(Above: A boy plays in a plaza in Havana, Cuba, in a street scene photographed by Susie Morrill. Below: Morrill with Samson, one of the 20 horses she keeps on her Lorane farm and rides during endurance events; photo by Paul Carter)

By Paul Carter

If an internet image search is any indication, busloads of American photographers prowled the streets of Old Havana during the recent thaw in diplomatic relations with Cuba. In a way, the Communist island nation became a theme park for travelers draped with Canons and Nikons.

And then, in stepped Trump. In his fervor to stop all things Obama, he halted the rapprochement.

It is still possible for Americans to travel to Cuba, and the photos coming back are still mostly the same. Cuba is all postcard images: endless snaps of 1950s vintage Detroit cars, crumbling colonial architecture and saturated colors.

Some photographers, though, look beyond the obvious. Some want to connect with the Cuban people rather than old Chevys and Buicks. One of them is Susie Morrill.

The former Lane Community College photography instructor has traveled to Cuba three times —the last visit a year ago — to document ordinary folk dealing with the realities of life in an impoverished paradise.

Morrill introduces us to people who could be our neighbors down the street, not enemies 90 miles off Key West. She looks her subjects in the eye and they gaze back, unguarded. They open themselves to her direct, compassionate approach. The images she makes are rendered in warm-toned black and white prints, and filled edge to edge with revealing details. I have no way of proving it, but I think these are the photographs that Cubans would want to see of themselves.

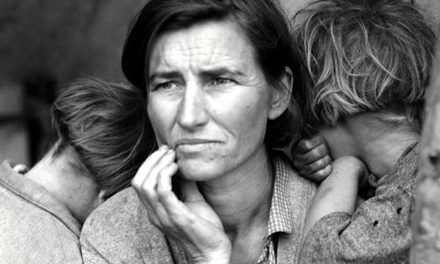

The reason she makes pictures that demand attention, I think, is that she went to Cuba with a self-assigned project. She set out to interview people — senior citizens, in particular — about the Cuban health care system. She went as a documentarian in the tradition of the great depression-era Farm Security Administration photographers, such as Dorothea Lange, that she so admires.

Morrill does not shoot and run. She takes time interacting with her subjects. She describes her style as “confrontational realism” and her goal is to expose the humanity in people — the humanity we all share. The reality of Cuban life, she says, is pervasive poverty. The average Cuban lives on $18 per month and for seniors, the amount is a $10 monthly government stipend.

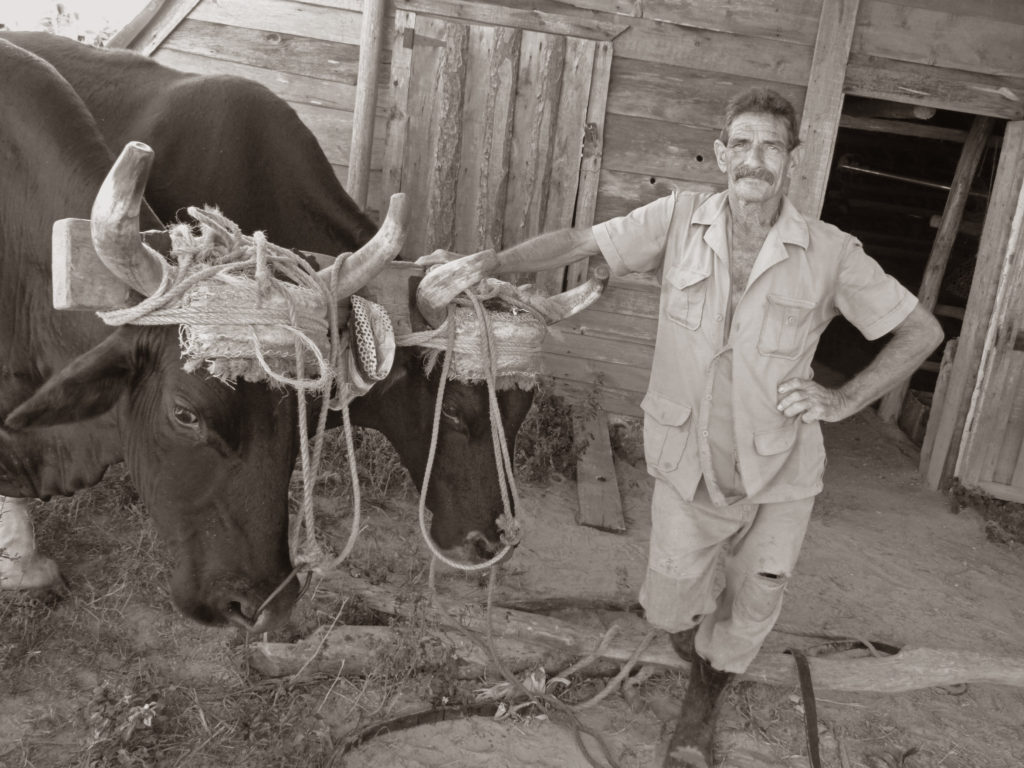

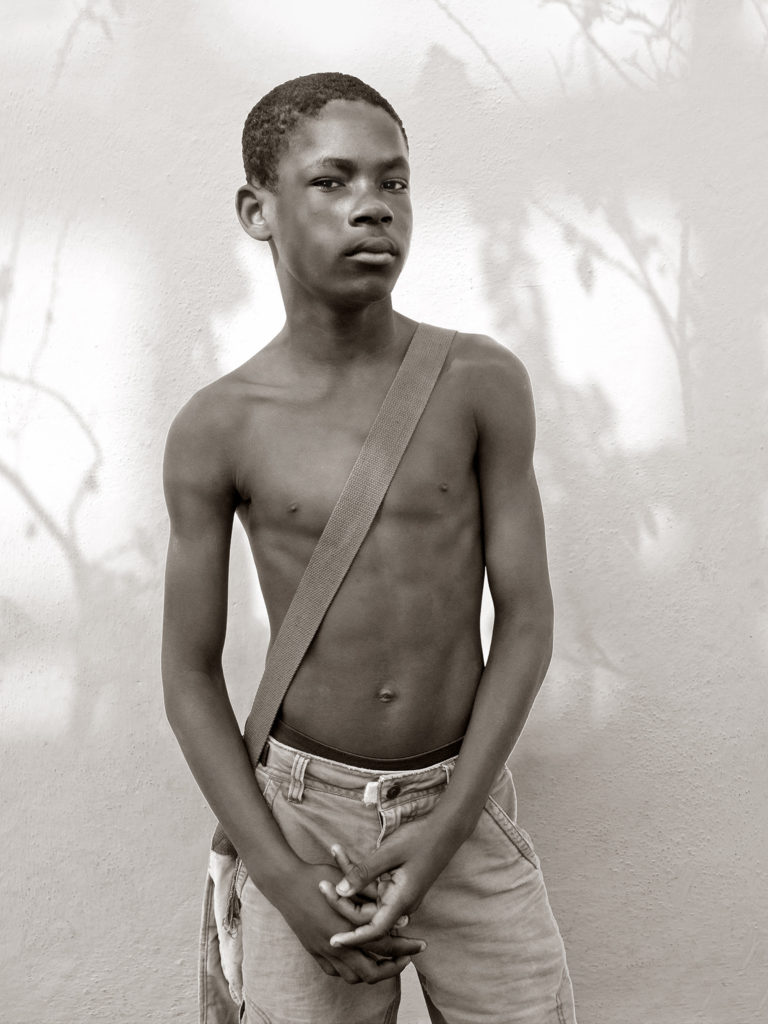

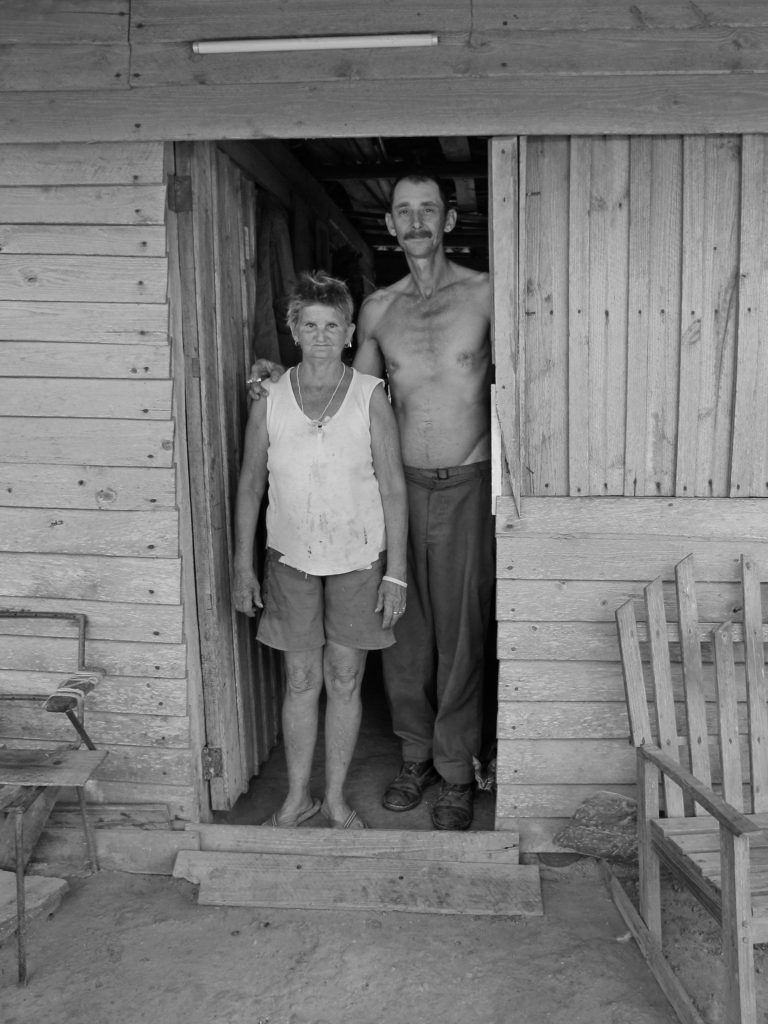

And yet, the Cubans she meets are stoic and dignified in their demeanor. A farmer stands with one hand casually on the yoke of his team of oxen. A teenage boy stares proudly at the camera and holds a baseball bat. Is he dreaming that he might follow Yasiel Puig to the L.A. Dodgers? A campesino and his wife stand in the doorway of their home; the picture recalls a Depression-era image by Walker Evans.

Morrill’s pictures are a transaction, and she keeps her side of the bargain. In some cases, she left her subjects with small daily necessities such as tooth paste or aspirin. She gave gifts of school and art supplies to children.

And when she visited rural families, she treated their pets for intestinal roundworms. Roundworms? This is not what tourists do. The source of Morrill’s veterinary interest is that she is serious about animal welfare. She keeps 20 horses and 20 purebred dogs on her 23-acre farm in the hills near the rural Oregon community of Lorane.

Morrill is self-possessed and sinewy, toughened by hours in the saddle. Those hours were accumulated over years as a competitive long distance cross-country rider. She has raced in endurance events that test horse and rider over courses covering 50, 75, and 100 miles in one day. She’s been doing it for 25 years and in 1998 was selected for the 12-member U.S. Equestrian Team. She estimates that she has ridden 10,000 miles in competition. In an aside, she says that long training rides are an opportunity for meditation. Those hours afforded her time to think about photo projects.

Preparation for her career includes BFA and MFA degrees at the University of Oregon. A significant influence was her 10 years as an assistant at the Ansel Adams Workshops in Yosemite. She rubbed shoulders with luminaries such as Ruth Bernhard, Ernst Haas, John Sexton, and Sally Mann.

Today, at 58, Morrill concentrates on the daily chores at Midnight Sky Farm as well as tending to her photography. So far, she has printed 60 photographs from her Cuba project and has had shows at several area galleries; she also contemplates collecting them in a book. She also has plans for a book of her photographs in the American West. And, just for fun, she is a big fan of Instagram.

One more thing: Morrill also devotes time to Photography at Oregon, the non-profit group that promotes fine art photography in Oregon. She has chaired the organization since 1985. It sponsors exhibits, lectures, workshops, and an annual art auction.

PAO began as a small gallery within the University of Oregon Art Museum; it celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2016 and has the distinction of having created the first gallery on the west coast dedicated solely to photography as art. The next event hosted by the group is a visit by Portland artist Grace Weston. She will show photographs of her dioramas at the Dot Dotson Photo Gallery, beginning on Dec. 14. Weston describes her work as “narrative staged imagery with a psychological twist.”

(Below: A gallery of photographs taken by photographer Susie Morrill during her trips to Cuba)

Photographer Susie Morrill visited Cuba in 2017 determined to meet rural people such as this farmer with a team of oxen.

A bride who was in the midst of her photography session on the street blew a kiss for Morrill’s camera.

Young girls pose for the American photographer.

A Cuban portrait photographer manipulates his primitive wooden camera while his subjects wait.

A boy poses warily for Morrill.

Elderly men were found as they enjoyed conversation on the street. They improvised some makeshift seating.

Boys pose happily for the American.

A farming couple stand for a portrait in an image reminiscent of a photograph from the depression years in rural America.

A teenager with a baseball bat is testimony to the power of the American game in Cuba.

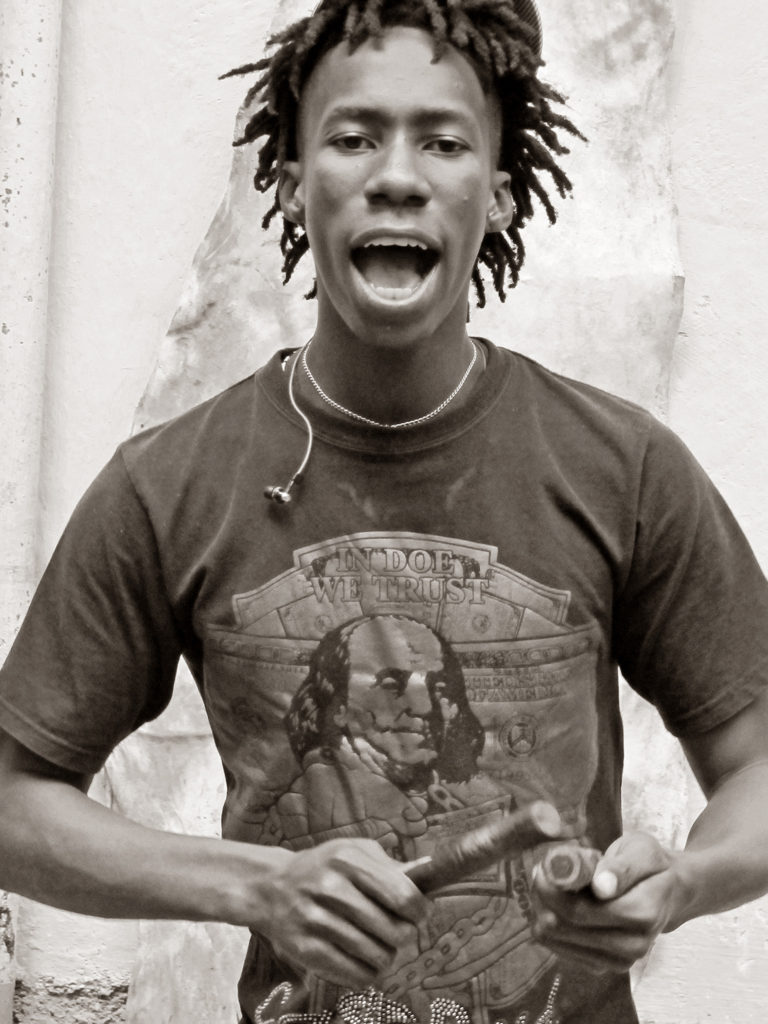

A young Cuban street musician performs, part of a rich musical culture enriched by west African and European influences.

fantastic

Awesome Pictures Susie!

What an amazing and beautiful look at the people of Cuba by a talented and sensitive photographer.

Sent from Addison, Vermont Dec . 29, 2018