(Above: A “self-portrait” of artist Caroline Young at her desk. After a recent diagnosis of ADHD, the 20-year-old discovered the importance of creating more order in her life.)

By Randi Bjornstad

Artist Caroline Young, who’s just 20 years old and in her third year at the University of Oregon, describes herself as “very, very extroverted.” Maybe that’s why spending an hour or two sipping a cold iced chai to her iced vanilla latte flies by like so many minutes.

Young grew up in Houston, Texas — “My dad was in oil and gas” — until eighth grade, when the family of two parents and three kids moved to Colorado.

“I enjoy new places,” she says, then confesses that nonetheless, “Before we moved I made my dad bribe me with promises of new furniture and stuff.”

At age 9, young Caroline Young had her first paid commission, painting a mural on a friend’s bedroom wall.

All her life, she knew that her parents considered her “the artistic kid,” which probably was a logical conclusion given that by the age of 9 she was painting a mural on the wall of a friend’s bedroom, at the behest of the child’s parents. “They even paid me,” Young remembers.

She also had a sewing machine and a mannequin for her 3-D creations. “I was obsessed,” Young admits. “If I could imagine it, I would figure out how to do it. I would think of it, do it, and be done.”

By her senior year in high school, she was the head of design for its literary magazine, and once at the UO, she immediately declared a major in advertising.

“I guess it’s very common that you’re not encouraged to pick a major right away — I’m told half of people switch — but I knew I liked art and design and psychology,” Young says. “And one of the main reasons I picked Oregon is that it’s on the quarter system instead of semesters. I actually wish it could be even shorter — I tend to get bored. The only thing that I don’t get bored with is art and graphic design.”

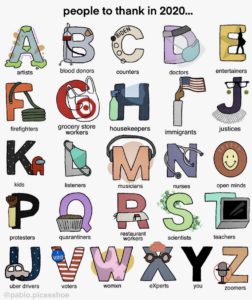

Young’s alphabet poster celebrating an A-Z list of heroes of the pandemic.

But when the pandemic struck, and the isolation of quarantine set in, she suddenly couldn’t focus on her studies.

“I had worked at the (UO) Daily Emerald for two and a half years, and I had just stopped before the pandemic because I felt I had done everything I could do there,” Young recalls. “I had always said I was bad at school and good at working — it’s that combination of focus and attention.”

In that sense, the enforced isolation proved useful, because Young pursued help for what she was experiencing and earlier this year was diagnosed with ADHD — attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. That shed a lot of light on all of her growing-up experiences, including periods of anxiety and depression that she had associated with her difficulties at school.

“It has helped me a lot to know what has been going on for so long,” she says. “Now I realize that by understanding this label, it doesn’t mean I’m not trying hard enough, it just means I need to find ways to work around it. I had the opportunity to take medication, but I decided at this point in my life I can cope and re-figure ways to do what I want and need to do.

“I really have an understanding now of how I work — I sometimes joke that I’m just part of what I like to call the ‘mental health generation’.” Young says. “But by understanding it, I also know you can text me and say what you need created, and I can do it for you. If you have a vision in your head of what you want, I can make it happen.”

That versatility has led her to do pet portraits, illustrations for a children’s book, and a part-time, long-distance design gig for an ad agency in Colorado. “I’m really big on reaching out to random people and trying to sell them on me,” Young says, a confidence that also led to a branding design project for a co-working space in Costa Rica.

“That has been the greatest thing about the pandemic, I think,” Young says. “You don’t have to be anywhere, but you can connect with so many people that you are really everywhere.”

Some of her pandemic realizations were very simple ones, such as her sudden recognition that she needs “a lot of structure” to thrive. So she created a dedicated workspace, rearranging her room to accommodate a desk. She also established a much firmer schedule for work time and mealtime.

“When I found out about the ADHD and called my parents and told my dad, he said, “Oh, you must have gotten that from me,” Young recalls. She describes herself as very self-reliant and very analytical, preferring to cope with personal challenges by herself.

“I am on my own, independent, and not super-attached to family,” she says. “I love them, but I want to deal with things on my own.”

The artist created posters whose proceeds benefited the Black Lives Matter movement; this poster celebrates books by Black authors.

One way Young does that, of course, is through her art. During the past year or so, she created an alphabet poster identifying people to thank for helping the country and the world get through the pandemic.

She also created several Black Lives Matter-related posters — one celebrates books by Black authors — and donated the proceeds to the Minnesota Freedom Fund.

“That helped me feel that I wasn’t just a silent voice in a large crowd,” she says.

Although she works in a variety of mediums — acrylic paintings, resin creations, advertising design, stickers, portraits of pets and people, fabric creations — “I think my best medium is probably digital,” Young says. “My dream job is to work for a magazine, that’s what I really love. I’m not officially working with one currently, so I just create that sort of thing for fun.”

Oddly enough, despite her lifetime of creativity, it’s not until recently that she has thought of herself as an artist.

“Over the last year, I have spent a lot of time focusing on my own opinions and choices in terms of who I am and what I want to do,” Young says. “It’s been kind of the creation of ‘me’ as a person and an artist.”

Naturally, she has a website where she shows and sells her work. It can be found online at carolinebyoung.com.

Artist and student Caroline Young; photo by Randi Bjornstad