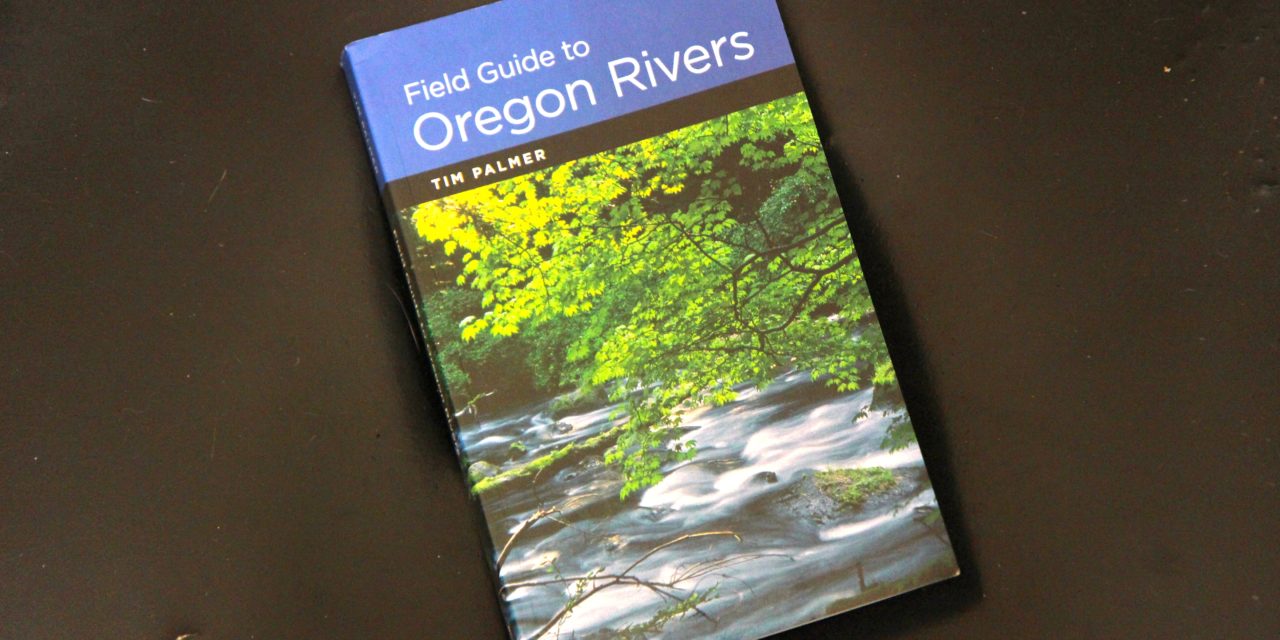

Title: Field Guide to Oregon Rivers

Author: Tim Palmer; sketches by William E. Avery

Publisher: Oregon State University Press

Details: Winner of the National Outdoor Book Award (Outdoor Adventure Gide Books, 2015); winner of the INDIEFAB Adventure Book of the Year (2015); finalist for Oregon Book Award (2015)

Available locally: J Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway, Eugene; 541-342-2002

By Daniel Buckwalter

Oregon’s physical beauty is mesmerizing. Even if you’re a native, or have lived in the state for a generation and believe you have absorbed the splendor, look again. The beauty is never-ending.

And don’t take it for granted, especially the rivers. It’s the rivers, their pathways and lifelines, which support dozens of plant and animal species. And it’s the rivers that two-thirds of Oregonians depend on for drinking water while the rest tap groundwater that is tied to surface flow.

Further – and to highlight how rivers and their ecosystems underpin the economy – the state Department of Fish & Wildlife estimates that Oregon spends $2.5 billion annually on fish and wildlife recreation.

Tim Palmer certainly doesn’t take the state’s 114,500 miles of streams for granted. He’s the author and photographer of Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. He’s written other books on rivers in the Pacific Northwest and throughout the country, and he writes with equal care and knowledge about the rivers in the state he has called home since 2002.

“Imagine the rivers of Oregon loosely resembling spokes of a wheel radiating out from interior regions,” he writes. “The coastal rivers flow west to the ocean. The Willamette, Sandy, Hood, Deschutes John Day, and Umatilla push north to the Columbia. Snake River tributaries flow east to that northbound artery, and southcentral waters trend to land-locked basins in the desert or southward to the California-bound Klamath.”

It’s a handy book to have. “The book might be useful as a field reference to be kept in your pack, dry bag, or glove box for a day, weekend, or vacation,” Palmer writes. “It might become a source of data and tips for recreation, work, or just playful curiosity.”

In Part 1 of the book, Palmer writes about the health of riparian (river-related) plant life (“a key indicator of the health of streams themselves”). He also writes about surrounding wildlife, hydrology (the science of river flow), climate, the natural history of the rivers (geology) and, of course, the fish habitat. This section also includes artist renderings of 50 species of river and riparian plants and animals, drawn by biology professor William E. Avery.

Palmer concludes Part 1 by writing of the problems, protections and restoration of Oregon’s rivers: “The problem for rivers today are water pollution, dams, diversions for water supply and hydroelectric power, floodplain development, invasive species, channelization along with levees and riprap, climate change, and population growth—a fundamental source of many of the other problems.”

Dams, in particular, come under Palmer’s scrutiny. “Pollution degrades rivers, but dams bury them under reservoirs. … Dams halt or restrict the migration of fish, including some of the finest salmon and steelhead runs in the Willamette, Clackamas, Santiam, Metolius, Deschutes, Klamath and Snake Rivers,” he contends. “Below the dams, water is often depleted and temperatures heightened. The new conditions aid alien species, which displace natives. Dams also capture silt and gravel that would otherwise be washed downstream, thus withholding deposits from floodplains on the inside of bends where the sediment would naturally and beneficially accumulate. Degrading or entrenched riverbeds result.”

For all the legitimate problems that Oregon’s rivers face, they have their joys, too, and it is in Part 2 (“River Portraits”) that Field Guide to Oregon Rivers shines.

Starting with the coastal rivers and concluding with the desert streams, Palmer outlines with maps and short histories the hiking, fishing and kayaking opportunities that abound, as well as the easiest access points to particular sections of all the rivers.

“Yet I make no pretenses about running your trip,” he writes. “Unlike some guides, I don’t offer advice about how to run the rapids, I don’t tell you what’s around the next bend in the trail, and I don’t tell you what kind of lures or bait to put on your line. That’s for you to determine, to see, and to do.

“But with recreation in mind (think re-creation), I identify which rivers, and which section of them, are appealing given different interests, skills, and commitments of time.”

Palmer ruefully notes the obvious, that “Writing a guidebook presents a dilemma: some favorite places that I used to have all to myself might become more visited. Yet each of us deserves our share of nature, and without knowing and thereby appreciating it, our commitment to protecting what’s natural and wild will be less.”

So grab a copy of Tim Palmer’s Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. Absorb the mesmerizing beauty of the state’s rivers … and don’t take them for granted.