(A nearly life-size shark is one of 80 sculptures created by Angela Haseltine Pozzi to bring attention to the danger discarded plastic represents to creatures of the oceans; photos courtesy of The Washed Ashore Project in Bandon, Oregon)

By Randi Bjornstad

It seems that everything in Angela Haseltine Pozzi’s earlier life somehow pointed her in the direction of what she’s doing now — reclaiming (so far) 28 tons of plastic from the ocean and turning it into sculptures that on the one hand wow the senses with their artistry and on the other horrify because of where they originated.

“I was very lucky to be raised by artists,” Haseltine Pozzi says. “My dad was the head of the Washington State art commission, and my mom also was an artist — I grew up with art as my first language.”

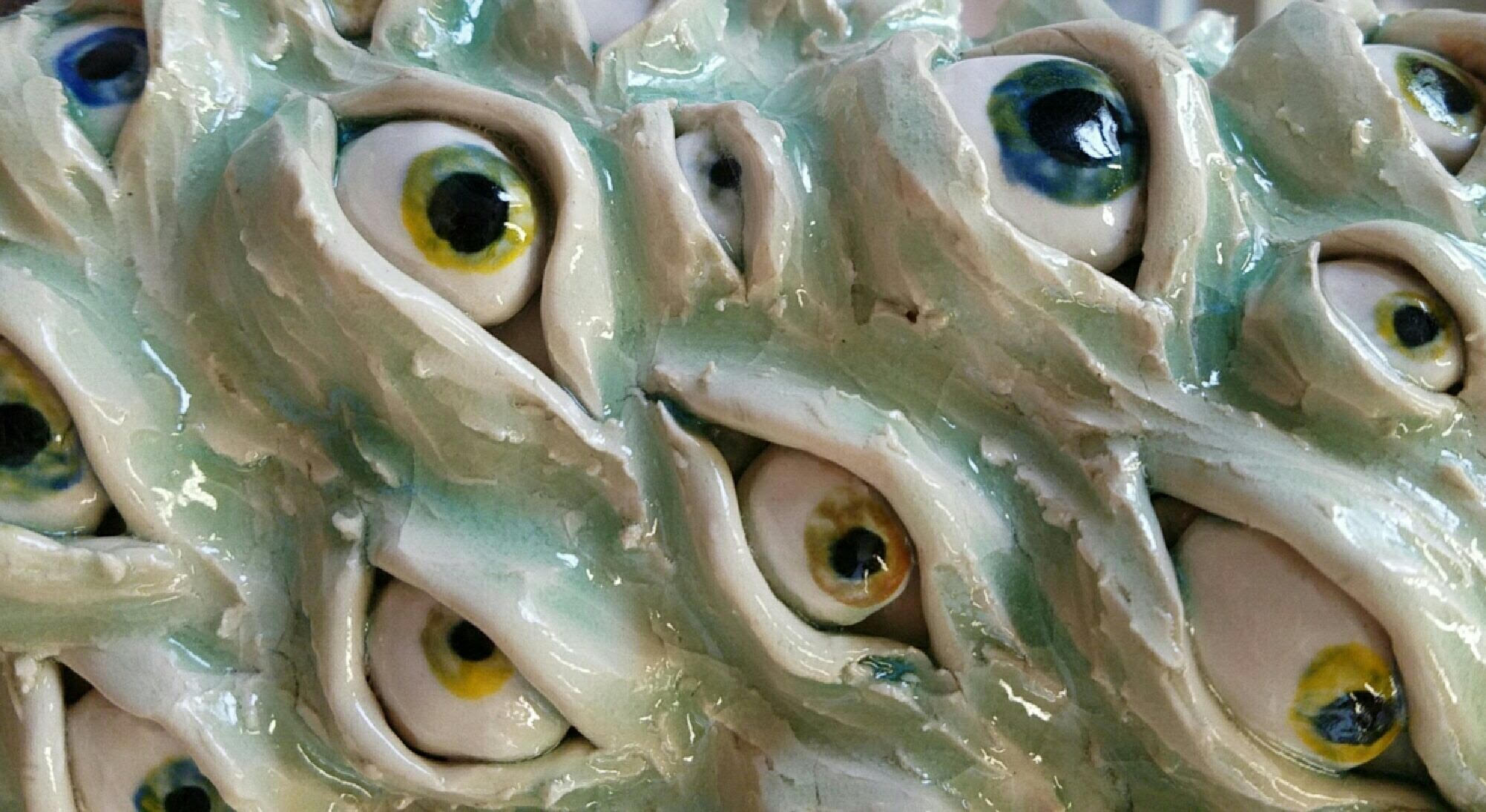

A detail from a large sculpture of a salmon shows the wide variety of plastic detritus that ends up discarded in the ocean

She also loved nature, she recalls. “I was identifying plants by their Latin names from a very early age.”

Haseltine Pozzi was born in Portland, but when she was 3 years old, her father took a new job, and the family moved to Utah.

“We kept our close connection with Oregon, though, because my grandparents lived in Bandon, and we spent entire summers there where they had a little cabin on a lake,” she says. “They had a little cabin on a lake, and my favorite memories of life are of Bandon.”

Her other grandparents lived up on the north Oregon coast, “so I had the ocean on that side of the family too, and I was always intrigued with it.”

In adulthood, she became an art teacher, which she did for 30 years “in public schools, private schools, at Portland State University, with students of all ages and all abilities,” Haseltine Pozzi says.

When she was about 40 years old, her mother died, “and at that point, I decided I needed to switch and make art my career,” she says. Always interested in “repurposing” castoff objects, she began to frequent thrift stores for materials she could turn into art and sell.

Then another tragedy befell her at age 47 when her photographer and arts-education husband was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He underwent surgery, then suffered a stroke and died, leaving her a widow with a teenage youngster.

“At that point, I was really searching for purpose in my life,” Haseltine Pozzi says. “I decided I needed to move back to Bandon — I dropped everything and went, and I walked and walked the beaches every day.”

It was during those healing jaunts that she began to notice all the garbage thrown onto the beach by the tide, and Haseltine Pozzi began to have an inkling of her future purpose.

Mother and chick Adelie penguins are among the creatures commemorated (in junk plastic) by Washed Ashore

“I did some research on the issue, and about then I also began to see all the tiny, tiny pieces of plastic that were everywhere along the beach,” she says. “I was sick to my stomach.”

But she also grew convinced that a major part of the problem was that the public did not realize the gravity of the situation, “and I thought that if I could use my teaching experience to make them aware of the problem, also use my art help save the ocean, I would find the purpose in my life.”

That all started in 2010, and the result was 13 sculptures within the first 10 months of starting The Washed Ashore Project. A decade later, the project has processed 28 tons of plastic from the ocean and created 80 works of art in its quarters in Bandon’s Old Town district.

“We have a staff of eight, and everyone has health insurance,” Haseltine Pozzi says proudly.

Many of her sculptures are larger than life. They are created completely from the vast amounts of discarded plastics that have been carried sometimes thousands of miles through oceans and then deposited on beaches.

The artworks take the the form of creatures — sharks, puffins, jellyfish, turtles,

Even polar bears are affected by discarded plastic in the ocean environmentpolarbears, seahorses — whose continued existence is threatened by humans’ insatiable appetite for acquiring and then discarding the trappings of civilization.

Haseltine Pozzi’s passion has grabbed the attention of zoos, aquariums, museums, and botanical gardens throughout the United States, where the Washed Ashore creations often are exhibited for periods of six to 18 months.

“The organizations usually lease the pieces from us, and we travel to their locations with the works, install them, and educate their staffs about the issue and the amount of plastic that consumers throughout the world waste and discard,” she says. “Then they can share the information with people who see the sculptures.” she says.

One of the most important aspects of her work is “to get people to realize is that this is not necessary,” Haseltine Pozzi says. “As consumers, we can make other choices that can save the natural environment and these animals.”

The Washed Ashore sculptures have been exhibited or planned for Disney World — “They actually pledged to reduce their own plastic footprint after seeing our work,” she says — as well as Sea World in Orlando, Fla., The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., The Florida Aquarium in Tampa, Fla., the Oakland Zoo in California, the Oregon Zoo in Portland, and of course at home in Bandon. Several pieces also have been displayed in the plaza of the United Nations in New York City.

Because of advertising and marketing, people worldwide “have been sold a bill of goods,” she says. “We’ve been taught to think that things that are cheap, fast, and shiny are good — we haven’t been taught that earth tones are beautiful and sustainable. So people might use something for five minutes and discard it, but then it lasts as waste for 500 years.”

She acknowledges that accepting this kind of responsibility can be “overwhelming and depressing” when people realize what humanity has done to the earth and its wild creatures.

Just a smidgen of the 28 tons that The Washed Ashore Project has gathered since 2010 and turned so far into more than 80 large sculptures

“So we have to be kind to ourselves as we change our priorities. It takes time to get new habits, but it is something we have to do to save the earth. And one of the best ways to accomplish it is to get children involved — they are the best hope and conduit for change.”

To that end, Haseltine Pozzi has created a curriculum for teachers to use in their classrooms. Washed Ashore also has many videos on its website, washedashore.org, to bring attention to the issue and encourage people to take up the challenge at family, neighborhood, school, and community levels.

“When I started Washed Ashore in 2010, there wasn’t much scientific evidence to back up what I was learning, that everything is endangered by our practices of using and discarding plastics,” she says. “But just 10 years later, it has been established as absolute fact. The plastic issue is now endangering the entire food chain, from land to lakes to rivers to oceans — there are microplastics everywhere.”

It sometimes seems insurmountable, but she believes The Washed Ashore Project and its sculptures are helping to make a difference.

“I like to think we have had an effect on people and the way they think about what they are doing to our world,” Haseltine Pozzi says. “So far, 28 million people have seen our exhibits in person, and I have seen people really cry over what they realize.

“I do believe we have influenced the discussion.”

The Washed Ashore Project

What: A nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness through art of the world’s growing plastic pollution problem and its effects on the oceans and the creatures that inhabit them

Where: Harbortown Events Center,325 Second St. SE, Bandon, Oregon

Contact: Telephone 415-847-1239; online at washedashore.org, or facebook.com/WashedAshore/

Sculptor and founder of The Washed Ashore Project, Angela Haseltine Pozzi, poses with Cosmo the Puffin, one of her creations made entirely from plastics discarded into the ocean and washed up on distant shores.