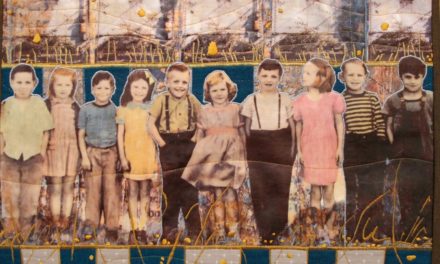

(Above: A Red Spoon, by Waldport, Ore., artist Jean Esteve)

By Randi Bjornstad

Although her college degree from Cornell University was in art, it has taken 92-year-old Jean Esteve all the decades since to launch her painting career.

Jean Esteve in a selfie — complete with artist’s beret — at age 92

“For me this is brand new,” the nonagenarian says. “I’d been intending to paint all my life, but I got nowhere with it.”

All those years ago, she started out studying art history, “but I’m really a doer, not a looker-oner. They had an art major, so I switched to that,” Esteve recalls. “But after I finished, I did zero art.”

Instead, “I had four kids,” she says. “I have read of people who have written books about doing artwork while having children, but I don’t know how they do it — I think I ended up playing Chutes and Ladders instead for all those years.”

That’s a bit too modest. Although she put painting aside, Esteve honed her skills as a poet and through the years created three chapbooks, defined as short collections of poems, usually 20-40 pages long, and stapled or stitched instead of bound. One of them, Off-Key, was a finalist for an Oregon Book Award in 2013. That same year, she also published a collection of poems titled The Winter Sun.

Born in 1929 on New York’s Long Island, Esteve had a childhood dominated by polio from the age of 2, but like the rest of her life story, she describes the situation with a humorous twist of irony.

“I was bedridden for a long time, and I did some drawing then — it was one of the things I could do to kill the time,” she says. “My polio was mainly in my legs; I had my last surgery when I was in fifth or sixth grade. After that, I was not a graceful dancer — I didn’t get cut in on very often at school dances.”

She lived in New York until she finished her degree at Cornell, and then she and George, her on-again-off-again husband, hitchhiked all the way across the country to San Francisco. During the years of their marriage she had three children, two boys and a girl. When the youngest of those three children was not yet a year old, her husband died by drowning. She later had one more son.

Decades later, Esteve decided she wanted a new life, and she wanted to paint. So she told her grown kids she was going to move to Oregon.

“I got a little truck, and I moved,” Esteve says. “But I still just couldn’t do the art, it just wasn’t working. I didn’t even like what I was doing then — but I do now.”

That’s when she started writing poetry in earnest, as well as doing whatever else she could to make a living.

“I did a lot of things — let me count the ways,” she says. “I did typing, picked up little jobs here and there, and I even wrote for ‘confessions’ magazines, ones like True Confessions. As soon as I would meet someone, I’d start asking all sorts of questions about their lives. So it was getting people to talk about themselves and how they met other people, and their relationships.”

Writing became a steady practice, but she still wasn’t ready to take up art again.

“I think I was more sure of myself with writing than art,” Esteve recalls. “And at Cornell, I had worked on a (campus) magazine. I was the art editor, but I also did writing.”

Although she’s done “serious” landscapes, Esteve says people often tend to gravitate toward her smaller pieces.

As she got back into painting, though, she realized there were similarities between the two, “creating composition by balancing words in poetry and colors in painting.”

What really made the difference in her painting, however, was a chance encounter with a different kind of paint that she found through a friend.

“My friend had some Dollar Store paints with funny names like Malibu Blue, stuff like that,” Esteve recalls, “and I started playing with them and really liked the thickness. So I started doing things, although I really wasn’t taking it seriously at all, and I found there were people who really liked what I was doing and wanted what I considered barely sketches. That really took me by surprise.”

She had done oils and acrylics earlier — landscape paintings of rocks and trees — but they didn’t get the same attention and appreciation as her more recent work, maybe because of a new looseness in her approach, Esteve surmises.

“I am serious about color, but maybe now I try a little bit more to just whip it out, not trying too hard, and maybe that’s what makes it easier for other people to understand and enjoy.”

She doesn’t paint every day, maybe because after all, she is over 90 years old — “I sleep, I paint, I sleep a lot,” she says wryly — but she spends several days each week at it. “Sometimes I sit down and I can’t think of anything, but I start anyway and just do what happens. Other times I get an idea and try to do it, and then I like the more premeditated look.”

Probably the greatest surprise of Esteve’s life was an unexpected, fairy-tale ending to a long-ago youthful relationship with a young man she knew in college but hadn’t seen since.

“After all my kids were raised, when I was in my 60s, I was in a period where I was feeling kind of low. I was looking through something Cornell had sent out and came across his name and address and sent him a letter. His name was Dan — Danny, actually — and we had been just friends, doing things like going to movies together.”

They exchanged a few letters, and she learned that he had never married, had a map-making career with the Federal government, was estranged from his family, and lived in Florida.

The artist gives this painting the wry name of “Thirst.”

“I just always liked him,” Esteve says. “He was really shy, and so was I.”

Then out of the blue one day, she got a telephone call from an attorney. Her old friend “had upped and died, and the lawyer told me he had left me everything,” she says.

At that point, “I realized I could afford to buy a house of my own, and I found it in Waldport,” she says. “I had a friend who was in real estate, and we looked all up and down the coast until we found the right place. If it hadn’t been for the inheritance, I don’t think it ever could have happened.”

Once settled in her new home — it’s been more than 20 years ago now — both her poetry and painting began to become an oeuvre. She joined a writer’s group called Tuesday that initially met in people’s homes but soon grew too large and had to start meeting in a church. Those sessions stopped with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and have not resumed yet.

The Tuesday group has published several volumes of poetry through the years. Volume 5, from Winter/Spring 2010-1011, for example, has five of Esteve’s poems in it, all of which previously had been published in various poetry magazines, including this, published first in the Iowa Review (presented here with slashes between the original lines):

I By The Riverside

I walked and walked/disturbing the river/that lurched alongside/the walker’s road.

“No one has walked/so fast so far/so far as I remember,”/the river roared.

Rivers do not/remember well./Last year I walked/this far this fast myself.

A mind that’s maimed/as much as mine, as you must know, has been,/needs months and months/of brisk walking.

I did not deign/to bicker, instead/I merely muttered,/”Hush river. Go to bed.”

And indeed,/it quieted.

Like her poetry, Esteve’s art also seemed to progress with her move to Waldport. “My kids were my first ‘clients,’ ” she jokes.

She worked for a time at the Touchstone Gallery in Yachats, and during that period the gallerist “went through my garage and took some of my larger, more ‘serious’ paintings,” Esteve says.

“But the only things that really sold well were my little sketchy things,” she recalls. “That’s probably what I should have been doing all along — trying to make a living doing the smaller things.”

Contact artist and poet Jean Esteve

Email: jeanesteve@yahoo.com

Facebook: facebook.com/jean.esteve

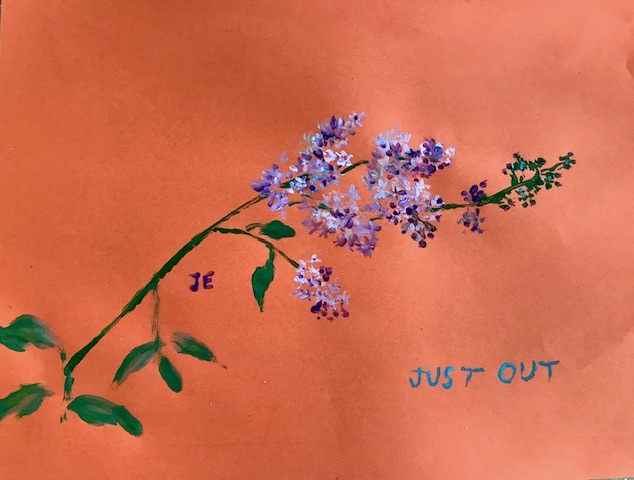

One of poet and artist Jean Esteve’s most recent paintings