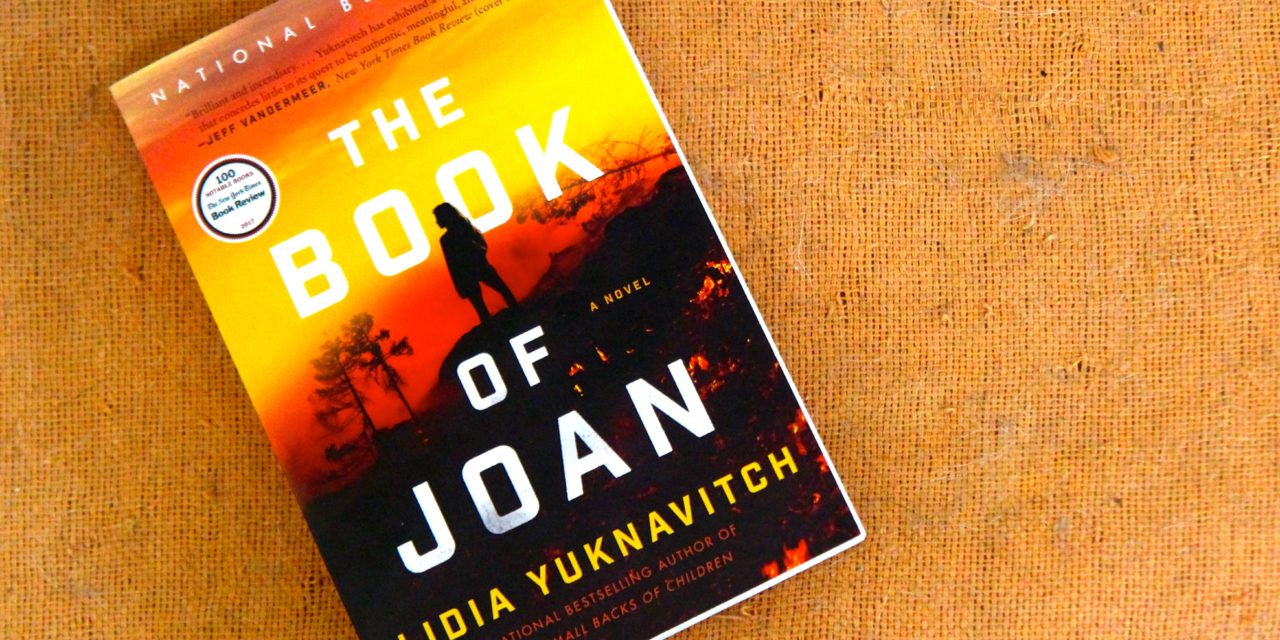

Title: The Book of Joan

Author: Lidia Yuknavitch

Publisher: HarperCollins, New York, NY

Details: A novel, published 2017

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-484-3777); and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

“Herein is the recorded history of Christine Pizan, second daughter of Raphael and Risolda Pizan.”

Literary reviewer Daniel Buckwalter calls The Book of Joan, “the best novel I’ve read in quite some time;” photo by Randi Bjornstad

And we’re off into Lidia Yuknavitch’s novel, The Book of Joan, which was published last year. The Portland-based writer, author of The Small Backs of Children and other novels, has done a fabulous job of lifting the story of Joan of Arc and creating a deep, dark, futuristic tale of resonance as all life and laws and morals on Earth careen first into mayhem, then oblivion.

The year is 2049. Man has been in continuous, global warfare for years. Earth is a radioactive wasteland. Nuclear drones have flown; battles have broken out everywhere in the world. Other geo-cataclysms have made Earth barren.

“It looks smudged and sepia,” Christine says.

Water wars then break out. Class wars break out. Children are kidnapped, enslaved and become warriors themselves. The rich abandon Earth by various means, to CIEL, leaving the rest to fight like feral animals among themselves.

“The meek really did inherit the Earth,” Christine muses, “and the wealthy suck at it like a tit.”

Devolution.

A new race – a purer race, if you will – is being monstrously created by biosynthetics and overseen by Jean de Men, Earth’s last dictator. He’s resides on CIEL, a suborbital complex that sucks what precious life remains on Earth to supply his followers, and his prisoners.

“The name of things,” Christine notes. “They betray our stupidity. CIEL, on Earth, was the name for an international environmental organization, but also for a young person’s video game before the wars, before the great geological cataclysm. I remember. Now it’s what we call our floating world. What lame gods we’ve made.”

Christine has been on CIEL for years. So long, in fact, that she has to try to recall the outside of the suborbital complex and her younger self, before the experimentation and grafting of Joan of Dirt’s story consumed her life. She is 49 and has only a year to live before she will be killed in some elaborate stagecraft that will entertain the residents of CIEL.

“Now, at forty-nine, I’m aging out, a threat to resources in a finite, closed system,” Christine says.

But she has one more battle. And she has her stories, both verbal and grafted onto her body.

Christine recites how Jean de Men came to power: “His early life as a self-help guru, his astral rise as an author revered by millions worldwide, then overtaking television—that puny propaganda device on Earth—and finally, the seemingly unthinkable, as media became a manifested room in your home, he overtook lives, his performances increasingly more violent in form. His is a journey from opportunistic showman, to worshipped celebrity, to billionaire, to fascistic power monger. What was left? When the wars broke out, his transformation to sadistic military leader came as no surprise.”

She continues: “Jean de Men. Some strange combination of a military dictator and a spiritual charlatan. A war-hungry mounteback. How stupidly we believe in our petty evolutions. Yet another case of something shiny that entertained us and then devoured us. We consume and become exactly what we create. In all times.”

And, of course, there’s Joan of Dirt. Her special powers come to light at the age of 10, though no one (not even her parents) knows what to make of them. She can meld with Earth, its trees and vegetation, and regenerate plant forms. She can even resurrect humans, though for no more than a few hours. She is, as the young character Nyx will note, between human and matter. Nearly indistinguishable. “You are,” Nyx tells Joan, “an engenderine.”

Joan of Dirt has fought the evils of Jean de Men. She has met him at every turn of the road. They know each other well. He has captured her, tried and convicted her. He has condemned her, but Joan of Dirt has escaped with her beloved friend, Leonne. Now each side fights to its revengeful — and all-consuming — core, sometimes with precision, sometimes indiscriminately.

And the legend of Joan of Dirt grows, even if she doesn’t know it. She has been beatified by the subjects of CIEL. Christine has Joan’s entire epic drama, from girlhood to warrior, grafted onto her body. “Her story rises up from my skin as if to answer, flesh to flesh. I close my eyes. When you shut your eyes, the universe is internal. I can feel her story underneath my fingers, burned there, rising from my flesh.”

There is so much to unpack from The Book of Joan, but two things stand out for me. First, how power and revenge devour the soul of war combatants, to the point where one side is indistinguishable from the other. After years of war, neither side may remember what started it in the first place.

Yes, Jean de Men is charismatic evil, beyond redemption with each passing day and barbarous gender experimentation, all in the name of procreation to a purer life form that is his twisted vision. But what of Joan of Dirt? She has the power to regenerate vegetation by melding with Earth. Instead, with fiery rage, she is consumed with destroying Jean de Men. To do that, she feels she has to destroy Earth. She has lost her moral compass, too.

The character Trinculo (a beloved friend of Christine’s) explains. “If she comes awake to it, she has the power to regenerate the entire planet and its relationship to the sun. She can bring the planet she killed back to life … Ah, but destruction and creation have always been separated by a membrane as thin as the skin on a scrotum …”

Which brings me to the second item that stands out. It is shown by the 12-year-old Nyx, who two years earlier watched her parents be killed, and then, with Jean de Men standing next to her, she killed other girls so as to stay alive and become another victim of biosynthetics on CIEL.

Nyx, like Joan of Dirt, is an engenderine, except her gift is that she can travel through time. She is sent by Christine to retrieve Joan and bring her to CIEL after Joan’s beloved comrade, Leonne, is kidnapped by Jean de Men. It is the start of the novel’s climax.

Joan is skeptical. She holds a blade to Nyx’s throat. The young girl stands quietly and firmly. “Death,” Nyx murmurs. “It’s always about death. If there’s a mortal short circuit to humanity’s existence, it’s the obsession with death as an ending. Death? You think death means anything to me? Before you kill me, let me tell you a story.”

Nyx explains how her parents were killed, then shows Joan how her body became deformed at the hands of Jean de Men, then the grafting of Joan of Dirt’s story on her deformed body, an art she learned from Christine.

“When I escaped and joined the resistance it wasn’t for you. Your glory or cause. It was for more than survival. It was for revenge. This body—my body. I am the proof of what happens when power turns its eye toward procreation. I am a monstrosity. But that’s not the worst part. A body is just a body. You know? Something deeper lives within all of us. Do you know what it is?”

Joan of Dirt is spellbound. She knows nothing of the medical atrocities or the grafting of her life story by the creatures, the former humans, on CIEL.

“Love,” Nyx said. “… I loved people before Jean de Men did this to me. I know what love was.”

Joan of Dirt had forgotten.

Joan of Arc (“The Maid of Orleans) is considered a heroine of France for her role during the Lancastrian phase of the Hundred Years’ War. An uneducated peasant from an obscure village, she was declared a national symbol of France in 1803, beatified in 1909 and canonized as a Roman Catholic saint in 1920.

As always with symbols, Joan of Arc has been characterized as a demonic fanatic, a spiritual mystic, naïve, a creator and icon of modern popular nationalism, and an adored heroine. She insisted, even when facing death by fire, that she was guided by voices from God.

Among those who have written about Joan of Arc – and Lidia Yuknavitch makes great use of this in the chief narrator role of Christine Pizan – is the poet Christine de Pizan. Christine de Pizan, Italian by birth, wrote the poem Le Ditie’ de Jeanne d’Arc in 1429. The poet was a prominent moralist and political thinker in France during the late medieval period, and she gained fame as the first woman to become a professional writer in Europe.

The Book of Joan will be seen as a cautionary tale for present day events. It takes no imagination to do so. But Yuknavitch, through the story of Joan of Arc, does an exquisite job of explaining why and how these events develop.

The Book of Joan should be required reading this summer.