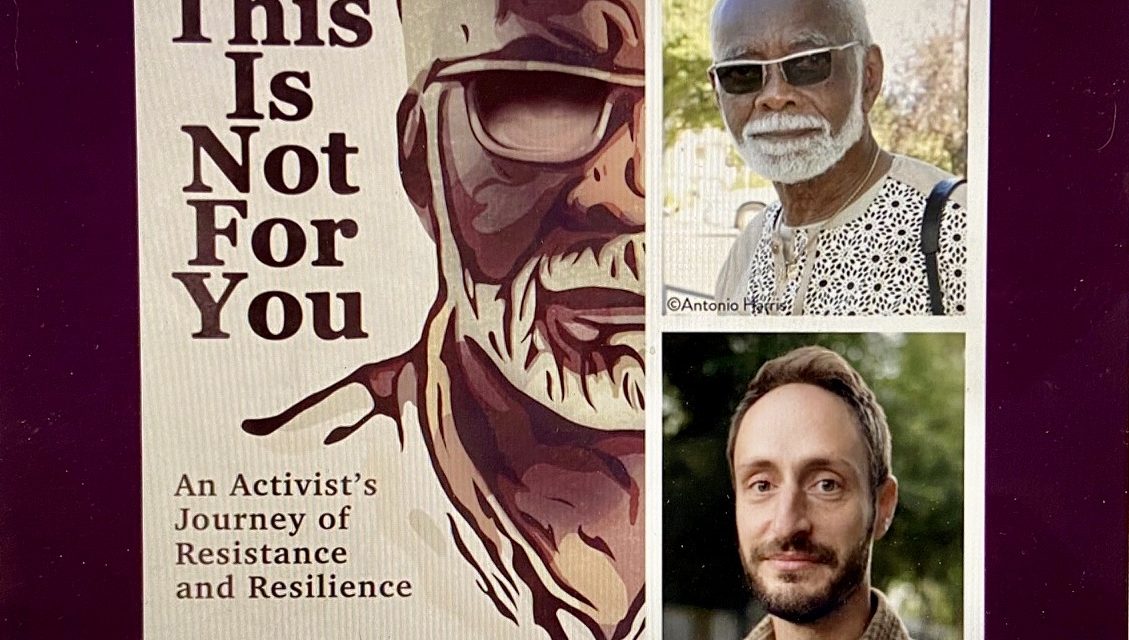

Title: This Is Not For You: An Activist’s Journey of Resistance and Resilience

Author: Richard Brown with Brian Benson

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis (2021)

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-484-3777); J Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

Richard Brown gets the final word, and it’s only fitting.

The 82-year-old native of New York City’s Harlem neighborhood — a high school dropout who discovered Portland in the late 1970s after 20 years in the Air Force — recounts with Brian Benson his childhood years, crossing the United States (as well as the Philippines, Saigon and Germany) in the military, his developed love and skill of photography and his almost accidental, then hard, relentless activism for community policing as well other community outreach programs.

Reviewer Daniel Buckwalter; photo by Randi Bjornstad

Along the way Brown has seen Portland’s streets at their worst, the old Black neighborhoods become largely gentrified. He has been a mentor to many, and all of it is captured in a concise memoir, This Is Not For You: An Activist’s Journey of Resistance and Resilience, which explores the weariness of being Black in the U.S.

The great author James Baldwin, a favorite of Brown’s, once noted in a radio interview that “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time — and in one’s work. And part of the rage is this: It isn’t only what is happening to you. But it’s what’s happening all around you and all of the time in the face of the most extraordinary and criminal indifference, indifference of most white people in this country, and their ignorance.”

Brown relates.

Early in his memoir, recalling a scene from 2016, Brown writes of a gathering in Salem of the Oregon Department of Public Safety Standards and Training, “aka the Academy,” that trains and certifies every law enforcement officer in the state.

Brown had once been a governor-appointed board member at the Academy, and when his term expired he was asked to be a civilian presence.

He hears yet another incomplete lecture of community policing from yet another white officer, and fatigued by it all, Brown writes that he walks up to the white officer and politely tells him of his 16 years’ worth of experience bringing police and Black people together through mayors and police chiefs to hammer out a civilized dialogue.

Then he thinks, long and hard.

“I’m tired of it all.

“I’m tired of having to work so hard to be heard. Tired of having to explain why I belong where I am. Tired of being ignored because I don’t have a badge, a bunch of abba dabbas after my name, a fancy title, a white face. I’m tired of saying the same things to people who aren’t listening, who don’t have enough urgency, who aren’t tired enough of watching Black boys die…

“And yet.

“I can already feel them, these old words, swimming up out of my chest.”

Brown did continue on, and while the names of Breonna Taylor or George Floyd or other Black civilians killed by police in the last year alone are not named, it is clear to Brown, from a scene on graduation day at the Academy in 2018, that the work is endless and always needs to be rehashed.

“I want to tell every cop in this room,” he laments to himself, “that so much could change if they’d just slow down, just wait a little longer to draw their guns, long enough to see they might not need to draw guns at all; that they need to stop talking about ‘fearing for their lives’ and ‘getting home safe,’ as if the people they shoot don’t want that, too; that there are so many smart, patient civilians who would listen to and work with them if they’d finally just step out of their blue cocoon.”

It’s a religious plea. Where it will fall in the years to come is anyone’s guess, but Brown now has a different worry: Who will take his place to work with law enforcement in community policing?

Brown’s multiple levels of community outreach and his photography work with The (Portland) Observer are perhaps singular in force. Perhaps it will take many hands in the minority communities to fill the many roles needed to lift up Black lives and all people of color. Perhaps we’ve seen the start since Floyd’s murder and the roar of Black Lives Matter.

“I’m not handing you any package,” Brown writes in the afterword. “What I’m doing, instead, is trying to trust you, like so many of my forebears trusted me, to make what you will of what and who came before. Trusting you to look at the paths and where they took me. Trusting you to take what you like, as you forge a path of your own.”

That brings up mentoring — which Brown has learned to acknowledge, and even to embrace the fruits of people who thank him for his generosity — and photography, a lifelong passion that he would fully embrace only after he left the military and settled in Portland.

Beyond his journalism work for The Observer, I’m struck by the portrait photos of Black people in This Is Not for You. I’m struck by the strength and dignity of the men, be they clergy, doctors, businessmen or fathers.

There are the women. “Black female role models are everywhere, in all walks of life,” Brown writes. “Well, you say, how come I never heard of them? There’s an African proverb I like, and I like to change one word: ‘Until the lionesses have their historians, tales of the hunted will always glorify the hunter.’”

Then there are the portraits of children, the sweet, kind, playful and thoughtful children. The final word belongs Richard Brown, and it’s only fitting.

“So once you’ve turned this final page, once you’ve shut this book and placed it back on the shelf, I hope that you will remember, if you remember nothing else, to ask yourself and your community and those who claim to be your leaders this question, as loudly and as often as you can:

“And how are the children?”