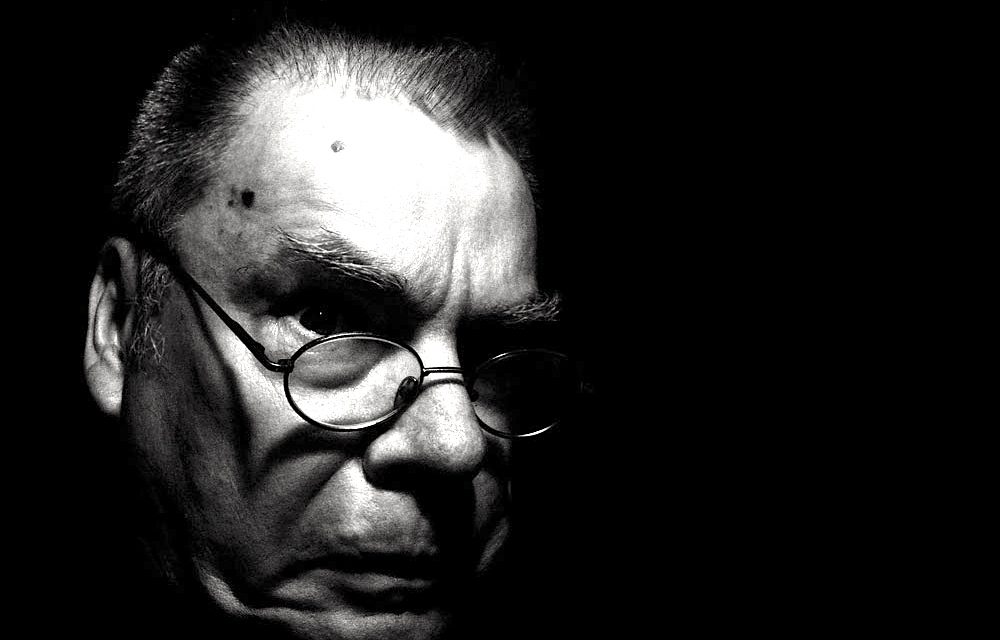

(Above: A portrait of C.A. Burns by C.A. Burns; in what may be a clue to his reclusiveness and reluctance to share his work C.A.Burns calls this self-portrait, “The Gatekeeper”)

By Paul Carter

Chances are very good that you have never seen a photograph by C. A. Burns.

“Shadows and Light” is one of C.A. Burns character studies in black and white

And, though there are a few images reproduced here, it’s likely you will never stand before one of his large and mesmerizing black-and-white prints. Only a few others besides his printer and framer ever see the man’s work.

That’s sad. Because this is a photographer whose standards are extremely high. His standards for bringing the work to an audience are yet higher.

The work is worthy of attention and . . . waiting. It sits, meticulously printed, framed, and wrapped in brown paper, in his apartment. He used to display a few pictures in his home, but tired of that. Now they are almost all tightly wrapped, just as they came from the frame shop.

If the artist ever does show his work, the gallery space will have to be big. His prints are oversized, up to 24 inches by 36 inches. A good image becomes “outrageously good” when printed at the largest sizes his 35mm negatives will allow, he said.

Burns, who lives in Eugene, labors in self-imposed obscurity.

Many serious photographers never formally show their work. Either they don’t want to or can’t afford it. It’s expensive, after all, to mount a gallery exhibition of framed, fine-art prints. And why go to all that trouble? Today there is the internet to give photographers at any level a way to find an audience.

All sorts of characters piqued Burns’ interest, including a colorful character he dubbed “Pin Lizard Lady”

For Burns, though, the issue is much more complex.

Though he is no Luddite, he is wary of the world wide web. The theft of images is too commonplace for Burns to accept the risk. A gallery show? Well, that’s tricky. It depends on many intersecting factors: the adequacy of the gallery space itself; his trepidation with an

audience he does not know; and now, the fact of his declining health.

Burns is an earnest and cerebral man with piercing blue eyes. Once vigorous, he moves slowly these days. At 70, his life is held hostage by kidney disease and dialysis. “There’s always something going wrong with my body,” he said in a recent interview. The malaise that shadows him even makes carrying a camera difficult.

If he has an internal struggle with his art; it may have started with the way he fell into photography.

It is unusual in a school for religious studies to seek a world view through the tool of the 35 mm camera. But it happened for Burns in a classroom at Garrett Theological Seminary at Northwestern University.

He was 30 years old when he studied at the Methodist school for a year. In the seminar called Media Theology, Professor Paul Hessert demanded that his students “do theology with a camera.”

Assignments and critiques required Burns and his fellow seminarians to approach existential questions through the pictures they made. The Bible was “always a backdrop” to the class. “I just had questions,” he said of his attraction to religious studies.

Hessert expected the 10 students in the class to “get what’s inside of you out into the world.” Through rigorous discussion, the professor encouraged a contemplative mindset about the execution and meaning of images. “It was the best thing that could have happened to me in

photography,” Burns said. “The standard was set so high, so early.”

Although time spent in a seminary did not result in a religious vocation, Burns was deeply affected by it. He calls this portrait, “Madonna”

Seminary did not lead to a theological career, but did convince Burns to devote himself to a spiritual pursuit of photography.

To make a living, he started a career in social work, managing a training center for developmentally disabled adults in California. After several agency positions, the path ended in burnout. Odd jobs followed in San Francisco and briefly in Seattle. He started a professional darkroom and photography business. There were even episodes of living on the street forced by his precarious financial situation and a natural disaster, a mudslide in San Carlos, Calif. in 1983.

In Eugene since 1991, Burns taught photography at the Craft Center at the University of Oregon and worked for Dot Dotson’s photo equipment and photo finishing stores.

Along the way, there was plenty of artistic rejection. A gallery owner in San Francisco turned down his early work with the advice to “print bigger.” He took that advice to heart.

A chance to show his portfolio to Ruth Bernhard, the fine art photography luminary, elicited the advice to “get yourself a book.” There has not been a book. He has applied for, but has never been accepted, for a newspaper photo job.

Burns’ photography defies easy categorization. He works in single images that range from street portraits, still life and landscapes to documentary photographs. He also has experimented with manipulated images. There is some color; all the work is 35 mm and done with natural light.

He is drawn to faces but hastens to explain that he wants to photograph people — often strangers on the street — to reveal “what the person is about.” Portraits almost always involve hours of

conversation with his subjects. He is never a snapshooter.

Burns did not always express his portraits in the form of faces; in this photograph, called “Street Hands,” he portrays the essence of life as experienced by those living on the edge of society

He has also used photography to explore family relationships. A closeup of his father’s hand, contorted by arthritis, is a reminder of the difficult relationship he had with his father. “I saw the image for years before taking it,” he said.

Whatever he photographs, he responds most carefully to his internal muse. “If it didn’t stir the muse in me, I did not care.”

He is dismissive of photo contests, a popular path to renown. “It’s an art, not track and field,” he said.

Over several hours of interviews, Burns returned again and again to the deeply personal nature of his work. It’s “like keeping a diary,” he said. His pictures are “the visual diary of my life.” And, he adds, “All photographs are autobiographical.”

Burns showed a few photographs during an association 20 years ago with PhotoZone, the Eugene fine art photography collective. The experience was a “let down.” He was dismayed by the lack of critique of his work.

However, the question remains: Will the breadth and depth of his work be brought to any audience? It seems unlikely, given his opinion of casual gallery goers. He abhors the idea of strangers walking by his work, pausing a moment or two and moving on to the next image. For all the effort, he said, “there’s no return.” And, I think, he means a spiritual, not remunerative return.

I am reminded of the reclusive Chicago street photographer, Vivian Maier. She worked for decades in complete anonymity. Some of her negatives were discovered quite by accident a few years before her death in 2009. Since then, through the internet and the efforts of several persistent admirers, her work has received critical acclaim.

Thanks to those who stumbled on her pictures, she found an audience.

Recommended reading: “Discover Yourself through Photography” by Ralph Hattersley. It’s a text that was required in the seminary class that changed Burns life, and which he said is still relevant today.

A picture of Snow Geese is one taken during his student years that particularly pleases C.A Burns

I had suggested to CA that he rent a storage box for his photos with the rent prepaid for a number of years, so that at some future time, his photos will be discovered ala Vivian Maier.

Charles A. Burns died on March 19th, 2019. He was 71 years old.