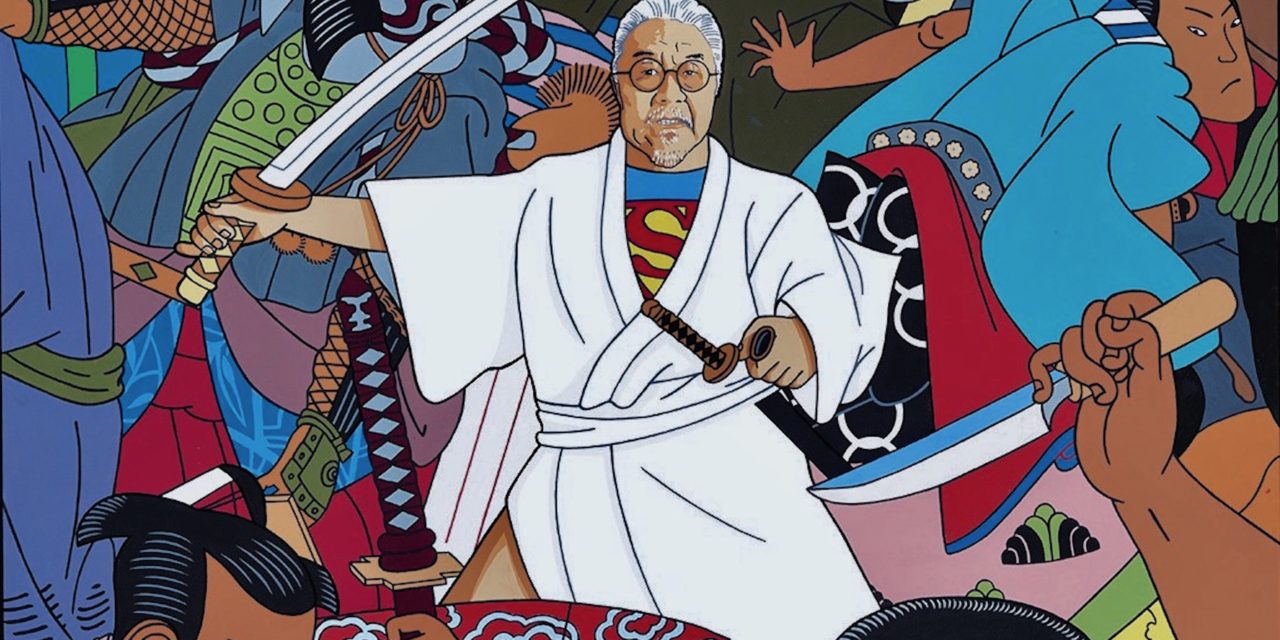

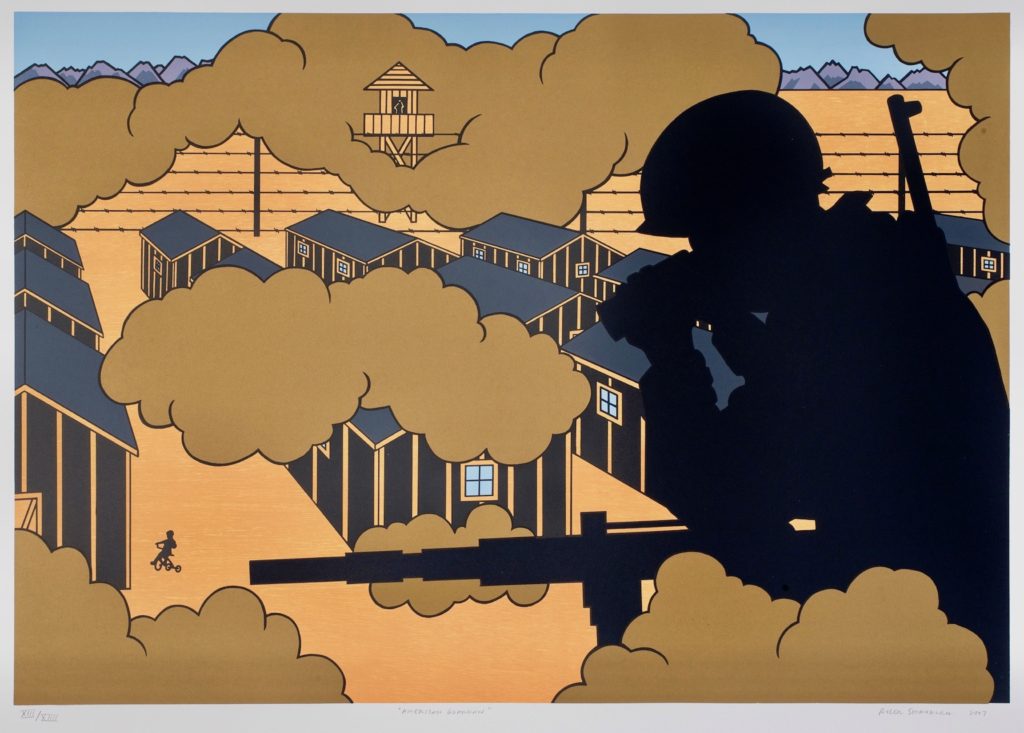

(Above: Detail from American vs Japanese #3 by Roger Shimomura)

By Randi Bjornstad

The ideal way to see Roger Shimomura: By Looking Back, We Look Forward, a recently opened exhibit at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, is to tag along with Anne Rose Kitagawa, who curated the show and has a special relationship to its subject.

And it’s possible to do just that — at 5:30 p.m. on Wednesday March 4 — when Kitagawa leads a guided tour of the show. Her knowledge and insight add a richness to the experience of viewing artist Roger Shimomura’s work, which turns his Pop Art forté into an accessible and yet pointed look at a deplorable episode in U.S. history, the detention of 120,000 Japanese-Americans in what amounted to 10 concentration camps during World War II.

Roger Shimomura often pictured children in the internment camps as silhouettes

Shimomura was a toddler in Seattle when the war began, and in 1942 he and his family were among those incarcerated in the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Hunt, Idaho, until their repatriation at the war’s end and their eventual return to Seattle after a stint in Chicago during which his baby sister, born in the camp and never healthy because of the incarceration, died in early childhood.

Those early memories and impressions never left him, and through his later education in the arts — at the University of Washington and Syracuse University, followed by 35 years on the faculty at the University of Kansas — Shimomura meshed his interest in Pop Art with the trauma of those early years to develop a particularly effective way to allow people now to consider what happened then as well as the degree society is still open to permitting such degradations.

“This was kind of an aspirational project for me — I have admired his work for years,” Kitagawa said, acknowledging that her own family has its history of internment in the camps. “There is no question that his work is very pointedly political. He presents it in the colors and style of Pop Art, so it deceptively approachable — but it definitely has teeth.”

The back story for the show dates to 1882 and the existence of anti-Asian laws in this country, including the Chinese Exclusion Act, Kitagawa said.

“Whenever there has been a societal downturn, it seems that immigrants are blamed,” she said. “This has happened to many groups in this country and abroad, and it certainly happened to Roger Shimomura’s family during World War II, but there’s no doubt that the issue is still appropriate throughout the world now. He has turned his beautiful art toward examining the marginalization of people who are considered forever foreigners.”

Kitagawa points out things for people to watch for as they examine Shimomura’s work, such as the number of times children are painted as silhouettes — almost as ghosts — without details to portray their individual faces or clothing.

He also frequently overlays similarly faceless guards carrying weapons on his paintings, looking down at their more brightly drawn prisoners in the camp below.

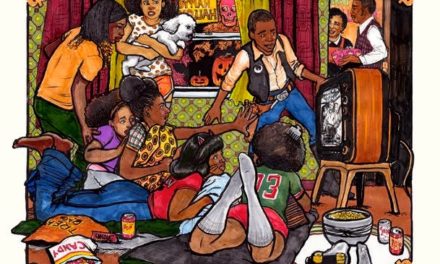

One theme of Shimomura’s art compares the way people look compared with the ideal of the dominant culture

“I admire that he can channel the dismay and trauma that he experienced as such a young child in a way that can lead people to not just to appreciate his art but to learn from this story of American history,” Kitagawa said.

Not that the end of the internment camp was the end of Shimomura’s profiling as someone American enough, she recounted.

“Even after all his education and when he was teaching at the university in Kansas, he went to buy something, and he was told by the clerk that they didn’t extend credit to ‘Indians.’

“He said, first of all, he was not Indian, and second, he was a professor at the university, not that any of that should matter,” Kitagawa said. “But he had so many experiences of being treated that way, of being profiled.”

Shimomura often puts subtle self-portraits into his work, and he eventually turned to presenting his Pop Art with a Japanese style, “in part because people expected that of him,” Kitagawa said. “People would say to him, ‘Now finally your art looks like you.’ “

One of his most striking paintings includes a melange of classically Japanese Samurai-style figures brandishing weapons, with Shimomura standing in the center, his hair gray and his face with beard and moustache, dressed in a white kimono-cum-bathrobe open to show a Superman costume underneath.

“I don’t try to decode his message too much, just to appreciate what he does,” Kitagawa said. “He has unexpected ways of using figures to express something completely different, to show a documentary view of the world in a totally different style.”

Roger Shimomura: By Looking Back, We Look Forward

When: Through July 19; special guided tour by curator Anne Rose Kitagawa at 5:30 p.m. on Wednesday, March 4

Where: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, 1430 Johnson Lane on the University of Oregon campus, Eugene

Gallery hours: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Wednesday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday through Sunday

Admission: $5 adults, $3 ages 62+, free to children in grades K-12 as well as college students, UO faculty and staff, and museum members; free to all the first Friday of each month, and admission by pay-what-you-wish on Wednesdays from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m.

Information: 541-346-3027 or jsma.uoregon.edu/

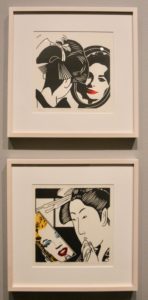

American Guardian is typical of Roger Shimomura’s depictions of the Japanese-American internment camps, showing silhouetted guards with guns overlooking the camp and barracks.