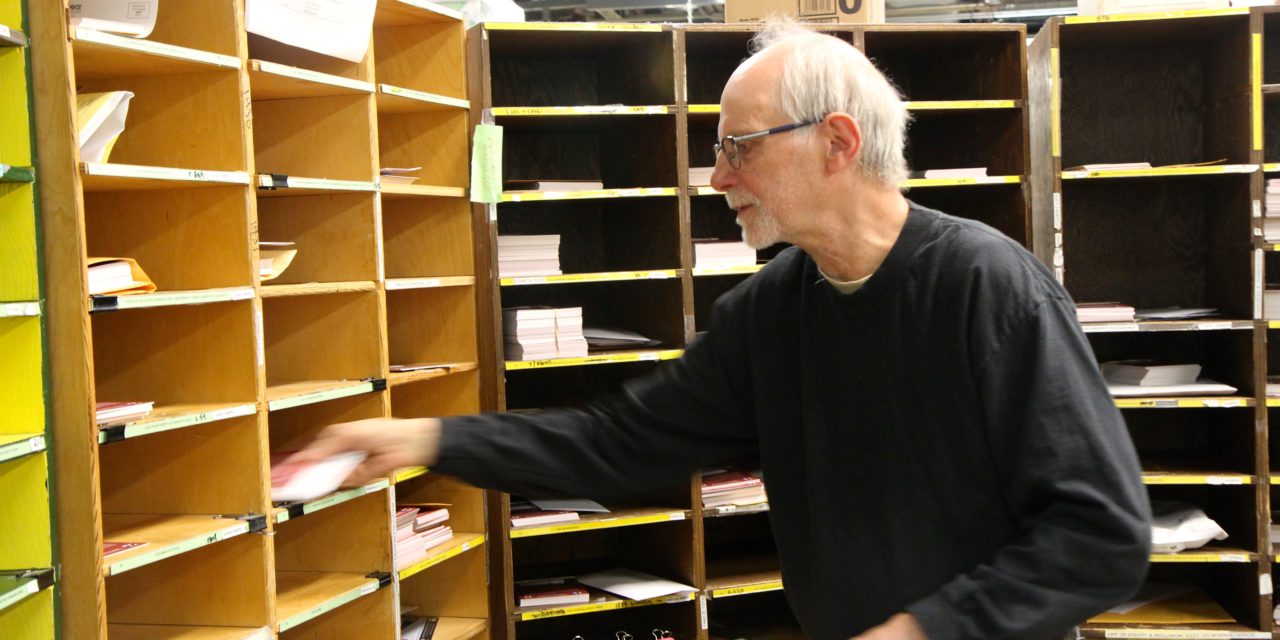

(Above: When he’s not reading scripts, Bill Reid is reading addresses for his job as a mail deliverer for the University of Oregon)

By Randi Bjornstad

By day, he’s an unassuming postal clerk, sorting or delivering mail for the University of Oregon’s mail center in downtown Eugene.

By night, he often puts on a new persona and takes to various stages around the Eugene-Springfield area. Is he a guy who thinks he sees a giant rabbit? Is he a hard-bitten cowboy who nonetheless gets sentimental over Christmas?

Sometimes. But underneath it all, he’s always Bill Reid.

Reid, 68, was born in Buffalo, N.Y., but grew up in Syracuse, N.Y., where he first got into drama in high school.

“I was a senior, and when I went to register for classes, they said I could take an elective now, and I said, ‘What’s an elective?’ “ Reid recalled. “They said there were only two choices left, journalism and drama. I asked if journalism meant a lot of writing, and when they said yes, I said I would try drama — and I got into the first play I tried out for.”

The play was Cheaper By the Dozen, a comedy about a family with 12 kids, and he got the role of Frank Jr., one of the two oldest offspring in the family.

“Last time I moved, I found my old script, and I wondered if it was still as funny as I thought it was in high school,” Reid said. “I read it — and it was.”

That was his first foray into acting, and he was hooked.

“I didn’t have any exposure to it before,” he said. “But I always had been a good reader, and in sixth grade I was asked to read to first graders, so that was a bit like acting. And I do remember that my younger sister and I used to sit around and pretend to do commercials.”

When he did take the stage in Cheaper By the Dozen, he remembers his proud little sister calling out proudly during the performance, “That’s my big brother!”

After high school, Reid headed for State University of New York in Plattsburg, where he graduated in theater, “not a very useful degree.” He came to the University of Oregon for graduate school, earning a master of fine arts in theater, specializing in acting and directing.

While at Syracuse, which he calls “one of the best drama departments anywhere,” Reid was last for a play called La Ronde, written by playwright Arthur Schnitzler.

“It’s a script about love, starting with a soldier and a prostitute, then about the prostitute and a count, then around and around until it comes back to the soldier,” he recalled. “It’s an awful play, so badly written, just awful.”

Years later, in a different theater, a technical director sent Reid and another cast member up to the properties area to straighten it up, and he saw a beautiful chaise longue.

“I said, ‘What play did that come from?’ and she said, ‘One of the worst plays ever.” I said, ‘What was that?’ and she said, ‘La Ronde.’ “

He’s been in more than 100 plays, Reid estimated. By the time he was in his 40s, he made a living working in theater, but that ended in the late 1980s.

“Once you get older, the roles start to disappear, and pretty soon it seems like you’re out of work all the time,” he said. “Then you have to start with the night jobs and the part-time temporary jobs to try to make a living. It’s a rough life, it really is.”

But the memories are legion.

At the Lord Leebrick Theatre, now Oregon Contemporary Theatre, Reid played in Escape From Happiness in the 1990s, a relatively little known play by Canadian writer George Walker, “and it is one of the funniest plays I have ever been in.”

“In the first read-through, we had to stop three times because we were laughing so hard that we had tears running down our cheeks,” he recalled. “That show was sold out all the time.”

He’s had all kinds of roles during his career, “but I think I’m most successful in comedy,” Reid said. “I guess I have a good sense of humor.”

But he’s also played some more difficult parts, including one in which he had to play a demented person, “and I had to laugh for two minutes straight — that was a challenge.”

“I had to learn how to do it. There are six or seven kinds of laughter — you learn all those things in acting classes — but it’s very difficult when you actually have to do it.”

In addition to acting, Reid has had directing experience, including a several-year stint at South Eugene High School.

“In one of those plays, I had a young actor who had to break down in terms to apologize to his girlfriend,” he remembered. “I had to teach him how to cry — there are techniques like using your diaphragm — and the three of us really got into it. We were sitting around a table one day, all weeping our eyes out. A janitor walked by and said, ‘Is everybody okay?’ ”

One of his most cherished roles was in a summer stock production of the Pulitzer prize-winning play Harvey, where Reid payed Elwood P. Dowd, the man who believed he could see and communicate with a human-sized rabbit.

“There’s not a bad part in that whole play,” he said. “The plot involves a sister who keeps trying to have Elwood committed because of his delusion, and one day a driver finally comes to take him away to a mental hospital for treatment.”

The sister asks the driver to describe the place, and the man tells her that most of the people he picks up are happy, and when he brings them back, they are completely different.

“That scene takes up an entire page of dialogue,” Reid said. “I think it’s the best part of the whole show.”

He’s never forgotten the lessons learned in one college class he took, in which the final exam involved a completely student-directed play — direction, sets, lighting, costumes, stage management — with the faculty doing only the casting, often against type.

“It was fun, but it was a whole lot of effort,” Reid said. “I was not a very sophisticated person, and I was cast to play this really smooth guy who breezes in, sits down, and plays and sings songs at the piano. I could sing, but I had to learn to play the piano. I learned all the chords and then sort of vamped the song between chords. It was really good for self-confidence.”

In the same show, a “really hippie-type girl” who usually dressed in baggy overalls was assigned to the femme fatale part, “and when she came in the first time in this slinky, gold lamé gown, it was ‘Oh, my god’ — she took our breath away,” he said. “That is the proof of drama as a profession — it is an art.”

He doesn’t do much traditional acting these days, which makes Radio Redux, which reproduces classic radio plays on stage — complete with sound effects and live commercials — with theatergoers taking the part of the studio audience.

“As I get older, memorizing lines or monologues has become more difficult,” Reid said. “With Radio Redux, we’re all standing up there at microphones holding our scripts and acting the parts with our voices instead of all the blocking and moving around the stage.

There is one role that would coax him back to theater in any form, though, and that’s the chance to play George Burns, who for decades, cigar in hand, played straight man for his zany wife, Gracie Allen.

“They started in vaudeville and made the transition to TV and radio — they had the chops — and I think I do a pretty good George Burns,” Reid said. “I think I’ll practice up, just in case.”

He’s got the perfect day job to do it. Reid’s current work gig at the UO mail center is delivering inter-campus mail to most of the science buildings, a twice-a-day trek that adds up to about 7 miles of walking.

That’s plenty of time to channel the Burns vibes, just in case his dream role ever comes along.

(This profile also appears on the Radio Redux website, radioreduxusa.comhttp://radioreduxusa.com, courtesy of Randi Bjornstad and eugenescene.org)