Above: Ellen Tykeson’s masterpiece is a huge bronze installation of a family of circus acrobats titled “A Fine Balance,” installed in the RiverBend Commons outside the PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend in Springfield, Ore.

Below: How does this hospital environment affect the way we see this sculpture?

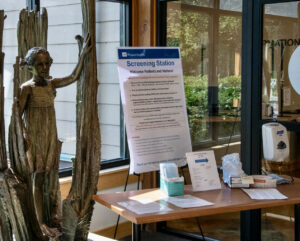

A staff member and patient pass by empty waiting area chairs and Ellen Tykeson’s bronze sculpture “Day of Days,” which sits in the main lobby of PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend.

Story and photos by Jordan Essoe

How does public sculpture alter a hospital environment? Does ornamenting the hospital grounds or lobby with sculpture make patients, staff, or facility donors feel more at ease? If so, more at ease with what? And how good does the sculpture have to be for this to work?

In return, how does a hospital environment alter public sculpture? Hospitals are the site of many successful bypass surgeries, hip replacements, and reversed narcotic overdoses. Large-scale sculptures aren’t placed in the treatment or operating rooms where services are performed, however. They aren’t found in inpatient rooms.

Sculptures are installed in public spaces often occupied by people in a state of anxious anticipation. The traffic of wheelchairs. The long hours waiting for news of loved ones. Is the meaning and interpretation of artwork broadened or narrowed in this setting?

Tykeson at Cottage Grove

Celebrated Eugene-based sculptor Ellen Tykeson has three separate bronze installations at two of the four Oregon hospitals owned by the Catholic-affiliated regional health care giant PeaceHealth, which commissioned the works.

The first bronze was completed in 2004 when Cottage Grove Community Medical Center reopened as a PeaceHealth facility.

Tykeson’s late parents, Don and Rilda “Willie” Tykeson, were longtime PeaceHealth supporters, retired PeaceHealth executive Tim Herrmann said. “Ellen, their daughter, is quite an accomplished artist in bronze. As part of the fundraising for Cottage Grove, they went to the donors and said they’d like to do a commemorative piece by Ellen.”

When Cottage Grove Community Medical Center reopened in 2004, PeaceHealth commissioned Tykeson to create the bronze sculpture “Journey,” which depicts a young girl parting the stalks of a slightly stylized wilderness.

Tykeson’s sculpture for Cottage Grove, titled “Journey,” features a young girl set between tall, fractured “fingers” of partially abstracted terrain. The Carrollian timber is populated in a few places by small birds, but the stalky fragments feel otherworldly, like basalt columns if they were made from plant fiber.

The girl is barefoot, wearing a dress, her hair in two small pigtails. Her posture is somewhat passive, though the folds of her dress indicate she is stepping forward or backward, and the position of her hands suggest that she may be parting sections of the landscape to emerge from it.

The tableau has an implicit association with fairy tales where a girl exits predatory woods, locating refuge in the civilized world. Script below the figure states: “This sculpture symbolizes the reemergence of hospital services in Cottage Grove.”

This text refers to the gap in access to local health care services that followed the closure of the original Cottage Grove hospital in the 1980s. The facility had first opened its doors to the public in the 1950s and its bankruptcy was part of a startling trend of rural hospital closures nationwide, after the U.S. Congress required fixed Medicare reimbursements through the Prospective Payment System in 1983.

Rural American hospitals are still shuttering at an alarming rate. In an aggressively corporatized health care environment, they are sometimes individually targeted by huge conglomerates that strong-arm suppliers and insurance companies, using their massive purchasing power to squeeze small community hospitals out of the market. In recent years, large health systems such as Sutter Health and ProMedica have been sued over such anti-competitive practices.

Most community hospitals can no longer survive without corporate purchase.

“There wasn’t enough volume in the small hospitals,” Herrmann said. “The only way to really move forward was to partner with bigger health systems. And that’s where you saw, primarily in the ’90s, a lot of consolidation.”

In Cottage Grove, “the local community came together,” he said. “They knew they needed a hospital and solidified a relationship with PeaceHealth.”

The back view of Tykeson’s “Journey” sculpture, viewable only from outside the Cottage Grove hospital facility, is animated by plants and their reflections in the window.

If you don’t read the text below “Journey,” as probably most casual viewers won’t, you are not likely to extrapolate any such message from the Tykeson bronze. You might consider the work to be a portrait, like her statue at the nearby Cottage Grove library that commemorates Oregon nature writer Opal Whiteley.

Whether you see the girl as a symbolic human being or a literal one, “Journey” enacts an interruption of space by a vulnerable, shoeless individual. It is probably the space in front of her that she is interrupting – the one occupied by the viewer – but it could alternatively be the space behind her.

Perhaps she is a hospital patient, potentially on her way to recovery. Yet medicine is not always curative (in the end, it’s never curative), and the girl’s journey could be going the other way, stepping backwards, with the fibrous trunk walls of the landscape closing in on her, making a coffin. These are the truths of hospitals.

“Journey” is installed in the vestibule between the outside door to the portico and the inside door to the hospital lobby. This is a space of constant movement, both by people and the two automatic doors they activate, which adds an interesting sense of chaos to the experience of the sculpture.

To stand and look at Tykeson’s work is to likely place yourself in the way of another person, someone trying to push through the space, as if the passageway and all its contents are only to be apprehended by a viewer in motion. The coming and going makes the tentative nature of the sculpture’s illustrated movement seem even more frozen and indistinct.

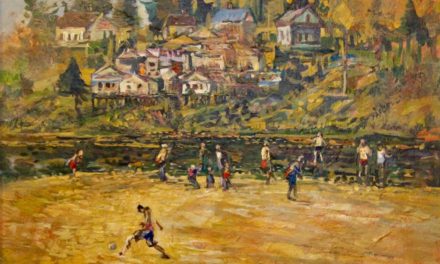

Artwork sometimes competes with the more mundane aspects of a medical facility’s functions, such in post-pandemic PeaceHealth’s Cottage Grove facility, where Tykeson’s “Journey” shares space with a sanitizing station.

Post-pandemic, “Journey” has also shared its limited floorspace with a desk holding masks, hand sanitizer, and signage directing visitors to use them. This complication of the spotless conceptual space Tykeson’s girl was designed to interrupt provides an interesting bit of additional disorder.

By default, the moving parts of hospitals treat all artwork within their milieu as unnecessary decoration and artwork treats any nearby hospital utility as visual interference. Here the two setups literally crowd each other, emphasizing the question of which is cluttering which.

Though the ad hoc Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) desk is something of an eyesore, the conflict of purpose it introduces into the vestibule invites a richer, more grounded art experience than Tykeson’s sculpture alone by giving us this concentrated microcosm of the overall clash, compromise, and potential mutual benefit of mixing art and hospitals.

Mitchell’s RiverBend

After the “Journey” commission, Tykeson continued to collaborate with PeaceHealth to produce what is up to now the most ambitious work of her career.

For the sprawling, dazzling PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend, she created two ambitious bronze installations, one indoors and one outside, both developed around the unexpected theme of circus performers.

RiverBend’s hospital building and site is a work of art itself, and one that controls the viewer’s relationship with the Tykeson bronzes.

The massive RiverBend complex during construction. It covers 161 acres of riverfront fields, groves and farmland and includes 1.8 million square feet of hospital and clinic facilities; photo by Turner Construction and courtesy of Ron Mitchell.

The medical center is located on the Springfield edge of the Eugene-Springfield metropolitan area, 20 miles north of Cottage Grove via Interstate 5. The landscape is bewitching, and so is the way the hospital’s landscape design indulges it with constructed gardens, walking trails, and park areas that serve pre-existing trees and echo the natural shape of the McKenzie River.

There is an alternate version of history in which the RiverBend campus might instead have been completed as a cheerless parking lot with a barren, routine hospital dropped in its center. PeaceHealth Oregon Regional CEO Allan Yordy fired the industry firm that proposed to do that.

Based on his faith in a modest concept sketch (that he immediately had framed for his office), he instead put in charge Ron Mitchell, a Seattle-based design architect known not for hospitals, but for crafting lavish hotels and resorts.

Mitchell had previously designed projects for the Ritz Carlton and the Four Seasons hotel chains and helped develop world-famous sites like the Venetian Las Vegas and the floating OQYANA World First in Dubai.

The architects Yordy had initially hired found Mitchell’s vision for RiverBend (the project name Mitchell coined) to be too far off their map.

“It’s not Disneyland here — it’s a very sophisticated medical center. And he doesn’t get it. He’s wrong,” the other architects said of him, according to Mitchell. “And I said, ‘Yeah, it’s true, I don’t know anything about hospitals.’ ”

Design architect Ron Mitchell felt strongly about preserving the natural landscape for the good of hospital patients.

Mitchell wanted a big meadow out front and conceived of the main road winding through the property like a body of water. He didn’t want any straight roads and he wanted to embed the hospital as much as possible within the existing landscape.

“Everyone wants to be against trees,” Mitchell said. “Nature is what inspires.” He thought every inpatient room should be a single, have a day bed to accommodate the overnight stays of family members, and have a unique view of the mountains, the river, or the trees.

A small but spectacular grove of Douglas fir on the southeastern side of RiverBend between the emergency department and the McKenzie River is supplemented with paths, tables, benches, lamp posts, and a gazebo. It is a significant feature of the grounds, but there was initially no guarantee that the trees would survive the site’s development phase.

“I fought very heavily for all those trees and won,” Mitchell said. “I was militant about it.”

There is one central, large Douglas fir in front of the main entrance, estimated to be 155-feet-tall at the time of the hospital’s construction. They nicknamed it “Ron’s Tree” after Mitchell threatened to quit if they cut it down.

Mitchell’s overriding design philosophy is that the physical site cannot conform to the project and the architect. The building project must conform to the site. The design must protect and articulate the site’s native anatomy.

Multiple people connected with the RiverBend project or PeaceHealth told me the motive behind generating and preserving beauty on the site was to create an atmosphere conducive to healing. They consistently mentioned studies that demonstrated better health outcomes and quicker recovery times for patients who had views of the natural world while recuperating from treatment.

“When patients are able to go out into nature, it’s very therapeutic,” PeaceHealth’s chief compliance officer, Jim Gryte, said. “The design impulse was about creating a healing environment by bringing as much nature into the building as possible.”

Hermann attributes this idea to The Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace, the Catholic order that owns PeaceHealth and has been providing medical care in the Pacific Northwest in some form since the 1890s. “Everything,” he said, “including the grounds, are part of that healing process.”

Mitchell said Yordy also just wanted the hospital to feel uplifting in the way a vacation resort was uplifting. It was the reason Yordy had searched for a hospitality architect, and he intended this uplifting experience not just for patients, but for anyone who entered the property.

“That’s why it feels like a lodge when you go into the main foyer there,” said Steve Reinmuth, who as owner of Reinmuth Bronze Studio has been casting Tykeson’s work for more than 25 years. “They wanted to give people the feeling they aren’t arriving at a hospital, they’re having a vacation.”

As you walk past a pool waterfall and Ron’s Tree (now over 170 feet tall) and approach the large porte-cochère over the hospital’s main entrance, with its stone pillars, wood beams, and glass lanterns, you may realize a couple of things. The first is that it does feel uplifting to be there. Its surfaces change your feelings. A sense of the cold and clinical (or even medical, depending on the level of suffering prompting your visit) is remote from your mind.

The second realization is that connecting with the building’s architecture offers a sense of buoyancy different than that experienced in the Douglas fir grove. The stand of trees feels luxurious in the way a great state park area is luxurious: the inherent magnificence of nature combined with institutional management for a little housebroken security.

The hospital entrance is uplifting, in part, because it sparkles with the dreamy endowments and broad-ranging security of significant private wealth. That is not all this architecture has to offer, but the lure of homey opulence is plainly foregrounded. It invites you into a fictional space adjacent to its physical reality that is operated by fantasies of ease, peace, and comfort.

“You’ll be received in a great big lobby, where you’re being greeted warmly,” Mitchell said of his concept for the entrance. “The whole thing is to create a welcoming environment that exudes warmth. You’re not just checking in. You’re not just being administered.”

There are some notable aesthetic similarities between RiverBend and PeaceHealth’s Cottage Grove hospital. Both campuses embrace a variation on Pacific Lodge architecture, with abundant use of exposed wood and stone, high ceilings, ample natural light, and a soothing, organic color palette.

But the 40,000-square foot Cottage Grove is comparably small potatoes in scale, style, ambition, natural assets, and power. In terms of the questions posed in my opening paragraphs, what this means is that while Cottage Grove’s influence over its sculpture is apparent, it’s sway is absolutely dwarfed by the magnetically persuasive leverage exercised by RiverBend.

Day of Days

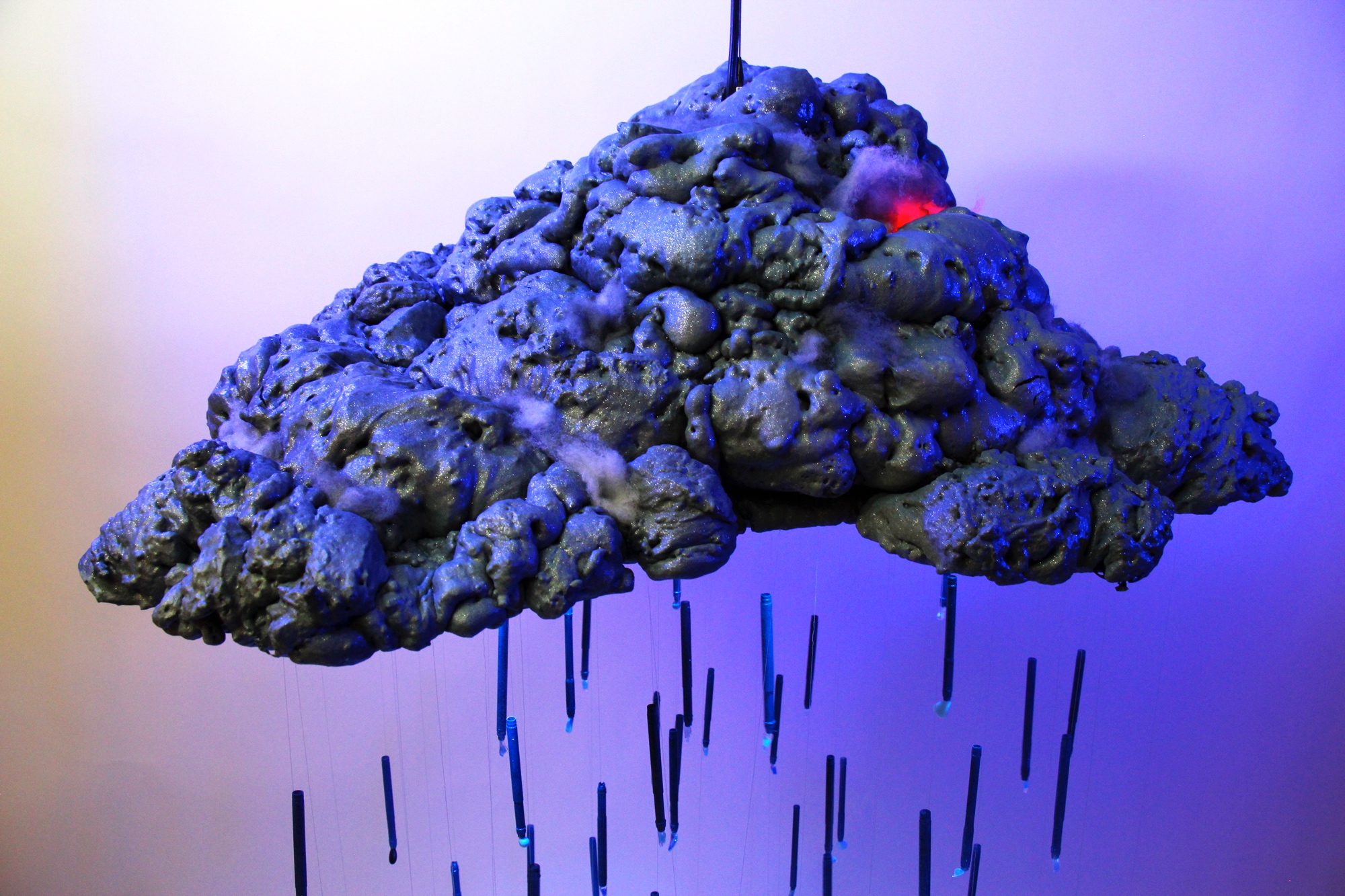

Tykeson’s “Day of Days” in the lobby at RiverBend offers abundant airspace between the circus performer and the skylights she stands beneath.

In the center of the RiverBend lobby, between the front desk and the large multistory stone fireplace, is Tykeson’s bronze “Day of Days.” This smaller-than-life-size sculpture depicts a young woman in a circus costume standing on the bare back of a horse. She holds a perched parrot on the right and a performance hoop on the left.

One of the first things a viewer will notice is the first-rate quality of the sculpture’s textures and classically articulated form. Tykeson is exceptionally good at modeling and doesn’t cheapen the surface of her finished bronze by polishing it to a shine.

The woman’s bare feet are spread, one further back on the horse’s loin, both firmly planted and not poised for vaulting. All four horse hooves are up – making both animal and woman fully airborne – indirectly recalling Eadweard Muybridge’s 1878 stop motion photography that proved a galloping horse regularly lifts all legs from the ground.

Not being earthbound is a theme conceptually important to all of Tykeson’s RiverBend works. It ties into the title, “Day of Days,” if the title is interpreted as meaning a monumental event, or, to reference another milepost in the history of art, a decisive moment.

The equestrian performer is presumably ready to begin any number of acrobatic feats, but she doesn’t seem correctly braced for the horse’s propulsive trajectory. She looks like she might fall upon the landing. Yet her expression is placid, her mind faraway.

This emotive neutrality is a significant part of the sculpture’s success, for a couple of reasons. Artwork too easily comes off as cloyingly insincere in a hospital setting. The drama of Tykeson’s circus performer leans into the absurd rather than the spectacular or passionate, and her detached expression makes room for a viewer’s curiosity. The performer’s internal world becomes defined by whatever external information the viewer desires to combine with it.

There are other sculptures elsewhere in the building by different artists that do not avoid sentimentality, but they are not on central display. Reinmuth said “Day of Days” was originally going to be sited in a more remote upper floor, but the PeaceHealth team liked it so much they moved it to its current location, where it demarcates the start of the main lobby’s waiting area.

A waiting area is a very specific micro-environment: an encampment for strangers with a shared sense of helplessness and an inward, distorted account of time whose central mysteries — “what is going to happen?” and “how much longer do I have to wait?”— reverberate with the companion question, “how long have I been here?”

The waiting area chairs hold visitors who stare down at devices or other reading material without reading it. Anticipating a call to go to the recovery room. Not wanting to leave the waiting area to go to the bathroom or get a snack for fear they will miss a conversation with the doctor. A conversation that will inevitably seem incomplete because in hospitals uncertainty is always in greater supply than any imparted information.

A waiting area is described by its island of chairs, but it is defined by an urgency for departure. It is defined by entrances and exits. Different kinds of exits emphasize different things. Some confirm the predicament of the waiting area, and some offer a vision of escaping it.

How do sculpture and architecture interface with a hospital waiting area? Waiting area anxiety may be partly soothed by an architectural space containing symmetry, elaborate angles, and a high ceiling. Symmetry is calming and angles can direct energy upward.

A high ceiling is a spatial and visual exit that gives restlessness somewhere to go, especially if there is a skylight. Mitchell’s towering lobby atrium has several sections of skylight, magnificently placed at the roof’s peak, so each glass section gently divides at its center and bends toward itself.

Other exits in the space are more literal, the most romantic being an imperial staircase on the other side of the fireplace. Less literal exits are introduced by “Day of Days,” whose primary interest, whatever its other concerns may be, is the body.

The routines of a hospital constantly remind us that the body is something we enter and exit from, whether through sleep, painkillers, anesthesia, or death. As patients, we’re constantly reminded the body is “ours,” but it isn’t “us,” and that our consciousness is but one thing that passes through it.

The body is riddled with entrances and exits which the practice of medicine demands access to — the mouth, ears, nostrils, urethra, vagina, anus — and the hospital constructs its own supplementary holes and passageways with its syringes, catheters, ports, and incisions. This is the body as a series of gates, not unlike a piece of architecture.

Figurative sculpture has a unique ability to comment on this intimate yet dehumanizing materiality. To this advantage, Tykeson made the notable choice of detailing the anus and vulva of the horse. This is anatomy puerilely avoided in most public sculpture, even when depicting animals, but it’s particularly relevant here.

Details in Tykeson’s “Day of Days” include an intricately detailed woman’s figure topped by a beehive and an apple, drawing together concepts that capture the relationship — and fragility — of the human body to its own lifespan.

The performer has exposed nostrils, one partially exposed ear, a parted mouth, and — as part of a sculptural convention that gives visual depth to the iris and pupil through cast shadows — gaping cavities for her eyes.

If a viewer refuses the intended illusion created by the ocular shadows and sees the sculpted shapes for what they are, alarming hollows come into view. Craters that swallow most of the eyeballs, making room for unspecified entrances and exits into the woman’s interior.

Balanced on her head is a beehive. It has its own central entrance-exit hole that mimics the woman’s eye, mouth, or other body cavity. But it also returns us to thoughts of architecture. The hive is a capsule of tiny architecture with a high ceiling. And from a dreamy point of view, it could be a dollhouse version of the lobby, illustrating something of the exquisite fragility of any group of lives gathered together in an enclosed space.

There is an element of danger for the precariously balanced hive, but also an element of danger from the hive, in the likely event that the bees will be jostled as the performer attempts to have them for a hat while simultaneously standing on a leaping horse.

Further complicating stability is an apple set on top of the beehive. The fruit’s position summons images of the legendary arrow shot by William Tell, under the threat of death, at an apple resting on his son’s head. And, by association, the accidental shooting death of Joan Vollmer by her husband William Burroughs as the couple performed their “William Tell act” at a party.

The risk of death is the energy that haunts both the waiting room and the circus performer. Circus acts are often described as death-defying, and to defy death is also the goal of medicine. There is an escalating sense that much of the “Day of Days” imagery participates in this dialogue about the decisive moment between living and dying — a leap between the two, perhaps toward living, perhaps toward dying, but frozen in transitional uncertainty, like many waiting room visitors imagine their loved ones to be.

Through general anesthesia, hospital patients are kept in their own isolated state of waiting. Its limbo keeps the bodies of patients still and spares them consciously experiencing the horrors of being cut. They exit suffering by exiting the body.

Before anesthesia was perfected, surgery was purportedly often conducted on the highest hospital level so the screams could not be heard on the ground floor.

The first surgery with successfully administered anesthesia was done in a high floor operating theater in 1846, under a beautiful skylight dome. The patient was an artist and the site at Massachusetts General is now known as the Ether Dome.

If you perceive the equestrian performer of “Day of Days,” with her tilted, doped expression, as well-suited for an allegory about the limbo of anesthesia, then the enormous air space surrounding the sculpture stands in for a kind of Ether Dome, the waiting area chairs standing in for the observation tiers.

Or, if you take the performer elements more literally, Mitchell’s broad lobby architecture can just as easily be a spatial surrogate for the circus big top. A tent that showcases suspense even more than it does the defiance of death. A tent that, like a hospital, elevates the human body while towering over it.

A Fine Balance

Tykeson’s artistic tour de force on these themes, however, is not found in the building.

To get to it you must go back outside, head away from the main hospital entrance and McKenzie River, pass Ron’s Tree and the garden pond and lawn that precede it, and then cross the street.

On the other side of RiverBend Drive is a spread of grass with intermittent trees called the Riverbend Commons. This park area may eventually be utilized as part of a future hospital expansion, but today it’s just the quiet site for a walking path and Tykeson’s breathtaking installation, “A Fine Balance.”

The dog is the only figure that touches the ground in Ellen Tykeson’s richly detailed bronze installation titled “A Fine Balance.”

This is a life-size, multifigure bronze sculpture depicting an entire family of circus acrobats. It’s reminiscent in some ways of Picasso’s 1905 painting, Family of Saltimbanques.

Tykeson uses almost the exact same number, sex, and ages for her troupe as Picasso did, but trades one of the painting’s young boys for a dog, and adds a cat, which hangs in a sack at the feet of the eldest man.

In a dramatic departure from Picasso, Tykeson’s acrobats are all stilt walkers. Only the dog is earthbound. Carrying forward the theme from “Day of Days,” no one else touches the ground. The dog is up on her back legs, tugging on a performance hoop ringed around the foot of the youngest boy, seemingly yearning to join the rest of the family up in the air.

Because it is placed outdoors by itself, away from general foot traffic, encountering the bronze by chance feels like an extraordinary discovery. The installation is sizeable, with most of the stilts elevating figures six feet or more above the ground. Framed from below by a circular pad of pavestone, the work creates its own center of gravity, sense of territory, and sense of privacy.

Detail of the adult male stilt walker from Tykeson’s “A Fine Balance” on the grounds of PeaceHealth’s RiverBend Medical Center.

“It surprises me how few people know it’s there. When most people come to the hospital, they’re looking towards the building and away from the sculpture,” Reinmuth said.

He described how “A Fine Balance” was originally going to be installed on the main road, but the site was moved due to worry about potential for damage to the one-of-a-kind $250,000 sculpture caused by possible car accidents.

The slightly removed location limits not just the number of overall viewers, but also the number of viewers that might need a cane, walker, wheelchair, or ongoing IV or oxygen therapy — people in no small supply in and around a medical facility.

This separation becomes part of the gestalt of “A Fine Balance,” which overlooks the hospital without being inside its nucleus. It functions in reference to but also stands apart from the halls of treatment.

This leads one to consider the nature of the performers’ stilts.

As rigging that enhances detachment, it becomes reasonable to think that the world of physical limitations and suffering are the very things the stilt walkers are seeking to rise above. Dysfunctional bodies that cannot, without help, freely perform simple tasks like walking, eating, breathing, or using the bathroom, are to be escaped from. Pain is to be fled from, like in the act of running away to the circus.

Detail of the boy stilt walker from Tykeson’s “A Fine Balance” on the grounds of PeaceHealth’s RiverBend Medical Center.

Pain and suffering create a sense of failure. Of having failed at being healthy, being a survivor, a champion, a warrior. The boy stilt walker looks down at the ground, and the begging dog, with remove. Is the boy suffering? Is the dog? Society used to believe that animals like dogs didn’t feel pain. Used to believe that babies didn’t feel pain. Used to believe that those of us with darker skin didn’t feel pain.

If the suffering is someone else’s, you may be able to escape it by making yourself scarce. If the suffering is yours, there are fewer options. To be healed, if that is possible. To transcend it through meditation or other mental or spiritual practices. To dilute the pain with drugs. Or, death.

A young girl with fairy wings floats among the other acrobat sculptures, perhaps a symbol of both life and death inevitably encountered by those who devote their lives to providing medical care.

The youngest member of Tykeson’s troupe is a little girl with fairy wings who does not stand on her stilts, but floats alongside them. She appears to be holding the stilts upright rather than the other way around. A viewer could perhaps see her as mid-air in a performance of banquine, but there is no team of performers that might have launched her into motion, and there is no one waiting to catch her.

One implication may be that the child is dead, and that her flight represents a permanent uncoupling from worldly suffering. Or perhaps she is merely in some temporary state of escape, initiated by narcotics or hypnosis. Her face communicates bliss, but her remaining, brushing contact with the stilts suggests a hesitation to withdraw wholly.

Balance is often something that needs to be believed in and not focused on too tightly or it falls apart. Just how steady is the balance Tykeson presents us with in “A Fine Balance?” Is it “fine” as in first-rate or “fine” as in slight? Notably, the acrobat who seems the most at ease with her balancing act is the one who stands the furthest from the ground and performs a complicated secondary stunt — freeing birds from a cage.

Whether the flight of the birds is a symbol of hope or death, it is another undeniable gesture of escape, accentuated by a set of rings that hangs from the cage and echoes the vacancy that will emerge once the last bird flies off.

The stream of departing birds physically connect, wing to tail, head to tail, one after the other, arcing up above the stilt walker’s head as she watches them ascend. Both aesthetically and technically, it’s remarkable.

Detail of the adult female stilt walker from Tykeson’s “A Fine Balance” includes a delicately composed, ethereal flight of birds.

“What Ellen did with those was very challenging,” Reinmuth said. “She really wanted to create kind of a weightlessness. Something that was precarious.”

To achieve the effect, Tykeson and Reinmuth cast a whole bunch of the birds and then, in a slightly improvisational process, assembled the final arrangement on site at RiverBend through trial and error. Tykeson would hold one bird where she wanted it, and Reinmuth would weld it in place.

“A Fine Balance” comprises about 100 separate sections in total. Reinmuth said he’s worked on sculptures that required more parts and contained more elaborate detail, but no bronze has been more technically challenging for his shop. In addition to executing eye-catching touches like the flying birds, he had to create a vast network of stainless-steel armature inside every bronze figure, work with the site engineers to plan support rods for every stilt to reach four feet underground, and help design the few unfixed elements, like the performance hoops, so that they are able to sway in the wind.

The ambition of the sculpture corresponds to what Tykeson’s father, who was one of the leaders of the capital campaign for the construction of RiverBend, tried to inspire within everyone who worked on the project.

“(Don and Rilda Tykeson) were donors and were very instrumental in terms of helping us think big,” Hermann said. “Mr. Tykeson quoted architect Daniel Burnham from the book The Devil and the White City at one of the meetings: ‘Make no little plans – they have no magic to stir men’s blood.’ And it became the mantra for the campaign for RiverBend.”

This philosophy also corresponded with Mitchell’s ideas.

“It’s probably the most meaningful project I’ve ever done,” Mitchell said of the hospital.

He told me that in contrast to his hotel projects, where the goal was mostly to create a seductive place for people to watch the sunset and have a drink, RiverBend allowed him the opportunity to do things like consider the needs of children undergoing chemotherapy and design rooms especially for them.

How does Mitchell’s desire to create uplifting, healing spaces meet the more emotionally complicated terrain of Tykeson’s stilt walkers? A reading of the stilt walkers as harbingers of hope is possible.

We know that beyond the quality of the health care we receive, what matters most for our overall well-being is our daily lifestyle and environment. The stilt walkers are active, social, artistic, athletic, and skilled. They have passion. They get out the house, off their screens, play, and exercise. They project health in this way, and offer hope in this way.

But the most uplifting thing about Tykeson’s sculpture is that it’s good art. The ease it creates in the viewer is the sense of being told something genuine. Themes about escape and suffering make the work relevant and exciting. It can’t be overstated how worth celebrating and rare this is in public sculpture. So much garden variety public art is only there to monumentalize the wealth of the business that paid for it.

PeaceHealth deserves great credit, and Tykeson surely has the hospital environs to thank for some of the rich meaning that comes across. Some of the resonance of “A Fine Balance” would be lost if it were sited anywhere else but on hospital grounds. The pastoral RiverBend campus that encourages introspective, mindful walks, is particularly well-matched. Reciprocally, the hospital’s atmosphere gains more complexity, authenticity, and integrity from the presence of her work.

The Ether Dome and the Big Top

But what is the bigger context here? The state of the American health care system is grim.

We spend a lot more on health care than any other country — making it the single most expensive part of many citizens’ lives and responsible for most personal bankruptcies — and yet positive health outcomes keep falling below those in other developed nations.

In 2021, The Commonwealth Fund ranked the United States last when measured against 11 other wealthy countries on access to care, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. Americans continue to develop heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity at an explosive rate. Life expectancy is declining. Suicide is up. Infant mortality is rising. And so are the profits of our drug companies, medical device manufacturers, and the insurance industry.

The pharmaceutical industry operates largely unchecked. Drug prices are unregulated and out of control. Drug companies are allowed to directly market to American consumers, seeking to make even the healthiest among us into addicts, which almost no other country in the world permits. They largely control the information doctors receive about the drugs they are selling. Most peer reviewers and editors of respected medical journals do not have access to underlying drug trial data, only drug company summaries, and many doctors don’t even realize it.

As the corporatization of health care continues to thicken around us — as advertising agencies and pharmacy chains run clinical drug trials, as giant retailers get into primary health care, and as more insurance corporations and pharmaceutical companies look into managing their own health systems — what hope do we have for transparency or an industry that optimizes care over profits?

Because RiverBend feels good, it makes you want to feel good about health care, and makes you want to believe that a better future is available.

A future where society embraces upstream care and our government insists on transparency and regulation and universalized health coverage. A future where large health systems like PeaceHealth join together and use their combined purchasing power to stand up to pharmaceutical companies, medical device manufacturers and the insurance industry, and aspire for greater patient care improvements beyond making handsome, local healing environments.

Above our heads is the ongoing merger of the Ether Dome and the big top, combined into one business, where the most significant participants are not the waiting audience members or even the performers, but the people selling the tickets.

If this system progresses, as it is likely to do, the reflection cast by the anesthetic escapism of Tykeson’s children in the woods, equestrian vaulters, and stilt walkers will only become more germane, urgent, and haunting.

About the author

Jordan Essoe is an award-winning artist and writer who has exhibited and published internationally. Primarily a painter, his practice broadened to include film, performance art, playwriting, and journalism. His work has been covered by NPR, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Oakland Tribune, Artnet, Artillery, Art Practical, Art Week, and Rhizome.

A view of the western side of PeaceHealth’s RiverBend medical facility where the garden pool designed by Ron Mitchell evokes the presence of the McKenzie River on the opposite side of the complex. Sculptures by Ellen Tykeson are installed both inside the main hospital lobby and across the street in the RiverBend Commons.