By Paul Carter

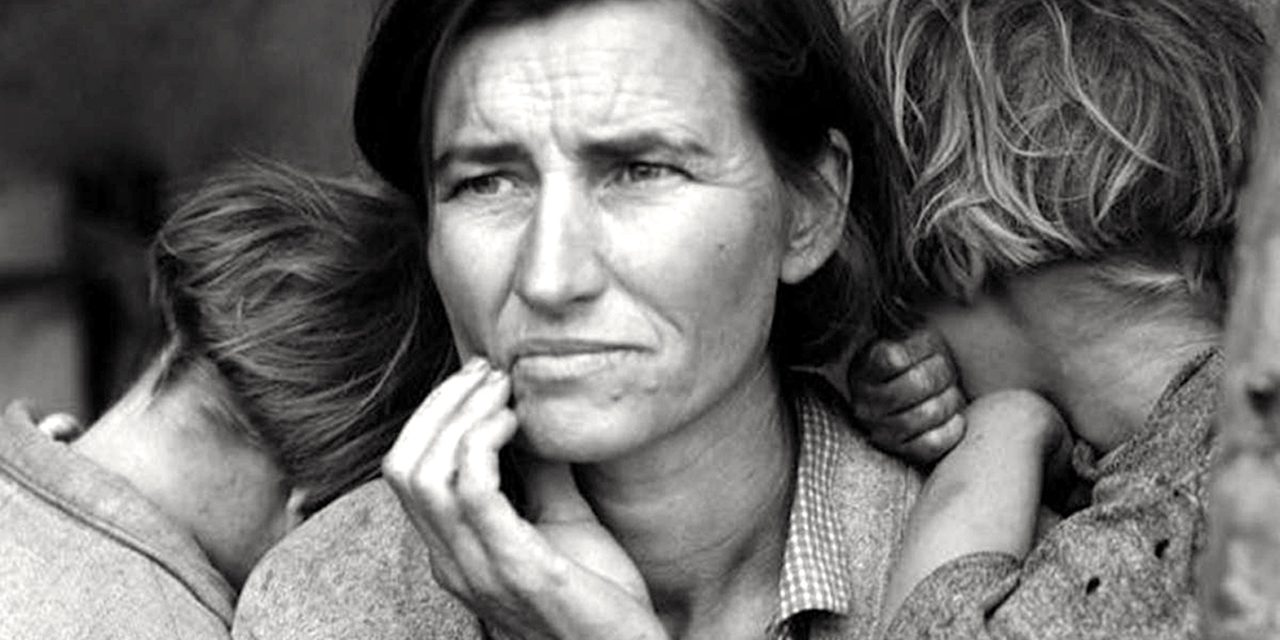

Migrant Mother. In the history of photography, it has come to mean only one picture.

A 32-year-old woman, Florence Owens Thompson, sits in the opening of a rough canvas shelter. She does not look at the lens; she stares to some place in the distance. Her face is lined beyond her years; stoop labor in farm fields has hardened her beauty. She looks worried . . . and indomitable. Two little girls frame her figure, hiding their faces behind their mother’s shoulders. Thompson’s holds an infant in her lap.

It’s late afternoon on March 6, 1936, a rainy day in the depth of the Depression when the photographer takes us to that migrant labor camp in Nipomo, California.

Though I have studied thousands of photographs taken during the Depression by the photographers hired by the Federal government’s Resettlement Administration— later the Farm Security Administration — this is the one that I always remember first. For many of us, it is the image that defines the Depression. The word “iconic” is overused these days, but for this picture, the word is right.

In about 10 minutes and six exposures with a 4X5 Graflex camera, Dorothea Lange made this portrait. In that press of the shutter, she forever humanized the Great Depression.

And this picture might not have been made.

In Lange’s telling, she was driving home after 30 days on the road, photographing migrant farm workers when she noticed a small sign at the edge of Highway 101: Pea-Pickers Camp. It was raining. She was tired and wanted to get home to her own children, so she drove on past. For 20 more miles she debated what might be found in that camp. Finally, her instincts compelled her to turn around and drive back.

Pulling into the camp, she noticed the woman and children under the lean-to shelter. She approached and simply explained that she was “from the government.” She asked permission to photograph and made her first exposure. Now actively posing her subjects, Lange began refining the portrait. She moved closer with each frame. She worked quickly and made four more pictures. Then she must have asked Thompson’s two young daughters to turn their faces away from the camera. She may have asked the mother to bring her right hand to her face. She made the final exposure. Lange sensed that she had something important — an image that surpassed anything she had shot in the previous month.

The desperation etched on Florence Thompson’s face became the focal point of Lange’s composition. Every element of that photograph focuses attention on her face and worried eyes. The lives of two women briefly intersected, and history was made in great documentary photography. Indeed, it was also art.

The picture was published widely and provoked an outpouring of citizen and government compassion for the workers in the Nipomo camp. Ironically, Thompson and her family already had left the camp by the time food relief arrived.

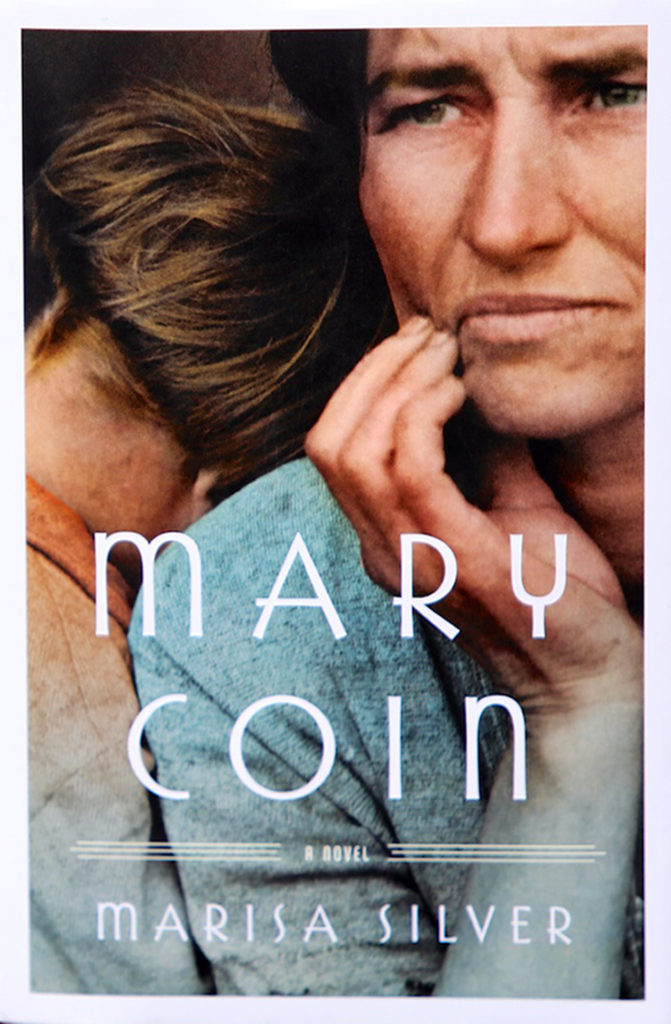

Writings about that chance meeting in 1936 is abundant. There are books, essays, scholarly treatises, and dozens of web references. And there is fiction as well, in the form of a 2013 book by Marisa Silver, Mary Coin: A Novel. This is prose that reimagines the confluence of lives that led up to Migrant Mother and then what could have come after.

The novel creates the fictional lives of the photographer Vera Dare and Oklahoma Dustbowl refugee Mary Coin and her husband and children. There is a third character as well, Walker Dodge, a college professor whose grandfather has a surprising role to play in the lives of the two women at the center of the story.

The story unfolds by introducing each character in turn, and we learn how each lives with adversity. In the present, Prof. Dodge is just splitting up with his wife and trying to cope with a rebellious teenage daughter.

In the most satisfying chapters, we go back to the 1920s and ’30s to meet Mary Coin in Oklahoma during her marriage to her first husband, Toby, and see the hardscrabble life that drives them west. In the central valley of California they are paid pennies a day to pick cotton, fruit, and vegetables. They move with the harvests, packing their few belongings in a beat-up old Hudson, then driving to the next migrant camp.

After years and several marriages, Mary has seven children and still lives in excruciating poverty, sometimes dragging her cotton-harvesting sack behind her with her newest baby in the bag. Always fearing she might lose her job, she keeps working through pain and thirst, watching other pickers faint in the heat. The water wagon at the end of the row is the promise of relief that keeps her going.

This is a story impossible to imagine by simply viewing Lange’s picture. Silver creates plausible portraits of her characters based on well-documented facts about the “Dirty Thirties,” enhanced with her spare, but evocative prose. We need the written word to learn that the woman in the picture has survived in the Nipomo camp, feeding her family on peas stolen out of the fields and birds trapped by her children.

Finally, there is the story of Vera Dare, the fictional Dorothea Lange. She also is a tough woman who triumphs over a childhood bout with polio and a life of dragging one foot as she limps into an improbable career as a portrait photographer to the wealthy in San Francisco.

But one day in 1933, Dare notices the unemployed men on the sidewalk beneath her studio window. She picks up her camera and heads to the streets to discover that she is meant to be a documentary photographer.

The novel comes full circle back to Vera Dare’s death and the discovery of a letter she wrote to Mary Coin that was never delivered. It also reveals the lifelong resentment Mary Coin felt toward the famous photograph, which portrayed her in a single moment of her life, solely as a woman who existed on the verge of starvation, feeding her deprived children on peas and dead birds.

A final twist in the novel brings Walker Dodge and his family back into the story and will strike many readers as implausible. In fact, given the strength of the compelling story about these two women who could not be defeated, it is unnecessary.

At the same time, this melding of the historical photograph and the novel written around it is a particularly satisfying combination.