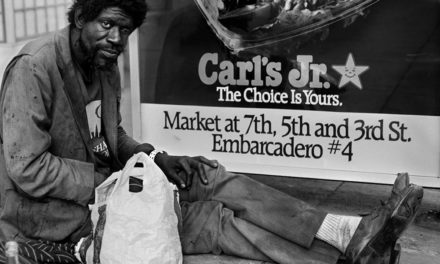

Above: Longtime Eugene-area photographer John Bauguess; photo by Paul Carter

By Paul Carter

The demolition of Hayward Field is underway. It’s an event that will attract gawkers and now, in 2018, many will pull out their smartphones to record the event for social media. Professional photographers will show up too. There will be no dearth of images, particularly as the historic wooden east grandstand is taken apart.

An older man with a camera may be in the crowd. He’s a bit rumpled and moves slowly these days, but I will want to see his images. That’s because he knows a thing or two about this community’s penchant for abandoning its history in favor of building the shiny and new.

Besides his fascination for the changing Eugene scene during its urban renewal years, Bauguess also focused on ordinary life in Oregon’s rural areas

The photographer is John Bauguess. He’s a documentary and journalist shooter who has quietly worked the streets of Eugene and other Willamette Valley towns for more than 40 years. He set the tone for much of his career work when he documented the rush to urban renewal in Eugene in the 1970s.

Go into Voodoo Doughnuts downtown around the corner from Kesey Square, and there is artwork on the walls that suggests some local history. What is missing is a Bauguess photograph of Pope’s Ice Cream and Donut Shop.

If you were in Eugene in the early ’70s, you might have looked in Pope’s shop window and seen Mrs. Pope working at the donut machine, spreading fresh donuts to cool in the front window. It was a small-town American scene straight out of the Great Depression.

The days were numbered for the shop on Willamette Street when Bauguess assigned himself and his photography students at Lane Community College to document the place in still and movie images. The student footage was used for a local-access TV story. Bauguess’s photographs never made it to the printed page; fortunately, they are now archived in the Fine Art Photograph Collections at the University of Oregon. The UO archive has acquired several of his portfolios — altogether some 300 images. Many reveal what Eugene was like before the fervor for urban renewal took hold. There are also portfolios on Latino migrant workers in Woodburn; on old-time fiddlers; and on the social life of Oregon’s small-town Grange halls.

In another of Bauguess’ artistic side streets, his photographs also illustrated the 1978 book, “Of Wolves and Men” by Barry Lopez.

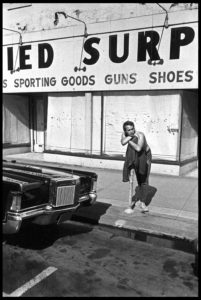

Bauguess captured this image on Willamette Street in front of Allied Surplus, an annex to Archie Weinstein’s main store between Sixth and Seventh avenues. Weinstein later became a colorful and controversial Lane County Commissioner who fought Eugene’s urban renewal plans as the city condemned his property and tore down his buildings. The Hult Center for the Performing Arts now occupies the site.

Bauguess, 74, sensed what he wanted to do with his life when he bought a camera while serving in the Coast Guard Reserve in Seattle. During off duty hours, he wandered the streets of the city snapping pictures. Trying for pictures of people seemed to resonate the most.

Once out of the service, he studied at the UO and at the San Francisco Art Institute. At Oregon in 1961, he was a student of landscape photographer Bernard Freemesser.

After working as a reporter and photographer at the East Oregonian in Pendleton and Klamath Herald and News in Klamath Falls, Bauguess returned to Eugene to teach part time and freelance. It was around 1970 that he began carrying his cameras into the Brass Rail Tavern and making portraits of the regulars. “I liked the social scene there,” he said. “I drank a little beer, but mostly Tab.”

It was in the dark, smoky confines of the Brass Rail that Bauguess began to get close to people with his camera. He looked for the mystery and theatricality — at times absurd — in human behavior. In an ironic black-and-white style reminiscent of photographers like Garry Winogrand, he recorded a social landscape that urban renewal would soon sweep away. The tavern would eventually close in 1972.

In one photograph, a couple sits at a tavern behind pitchers of beer. The woman smiles awkwardly before the camera; the man rolls his eyes, sheepishly perhaps? What are they thinking? Actually, Bauguess knew the couple, Arlo Giles and his wife, Sally. It is a slight, but universal human moment. Everywhere, people while away hours in shadowy pubs, taverns, bars, dives. They drink, smoke, whisper and occasionally a man with a camera appears.

In Eugene, as often as not, that photographer with a Nikon F over his shoulder was John Bauguess.

He didn’t show those downtown photographs until 2000, when they appeared in the Provenance home furnishing store’s Art Grotto. Time and the vagaries of life seemed to have gotten in the way of printing the work. “I had other things to do, like earning a living,” he said.

Over his career, he has had one-man shows at Grand Central Station in New York City, at Blue Sky Gallery in Portland and several galleries in Eugene.

The Grand Central photographs were from his Oregon Old-Time Fiddlers essay in 1979. The black and white images were printed as transparencies and illuminated in individual brass cases two feet by three feet. The exhibit in 1995 was on display four months in the 42nd Street passage to the terminal. It’s possible that more than a million people saw John’s fiddlers.

A retrospective of John’s career work was the subject of a 2010 show at Blue Sky Gallery, the Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts, in 2010. The show, titled Why Not?, drew from his personal and commercial work. There were pictures of luminaries such as Ken Kesey, John Belushi and Sen. Mark Hatfield. But, as always, his ironic, witty style came through most tellingly with his documentary work.

My favorite: A gathering of glee club singers in white tuxedos are entertaining on the steps outside the Hilton Hotel next to the Hult Center. It’s a wide shot and the singers raise their arms together, perhaps in a closing flourish. In that moment, next to them, incongruously, a procession of monks in their cowled habits walk past.

It’s as if the monks came with their own chorus. Terry Gilliam might

have invented the scene for a Monty Python comedy sketch.

Most recently, in 2012, the environmental activist in John Bauguess was the subject of a show at Maude Kerns Art Gallery in Eugene. His documentation of the destruction of Parvin Butte overlooking Dexter was the subject. The collection of large color prints was titled Silent Witness: Parvin Butte Oregon. It documents the gravel mining on the butte that still angers Dexter residents.

He had worked on the pictures for two years. “It’s important to document this,” he told a newspaper reporter. What I want is for people to experience what the people of Dexter are experiencing.”

His last, unfinished project was collecting images that document the Willamette Valley’s past. Bauguess died on Jan. 24, 2020. He was 76.

Beyond the donut shop’s window and its wistful spectators, demolition of downtown buildings progresses during the Eugene’s urban renewal era that spanned 1969-1974. Some business owners blamed the eventual failure of their stores on competition from the recently built Valley River Center. Others hoped that urban renewal would revitalize their small downtown businesses. The empty lot directly across the street had been the site of the Odyssey Coffee House, a popular gathering spot in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Before that, the building had housed the Carroll Drug Store, which opened in Eugene in the late 1920s.