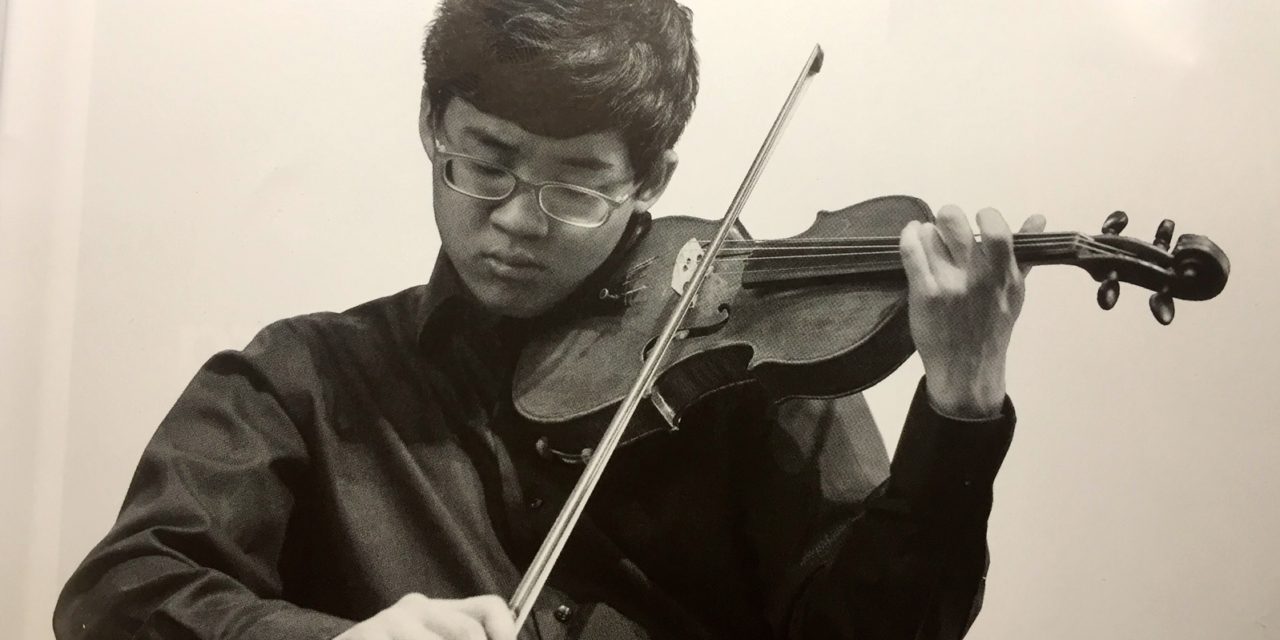

(Above: Photograph of 18-year-old violinist Julian Rhee, as seen in the Eugene Symphony’s 2018-19 program guide)

By Daniel Buckwalter

#commonmanatthesymphony

It started with two musical stories of tortured souls and minds, brilliantly laid out by composers who crept inside the angst and pain of their subjects to profile a pair of geniuses, one a tortured poet with an unforgivable sin in his past and the other a scientist torn between the capabilities of his knowledge and the possibility of using it to destroy the world.

And that was just the first half of Thursday night’s program at the Eugene Symphony on March 21.

The second half of the concert in the Silva Concert Hall in the Hult Center for the Performing Arts displayed hope for the future via the talents of a child prodigy, violinist Julian Rhee. His command and artistry wowed the near-capacity audience that gave him three well-deserved standing ovations.

From the unthinkable to the sublime

Tangled past and bright future abounded in Robert Schumann’s Overture to Manfred, John Adams’ symphony, Doctor Atomic, and Johannes Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D Major. It was a stirring night led by conductor Francesco Lecce-Chong.

The signature piece of the evening was Adams’ symphony. It is taken from the composer’s opera of the same name, which premiered with the San Francisco Opera in October of 2005. Adams later cut the three-hour opera down to create a symphonic version, then edited it again into the 24-minute symphony played in Eugene.

Doctor Atomic follows the great physicist, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and the enormous team he led during World War II in the race to develop the nuclear bomb and test it near Los Alamos, New Mexico, ahead of the Germans. Both opera and symphony take listeners down the troubled path that Oppenheimer and others had to navigate, starting with the first section, The Laboratory, and the abhorrently awesome task at hand.

The second movement, Panic, portrays the primal rush to finish the bomb (“What do the Germans have?”), with the philosophical and spiritual arguments that always boil. They are the same arguments as today, made more stark today by the fact that more countries have numerically more of the same weaponry.

The Eugene Symphony captured all this well Thursday night with the symphony’s apocalyptic start, foreshadowing the Trinity Test (5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945) as well as the bombs dropped in Hiroshima (“Little Boy” on Aug. 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (“Fat Man” on Aug. 9, 1945).

The symphony, composed in three sections echo the clamoring chaos of Los Alamos, a community built almost overnight for this express purpose. Everything is rushed.

Finally, it gets to the third movement (Trinity) and the soul-wrenching cries of Oppenheimer and others, asking, in effect, “What have we done?” Oppenheimer’s doubts, in particular, are brought to chilling life by a trumpet solo played by principal trumpeter Sarah Viens. Later, the scientist attempted to educate the world on what, in fact, were the consequences of this fateful time.

It also brought to mind one of Oppenheimer’s favorite poems, which Adams uses in the opera, Batter my heart, three-person’d God by John Donne ((1572-1631), which is a call to God to take hold and consume man:

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you/ As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend,/ That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend/ Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

These four lines that start the poem illustrate perfectly, I think, the spiritual dilemma Oppenheimer faced as he carried out his formidable task.

But don’t believe for a moment that nuclear weapons are passé and that humankind has evolved, because in today’s world there are eight nations that have nuclear weapons, with upwards of 15,000 among them. Five — United States, Russia, United Kingdom, France, and China —have detonated nuclear weapons. Three more, India and Pakistan with their endless border disputes and North Korea, apparently determined to wield the weapon as a guarantee of its own sovereignty, all have conducted tests nuclear tests. Israel is assumed to have nuclear weapons but refuses to verify it. Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine all had nuclear missiles at one time but transferred them to Russia after the breakup of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Several other countries — Iran, Iraq, Libya, Taiwan, South Africa, Syria, Argentina, Brazil, and South Korea — all have pursued weapons programs at one time or another but for one reason or another eventually shelved them.

Worldwide, the mystique of annihilation is still very real. And accidents can happen.

A breath of fresh air

No wonder, then, that when young Julian Rhee stepped onto the stage after intermission, the audience seemed more than ready to move on, and the young violinist (who studies in Chicago and Aspen, Colorado) seemed happy to comply.

With the red-rimmed glasses that I believe could become his signature, Rhee looks younger than his 18 years. He appeared a bit nervous at first, as if he wished he could blend in with the orchestra. But after the orchestral opening, Rhee comfortably settled into the long, sometimes complicated, and always graceful three-movement Brahms piece.

Rhee swayed with the movements, mastering the artistry of what Brahms is conveying. But he proved more than a master of the technical aspect of the score and instrument. He saw and performed the story. There was character in his interpretation.

The audience deeply appreciated it. One patron, on social media afterward, wondered if we had just seen the next Joshua Bell. I hesitate to go there for the simple reason that Rhee is still only 18, but I wouldn’t be surprised, either, to see his name as a national brand in the years to come.

If that happens, we in the audience Thursday night at Hult Center’s Silva Concert Hall will rightly claim that we were present at the birth of greatness.

Next up

The Eugene Symphony Orchestra continues its season at 7:30 p.m. on April 18 with The Color of Sound, with guest pianist Christopher Taylor. The program includes The Poem of Fire and The Poem of Ecstasy by composer Alexander Scriabin, who believed every musical note has its own specific color. The concept will be interpreted with light and sound by Harmonic Laboratory to music by Claude Debussy (Claire de Lune) and Edvard Grieg (Morning Mood) and, short works by Felix Mendelssohn, George Frideric Handel, Arvo Pärt, and Gunther Schuller.