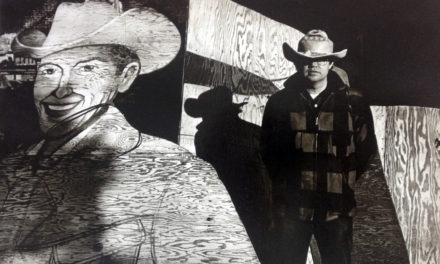

(Above: Author Cai Emmons, photographed while on a book tour several months after her diagnosis with Bulbar Onset ALS.)

Update: Cai Emmons carried through with her intention to control the time and manner of her own death utilizing Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, which allows terminally ill people to self-administer a lethal medication prescribed by a physician. Oregon was the first state to establish that right; the law went into effect in 1997.

Emmons died at 4:12 p.m. on Monday, Jan. 2, 2023.

Posted by Randi Bjornstad

Cai Emmons is a well-known (and prolific) writer of novels, several based on science and the human-caused changes that threaten planet Earth in dramatic — and potentially disastrous — ways.

Emmons, who lives in Eugene, Oregon, with her husband Paul Calandrino, also is a person with her own intensely personal challenges stemming from a diagnosis early in 2021 of Bulbar Onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. She has used her blog to trace the physical, mental, and emotional progression of her illness and her philosophical approach to it. Her website and links to her blog posts can be found at https://caiemmonsauthor.com.category/blog/

When asked if Eugene Scene could reproduce the following recent — and particularly emotionally wrenching — blog post, she responded with one word: Sure!

(Search for “Cai Emmons” on eugenescene.org for previous stories about her work.)

By Cai Emmons

Every day I circle through the ground floor of our house with my walker. My exercise tour! Beginning in the bedroom, where the “cockpit” (aka the bed) is the center of my activity these days, I advance in my ground-gripping slippers, careful step by step. A Bishi chime, a gift from a friend, hangs from my walker, sounding delicate music as I go. I push through the bedroom door into the hallway where family photos are mounted on the walls—grandparents, parents, sisters, husband, son, a couple of myself as a child and a teenager.

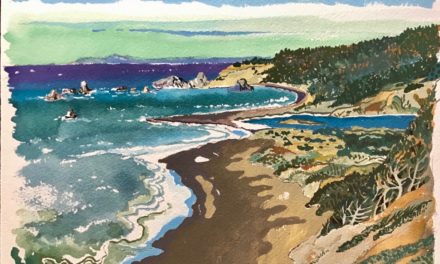

Cai Emmons and longtime partner and husband, playwright Paul Calandrino, on the ocean bluffs near Yachats, Oregon

I hang a right into the kitchen. This is my husband’s fiefdom, the place where he makes sourdough bread and baguettes and chicken-with-the-olives and paella and chicken adobo and crepes and souffles and berry galettes, to name a few of his many superior dishes. He has been keeping the kitchen immaculate in the last few months since he stopped cooking for me. I can’t remember when I last opened the refrigerator or took anything from the cupboards, but I know where everything is, and I could easily instruct a stranger where a specific plate or glass or pot or pan lives. The melamine plates that don’t break. The Rachel Maddow glasses. The handmade ceramic mug I gave my mother and reclaimed when she died. The kitchen also displays some cherished artwork: a photo collage of me and Paul made by the filmmaker Sandra Luckow, an encaustic painting with flecks of gold made by a friend, Molly Cliff Hilts, who died a couple of years ago, and a recently acquired print of a painting Joan Baez did of Patty Smith (both people I admire). I pause at the counter to rest and see if I have any mail that Paul lays out there then I move my gaze to the adjacent living room.

I push forward along the path Paul has cleared for me, past the sectional couch that is large and cozy enough to accommodate Ben and several of his friends overnight, over the rug I bought for myself years ago when I was newly divorced, a symbol of my independence and the freedom to choose whatever I liked. Above the fireplace is a large painting of a New York swimming pool painted by a good friend in New York, Medrie McPhee. That painting has been with me for decades, just like Medrie’s friendship. I arrive at the Christmas tree that Paul and Ben decorated while I watched. I unwrapped the ornaments and laid them out on the table, and they hung them. They are ornaments we’ve had for years, some from my grandmother, some from my New York days, some that Paul and I have acquired or been given over the years. They all have a story. Most years it is my job to dismantle the tree. In early January I remove the ornaments and wrap them individually in pages of The New York Times and The LA Times that date back to the 80s and 90s. I can’t bring myself to throw out those scraps of paper, tattered and threadbare as they are. This year the job of taking down the tree and storing all those ornaments will fall to someone else. I suspect the archaic newspaper will soon be trashed.

I sniff the tree, a fragrant Noble Fir. I sniff again and move on. I pass the foyer where, in a corner, there are boxes of things from Ben’s childhood that my ex-husband brought for me to sort through. I haven’t had the focus or the physical strength to do that, so they have been there for a few months now. Another job that someone else will have to do. Most of it, I suspect, will be tossed though I hope my sisters rescue some of the old books we had as kids.

I head down another hallway, passing Ben’s former bedroom, now doubling as a guest room and my study, which I rarely use as a study. I don’t enter. There is too much in there I would want to organize, rearrange, reorder: the boxes of my books that need labeling, the piles of papers that need to be filed, the blankets that need to be folded. The room isn’t really a mess, but I could spend days in there Marie Kondo’ing.

I pass my sister’s exquisite quilted wall hanging, and another riveting encaustic painting made by a dear friend I’ve known for decades, Andrea Schwartz-Feit. It occurs to me I’ve been lucky to know so many wonderful artists. Some of my best conversations about writing have been with my painter friends who bring a fresh perspective to the whole enterprise of making art.

Now I join the initial hallway that delivers me back to the cockpit. I sit quietly for a while, regarding the room. Since I’ve been moving around less freely, I’ve gathered the objects I need closer: the writing pads and pens, the spiral notebooks with musings, the lap desk, the books, the wrist braces and hand gloves, the eyedrops and Listerine spray, the neck pillow, the heating pad…I could go on. It behooves me to have various things within reach because then I don’t have to request them so frequently. Needing help to do formerly minor things like lifting my computer, or turning on my electric toothbrush or headlamp, makes me mindful of the myriad small things we do in a day to organize the objects around us. We use objects for almost everything we do. For all our self-maintenance activities like bathing and dressing and cooking and eating and sleeping, etc. As well as to enact whatever we do for work. I know a physicist whose primary mode of research is thinking (he researches flocking behavior), but even he needs to eventually employ a pencil and paper to write down equations.

Paul and I once stood mesmerized at the Portland Zoo by an orangutan who was moving around his enclosure fetching slabs of cardboard and bringing them to a corner where he lay on them, testing them for comfort. He remained still for only a few seconds before he was up again, in search of more cardboard or a banana. His home base was directly on the other side of the glass from where we were standing, giving us a closeup view. We watched him do this for at least half an hour, maybe more, and when we left we compared notes. We both remarked on how human he seemed in trying to organize his environment, arranging his objects just so.

The piles around me horrify the caregiver who comes in to shower me. She shudders at the sight of such clutter. I tell her it wasn’t always like this, but I can tell she doesn’t believe me. We laugh.

I have begun to imagine in more detail the moment in less than a month when I will inject a lethal substance into my feeding tube that will bring on my death. I will be saying goodbye to everything and everyone who has made up my life. I picture myself vanishing from the room where I write, leaving behind a void in the bed in the shape of myself, like the chalk outlines made by police. All the objects I consider personal, even private, will be left behind. I have made peace with my books and clothes being sent to Goodwill, or to whoever needs or wants them, but the thought of all my writing-in-progress, as well as my notes, being read is painful. All that bad writing and sophomoric thinking on display! It is a task for my remaining days to make peace with this. As far as I know I have no closeted skeletons, but still I shudder. It feels like the worst kind of exposure. I would love to have the time and energy to review all that stuff, but I don’t. I know I mustn’t fret over what I can’t control. I have three and a half weeks to stop fretting. Begin now, Cai.

No one wants to get overly attached to objects, and the Christmas season reminds us about that danger. If you’ve lived a certain number of years—or if you’re a Millennial or Gen Z’er born into a world of climate catastrophe—you know that more stuff won’t make you happy and won’t help the world. And yet, we humans, inventors of tools, live in a world in which we need objects for survival and well-being. What I learned from watching that ape, as he moved about in apparent dissatisfaction, was something about the importance of finding balance—having a few right objects in their right places.

For now I’ve found a kind of chaotic balance. Amidst the chaos I still know where everything I need is. The question that remains is: Can I see that even the most personal of objects will be of no use to me on my next journey?

Happy Holidays!

Love, Cai

Cai Emmons, who still maintains her philosophial inquiry as she navigates the ravages of Bulbar Onset ALS, diagnosed nearly two years ago.