. There’s no point. But you shouldn’t either. Not if you’re only going to write me as a drunk mess. You’re missing the goddam point, Matty. I have to live with it, that blood and money and gut-shot Hajji. I’ll never *****. You can’t even write it? Do better.”

Mr. Stone has a fair point in that last passage. The primal in all of us is one-dimensional. It’s all about surviving, especially magnified in a soul-less war zone. Everyone is more than that, of course. But not everyone in Robinson’s platoon will make it home alive, either. God and Country will define one, as it has for others too often in wars past.

That’s why “The Horse Latitudes” is important, and why it matters and we all should read it, to break through the silo and attempt to erase the insanity of war.

I wish “The Horse Latitudes” well in the upcoming Oregon Book Awards. I highly recommend it.