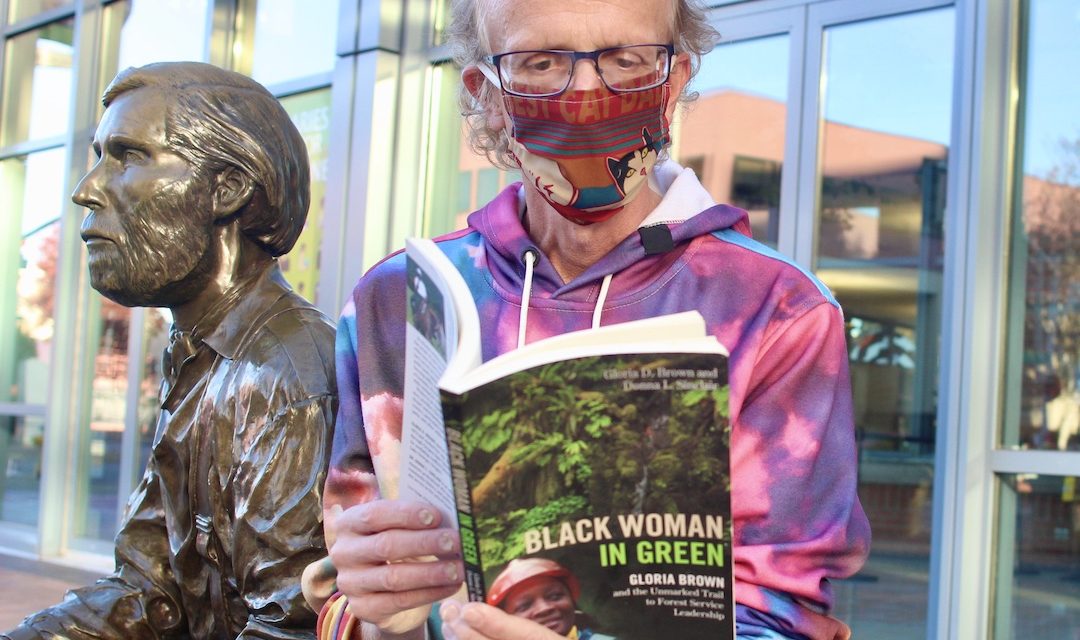

Title: Black Woman in Green: Gloria Brown and the Unmarked Trail to Forest Service Leadership

Authors: Gloria D. Brown with Donna L. Sinclair

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis; 2020

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard St. (541-484-3777); J. Michaels Books, 106 E. Broadway, Eugene (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

The destination is a freeze frame. Its picture is at once glowing yet fuzzy, and it can change shape and form at any moment.

Daniel Buckwalter; photo by Randi Bjornstad

So it is the journey that is life, starting from scratch, collecting the tools that are essential, knowing that you need to be and are better than your current station in life, and building toward that elastic dream.

This is what makes Gloria Brown’s memoir — Black Woman in Green: Gloria Brown and the Unmarked Trail to Forest Leadership — a quick and life-affirming read. She climbed the ranks of the U.S. Forest Service to become, in 1999, the forest supervisor of the Siuslaw National Forest, the first Black woman to manage a national forest in a 40,000-person agency. She later would manage the larger Los Padres National Forest in California in 2004 before retiring. She now lives in Lake Oswego, Ore.

And she got there the hard way.

Brown was robbed of her emotional rock in an instant one night in 1981 when her husband, Willie James Brown, was killed by a drunk driver near the campus of the University of Maryland.

Gloria Brown was in the passenger seat. She had been studying to be a television reporter and later earned a degree in journalism. Now, grieving hard, she was a widow in her early 30s with three kids and little to grab onto.

A native of the Washington, D.C. area, Brown was working as a transcriptionist with the U.S. Forest Service in D.C. She started in 1974, and after Willie’s death, she held tight to the agency as her salvation.

Near the end of the 1980s, Brown started volunteering for other mundane duties and eavesdropping on conversations with Oregon politicians such as Mark Hatfield and Peter DeFazio about forest management in the far-away Pacific Northwest, learning and growing along the way.

It was a healthy ambition of Brown’s to see a wider and taller stage for herself, though she admits to Donna Sinclair, an adjunct professor of history who interviewed Brown for this oral history: “It was all about the money in those days, to feed those kids.”

Soon, though, ambition would intersect with immersion and connect with calling.

“My career did not resemble a typical birth into the Forest Service,” Brown tells Sinclair. “I think of it as a breech birth: I jumped into the Forest Service backward, feet first instead of head first.“

In 1986, Brown took a post in Missoula, Montana, Region 1 of the U.S. Forest Service. She was privileged, I think, to drive to her new start with her children and a friend, to see the vastness of America from the ground up, to not have it be invisible from the air, and to become aware, as she notes, of “a far whiter America than I’d seen before.”

She and family would leave Missoula after a racially tinged incident revolving around one of the kids.

From there, it was on to Oregon, Region 6 of the U.S. Forest Service, where she worked throughout the state, including Eugene and eastern Oregon. Brown qualified as a forester at Oregon State University, then landed her “dream job” on the Siuslaw National Forest.

If Brown’s career trajectory was unorthodox, her life experiences — from a troubled childhood to a rape, to the loss of Willie, to being a single parent of three kids away from her nerve center in Washington, D.C. — served her well to navigate the historical racism and male domain that was the U.S. Forest Service. (In 2007, Abigail Kimbell was named the first female chief of the agency.)

This includes, too, the ongoing battle between environmentalists and timber executives as well as tension between older and younger agency employees, all of which Brown inherited and helped successfully mediate at the Siuslaw National Forest.

As Laurie Mercier, history professor at Washington State University, writes in the foreword: “(Brown]) faced controversies among various public interest groups and within the agency. New environmental ethics often put younger ‘ologists’ in conflict with senior career employees over managing ecosystems and tree harvests, and environmental activists and timber communities became more impassioned about saving endangered species or timber jobs.”

Sinclair does a wonderful job of capturing the rich matter-of-factness and humor in Brown’s oral recounting. I could feel Brown’s relaxed attitude, her looking with justifiable pride at her accomplishments and growth.

Black Woman in Green is worth the read for all of that and more.