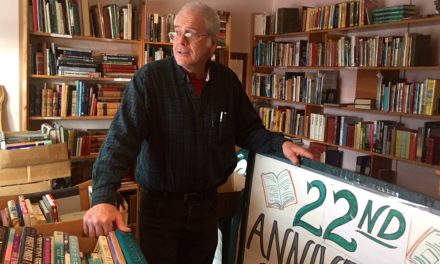

(Above: Infrared photograph by Linda Devenow, part of an exhibit at the O’Brien Imaging gallery.)

By Randi Bjornstad

Put as simply as possible, infrared photography uses special film or filters to capture wavelengths of light that range far beyond what the human eye can see. As a result, photographs may look far different from what would be considered “normal” in terms of color and texture.

It’s not a recent development. As long ago as 1910, an American physicist and inventor named Robert Wood started experimenting with the process, and it quickly became not only a novelty but incredibly useful. Infrared images required extremely long exposures, and during World War I, when toxic gas was introduced as a chemical weapon by the German Army, infrared photos could penetrate that fog, revealing the demarcation between buildings, bridges, bodies of water, and vegetation to guide military response.

In the 1930s, camera and film manufacturers made infrared film available to the general public, and the military also continued refining the process, which continued to be a vital tool during World War II.

In the decades since, infrared photography has become an art form. It lends itself especially well to landscape photography. It has become a tool used to detect older paintings covered up by later works of art without doing damage to either. It’s been a popular method for creating “psychedelic” album covers and promotional materials for pop stars and other entertainment groups.

Photographer Linda Devenow

Longtime photographer Linda Devenow began honing her passion for infrared photography just four years ago, after having started pursuing film photography in the 1990s, including working for the Walt Disney Studios as photographer for all Walt Disney TV Animation employee events, and later expanding her work to include head shots and family portraits.

Doing infrared photography back then with film “was arduous,” Devenow recalls. Even with improvements in digital cameras, which can be used for infrared photography either by converting the camera itself from a normal to an infrared filter or by using an external infrared filter, “getting into it was haphazard,” she says.

But then in 2018, “I went to the Maude Kerns Art Center and saw a show of infrared photography, and for me it was a game-changer,” Devenow recalls. “It was the feel, the craftsmanship, the ability to look at something in a different way, to see the unseeable. I said I was going to do that.”

At the time, Devenow was studying at Lane Community College to switch careers and become a computer security analyst, “but that show completely changed what I wanted to do.”

Because of the different wavelengths captured by the infrared process, the resulting photographs can look deceptive, but they are real, she says.

“Some infrared pictures make the landscape look like wintertime, when it’s actually spring, and infrared also does a lot to the sky that you wouldn’t see otherwise.”

Although the learning curve was steep, Devenow quickly made significant progress in mastering infrared skills, resulting in several group and solo shows.

“At the beginning, I just showed pictures on my phone, and I had only one framed picture,” she says. “Then all of a sudden I had these offers for shows, and I needed 25 pictures. I was terrified that I couldn’t do it, but I didn’t want to say no, I wanted to say yes. It was a real roller coaster of emotions, but I managed to do it in time.”

Photo taken by Linda Devenow in February 2020 as part of a show of infrared photos taken over two days during the pandemic.

She describes her current show at the O’Brien Imaging gallery as “extremely personal,” growing out of a period when she suffered the trauma of losing several beloved cats in a short period of time, plus contending with covid-19.

The photographs in the show were taken on only two days in 2020, first on Feb. 9 and then on April 26. The February pictures are from Junction City, Harrisburg, and the Finley Wildlife Refuge. The April photos are from the Middle Fork Willamette River area.

With the exception of one photograph, Devenow says, this is the first time these images have been printed, matted, and framed.

Memories: 2/9/20 and 4/26/20

When: Through Nov. 26, 2022

Where: O’Brien Imaging, 2833-B Willamette St., Eugene

Hours: 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday; call 541-729-3572 to confirm open hours

Artist information: devenowphotography.com