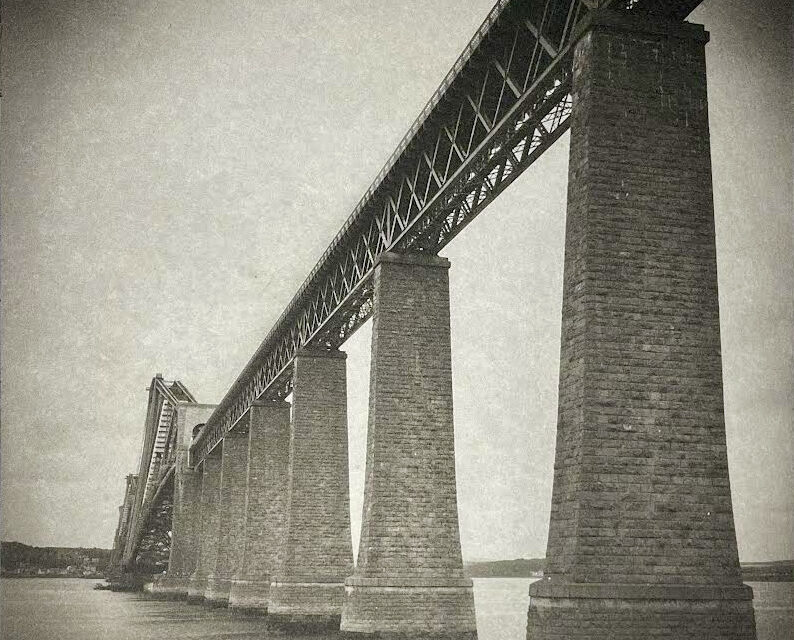

(Above: Forth Bridge, photogravure print by Ray Bidegain, part of an exhibit called A Quiet View at the Don Dexter Gallery in Eugene)

By Randi Bjornstad

The Don Dexter Gallery is showing an exhibit called A Quiet View — photogravure prints by Portland artist Ray Bidegain — through Dec. 29.

If photogravure sounds like something really old, it is. (Remember the lyrics to Irving Berlin’s 1933 song, Easter Bonnet, about the annual Easter Parade in New York city, which include the lines, “On the avenue, Fifth Avenue, the photographers will snap us, And you’ll find that you’re in the rotogravure”?)

But the photographic process is even much older even than that, dating to about 1850. Here’s how the Getty Conservation Institute describes it in its volume, The Atlas of Analytical Signature of Photographic Processes: Photogravure, published in 2013:

The photogravure process (see the print in fig. 1 for an example) has a long history, starting with manual printing techniques and aquatint printing. The roots of the photogravure process can be traced back to William Henry Fox Talbot (1852), who used a “screen” of black crepe for the mechanical translation of tone values on a steel plate coated with a light-sensitive layer of dichromated gelatin. This was the starting point for both the photogravure (the use of dichromategelatin) and halftone processes (the use of a screen). In Talbot’s 1852 method, the steel plate was etched with a solution of platinum chloride to form a printing plate. Talbot changed the process in 1858 by depositing a resinous powder on the surface of the exposed, sensitized, gelatin-coated copper plate. When heated, the resin microparticles bonded to the gelatin layer and facilitatedthe formation of a delicate grain pattern after etching with a solution of ferric chloride. Talbot also introduced consecutive etchings of copper plates using solutions of different concentrations of ferric chloride to improve the tonal scale of the printed images.

It appears incredibly complicated, and photogravure still is held in high esteem not only for its complexity but the quality of its images, made from photographic negatives that have been etched into copper and then printed with ink. The result is deeply dimensional tones of light and shadow, with highlights that often appear both soft and luminous.

In that vein, Portland-based Bidegain’s show is titled A Quiet View and consists of 26 recent editions of his hand-pulled photogravure prints. He has been a fine-arts photographer for more than 20 years, first creating platinum prints from large-format negatives before switching to the photogravure print process about five years ago. He now pursues that technique through his company, Cascabel Press.

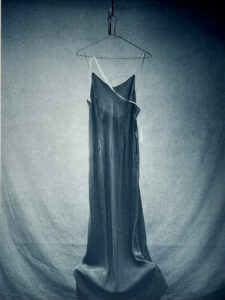

“Indigo Whispers,” a photogravure by Ray Bidegain

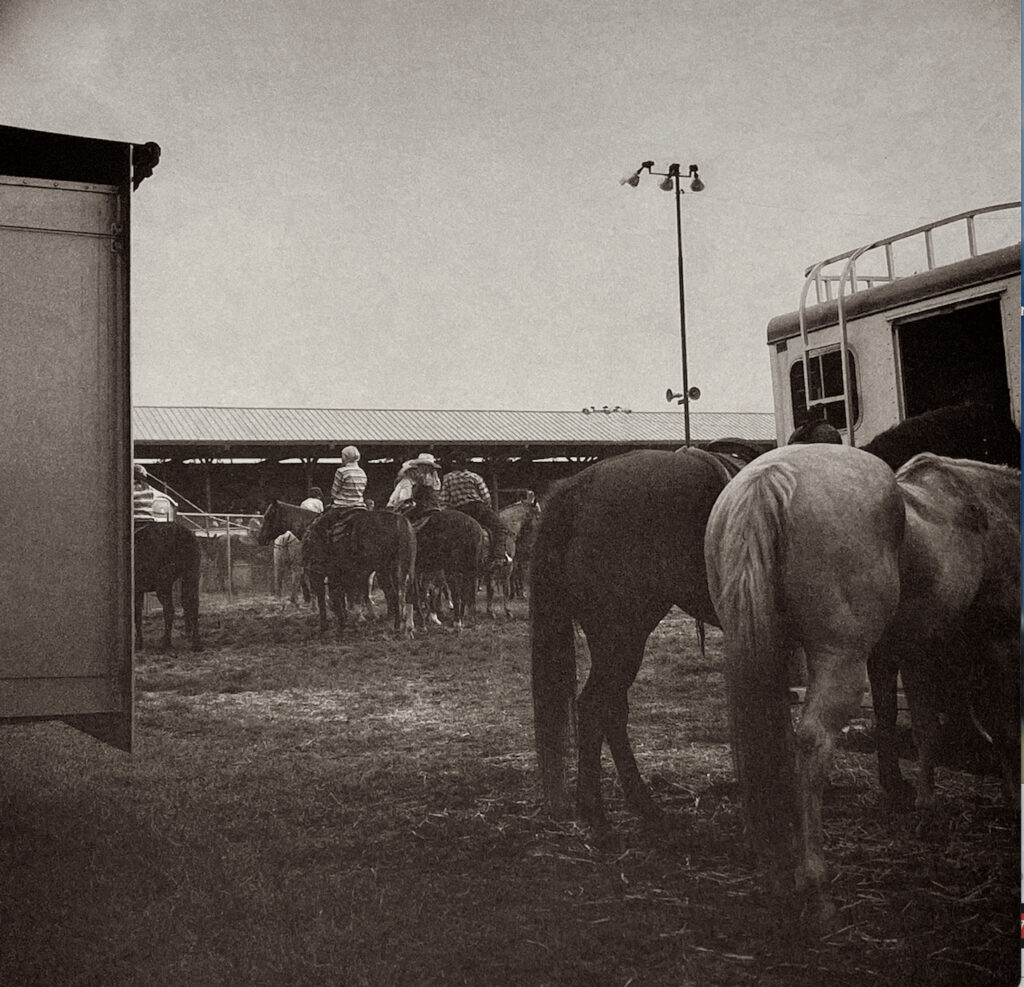

The images in this show range from landscapes from the Columbia Gorge to a woman’s slip dangling from a clothes hanger to a scene of cowboys and their horses waiting to compete at a rodeo.

This exhibit has been selected and sponsored by Photography at Oregon.

Don Dexter Gallery, described by its owner as an “Indigenous-owned gallery,” has existed since 1997, first by way of quarterly exhibits by local photographers shown within Dexter’s dental office on Willamette Street in Eugene, and more recently in its standalone location in Crescent Village in north Eugene.

A Quiet View, an exhibit of photogravure at Don Dexter Gallery

Above: At the Rodeo, photogravure print by Ray Bidegain