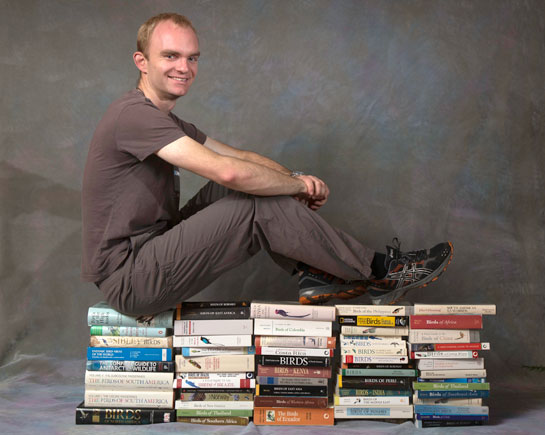

(Above: In order to carry out his quest for the 2015 record for most bird species spotted in one year, Noah Strycker created digital files of dozens of bird identification books to serve as resources.)

By Randi Bjornstad

Noah Strycker’s passion for birds — some might call it an obsession — began when the Eugene-area boy was only about 11 years old, and his fifth-grade teacher at Oak Hill School in Eugene put up a bird feeder outside the classroom window.

That led to bird feeders at home, with bird books to help identify avian visitors, and for Strycker, now in his early 30s, the die was cast. The rest of his youth was spent watching birds and starting a list of each species he encountered. He graduated from Oregon State University with a bachelor’s degree in fisheries and wildlife and a minor in fine art.

The kid known as Bird Boy had become Bird Man.

A hobby becomes a vocation

Eventually, Strycker spent three months in Antarctica, part of a team studying penguins at the Camp Crozier scientific research station. He based his first book, “Among Penguins,” on his experiences of that trip.

His second book, “The Thing with Feathers,” grew out of a maturing interest that went beyond identifying and listing birds to studying behaviors particular to different species, from the communal raising of chicks in some wild species to the “pecking order” by which ordinary chickens take their turn eating in another.

But soon after, a new adventure beckoned — harking back to identification and lists — and on Jan. 1, 2015, Strycker set out to break the world record for how many species could be seen and documented in one year.

Strycker spotted the Whitehead’s Trogon in Borneo

The effort, which has the moniker “The Big Year,” started about 1890 when a couple of people in Ohio started tallying as many birds as they could in the county where they lived. By the 1930s, “birders” were competing to see the most species throughout North America. Eventually, the craze went international.

In 2008, the record was just over 4,300 — not quite half of the 10,000 species assumed at that time to exist — set by a British couple, and that remained the record until Strycker took up the challenge, determined to cross the halfway mark of the number of the world’s bird species.

His journey took him to all seven continents, and he recounts his adventures and misadventures in his latest book, “Birding without Borders,” with the subtitle, “an obsession, a quest, and the biggest year in the world.”

By the time he finished, on Dec. 31, 2015, he not only had broken the previous record, but bested it by more than 2,000 species, for a total of 6,042. It takes 50 pages of small type in the back of “Birding without Borders” to list all the species he saw.

The first was a cape petrel in Antarctica, on Jan. 1. The last was a silver-breasted broadbill in India, on Dec. 31.

More than a list

These days, Strycker spends a lot of time speaking to groups about his Big Year experience, as well as hiring on for several months each year as a bird expert on seagoing Arctic and Antarctic tourist expeditions. He also is associate editor of “Birding” magazine.

But when he gives his talks about his Big Year adventures, he talks about much more than birds.

“I usually start with travel stories,” Strycker said. “My Big Year and the subject of this book is a story about people as much as anything.”

The trip included “going to some sketchy places,” and most of the time he was accompanied by local birders interested in his project.

“Linking up with local people was key to the success of the whole trip and keeping out of trouble,” Strycker said. “Once, we ended up in a forest in the Philippines on (the island of) Mindanao that was controlled by rebel groups. I asked the guy I was with what would happen if we ran into them, and he said, ‘Oh, I know all the rebels — I would just say hi.’ “

Another time, he was scheduled to meet a man named Hugo for some strenuous birding, but for several weeks before he arrived, his messages to Hugo had gone unanswered. When Strycker got to his destination, he learned that Hugo recently had died of injuries suffered in an automobile accident several months before.

“That was really shocking,” he said, and besides the loss of a friend he hadn’t met in person, it made him even more aware of how dependent he was on colleagues all over the world who shared his passion for birds and bird identification.

But for the most part, the year of traversing countries and continents went fairly smoothly.

“I was lucky — I had mishaps but no real catastrophes,” Strycker said, beyond an illness or two and some vehicle breakdowns that slowed his progress a bit.

Strycker takes a selfie while dashing down a gravelly hill on the Brujita — The Little Witch — in Colombia

He also came across some highly unusual modes of transportation, including the time in Colombia that he traveled via Brujita, translated literally as “The Little Witch.” The vehicle consisted of seats fastened to a cart that sat on old railway tracks and were powered by a rider on a motorcycle.

There were some scary moments, including in Tanzania when the safari truck he was riding in at 70 m.p.h. blew a tire and careened off the road into the brush.

“Nobody was wearing seatbelts, but it was pretty flat and no one was hurt,” he said. “There were so many things that could have happened, but fortunately they didn’t. I think the fear of the unknown is the biggest fear of all.”

Strycker financed his year-long trip with an advance from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the publisher of “Birding without Borders.”

“It was set up as three-year project,” he said, “one for the traveling and two to produce the book. I kept notes all along the way, but I also did a daily blog on the Audubon site. If I added all that up, it would have been at least two full-length books.”

The Leica camera company also sponsored his trek, providing binoculars, a spotting scope and a camera.

Records made to be broken

Impressive as it was, Strycker’s bird-sighting record fell the very next year, in 2016.

“I knew about halfway through my trip that a Dutch guy named Arjan Dwarshuis was planning to try to break my record,” Strycker said. “He was following what I was doing, and he tweaked my itinerary in some places he thought he could see more birds in a short time.

“We’re almost the same age, about four months apart,” Stryckersaid. “He’s really kind of like my Dutch twin. I said, ‘Go for it.’ “

Strycker doesn’t plan to do the Big Year again, but he’s not done with birding, either.

“I was afraid that I would get really burned out during that year, but I didn’t,” he said. “In fact, I think I came back just as obsessed as ever.”

His latest book project, a collaboration with photographer Joel Sartore for “National Geographic” and titled “Birds of the Photo Ark,” is due out in March.

Noah Strycker talks about “Birding without Borders”

Thursday, Jan. 11 — 7 p.m., Tsunami Books, 2585 Willamette St., Eugene; information at 541-345-8986

Tuesday, Jan. 16 — 6 p.m., Eugene Public Library, 100 W. 10th Ave.; information at 541-682-5450

Noah Strycker with several thousand of his best penguin friends in Antarctica; the polar regions rank high among his favorite places to study birds and enjoy a challenging environment