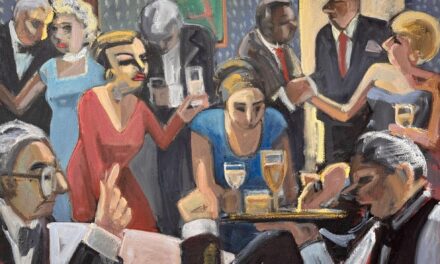

Photo: Randi Bjornstad

By Randi Bjornstad

One of the recurring themes of Kathleen Caprario’s art is justice, whether social or environmental, and both topics come to the fore in the two projects she now has on view in the Lane Community College Art Gallery.

The most startling is “White Noise/The Peacekeeper,” which addresses the dual issues of white privilege and the ever-growing list of black men — and some women — who have been shot to death by law enforcement officers in this country.

The installation consists of a large timeline on white paper tacked to the wall, divided into increments representing each day since the beginning of 2012. Marked on the timeline are the dates and names of people who have lost their lives in that time during fatal encounters with police officers.

A nearby pedestal has a video screen sitting on top, showing a perpetually changing pattern of static. There’s a pair of earphones connected to it that offer the same perpetual static in the form of white noise, except for an occasional “blip” that represents the day when someone lost his or her life to police violence.

It’s a different way of considering the frequency with which these deaths occur, either just by waiting for the next blip or anticipating it by following along on the timeline.

At one point near the beginning of the 4-minute video, there’s a bit of narrative and a photograph of a stunning but chilling sculpture made of plaster casts of handguns that was created by artist Marissa Solini, one of Caprario’s former students at Oregon State University.

“I instigated this project after the killing of Walter Scott in 2015,” Caprario said. “When that happened, I went on Facebook and posted my outrage in a mini-rant in which I said, am I the only person who is outraged by this — is anyone else — and I got two responses. The silence was deafening, and it made me determined to make some response to this terrible situation.”

She hopes her effort will make others think about the tragedies themselves but also about being part of a segment of society that rarely has to think about such things.

“I realized how much my own views are framed from the ‘white’ perspective, which is the only one I have,” Caprario said. “The idea of implicit racism is something most of us don’t even consider, but it exists in the fact that we don’t have to get up every day and worry about certain things that could happen to us simply because of our color.”

A decade or so ago, she took an anthropology class at Lane Community College that helped her become aware of white privilege, Caprario recalled.

“The teacher was wonderful, and the class was all white people,” she said. “One of the first exercises we did was to spend one minute writing down words that identified us. When we talked about them afterward, the teacher pointed out that not one of us had written down the word ‘white’ to describe ourselves. We were the dominant group — that was part of our white privilege.”

The other part of her show, titled “bioDIVERSITY,” has a more traditional feel but also addresses people’s relationship to their environment, this time natural rather than social.

It consists of a half-dozen mixed-media paintings that include papercuts and stencils — overlain with tiny tracks that mimic the flight patterns of birds and the scurrying of insects — that raise the question, “How am I shaped by my environment?”

This project came about through an artist residency at the PLAYA Foundation in Summer Lake, which Caprario funded through a mid-career artist residency award she received from the Ford Family Foundation.

“I’ve always been interested in patterns, and just as I looked at the patterns of police shootings from a social perspective, I looked in ‘bioDIVERSITY’ at patterns in nature from the environmental perspective,” she said. “

When humans examine the landscape, they assign different levels of beauty to it, which also means assigning it a value as a commodity, Caprario said, “and once we ‘commodify’ something, we inevitably raise the issue of whether we save it or destroy it.”

Referring back to the “White Noise” project, “Unfortunately that too often applies to people as well as landscapes,” she said.

In “bioDIVERSITY,” Caprario drew on the nature she observed to create a color palette, then created stencils of shapes, including avocet birds and cattails, covering the natural shapes with acrylic wash, concentrated watercolor “and a bit of white for highlight.”

The result is a rich series of patterns that sometimes appear by themselves, other times intertwine with other parts of the paintings and occasionally disappear into deep, all-encompassing wells of color and light.

The largest painting in the group, called “Refuge,” incorporates a series of intricately cut-out patterns that represent the lake bed of Summer Lake, which dries up every year, leaving the earth exposed, the ground cracked into myriad bits of irregular shapes.

“I assumed at first this was a natural event,” Caprario said. “Then I learned that the level of the lake is affected by a reservoir upstream and by the water rights of farmers and ranchers, and all that affects how much water is left for the bird refuge and Summer Lake downstream.

“I had made one assumption, and then I came to understand that human intervention, as much as anything else, had created this pattern. In this series of paintings, I was able to explore and portray the relationship between perception and reality.”

Even so, Caprario said she tried to leave the “bioDIVERSITY” paintings vague enough to encourage viewers to develop their own reactions to it.

“I may have a point of view, but I always want to let people come up with their own,” she said. “And I’ve always found that the viewer often surprises me.”

Lane Community College Art Gallery

Kathleen Caprario: “White Noise/The Peacekeeper” and “bioDIVERSITY”

When: Through Nov. 10

Where: Building 11, LCC main campus, 4000 E. 30th Ave., Eugene

Hours: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Thursday, 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Friday

Information: 541-463-5409