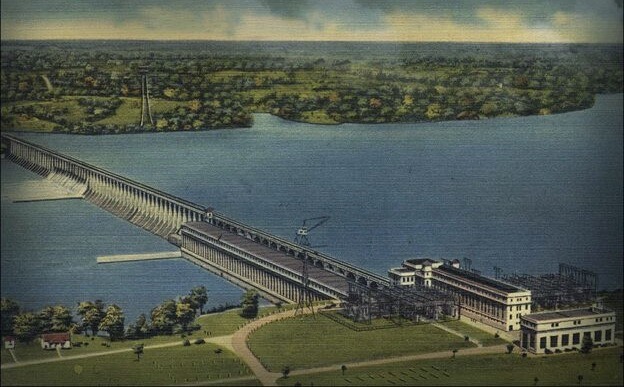

(Above: A detail from the cover of Thomas Hager’s new book, Electric City: The Lost History of Ford and Edison’s American Utopia)

By Randi Bjornstad

If author Thomas Hager had said “no thanks” instead of “why not” when his ride to the airport asked if he’d like to see something interesting, his new book, Electric City: The Lost History of Ford and Edison’s American Utopia, probably never would have happened.

A decade or so ago, Hager appeared at a convention in Muscle Shoals, Ala., to give a talk to the International Fertilizer Development Center, a nonprofit whose purpose, according to its website, is to “alleviate global hunger by introducing improved agricultural practices and fertilizer technologies to farmers and by linking farmers to markets.”

He got the gig because of a previous book that he wrote — The Alchemy of Air: A Jewish Genius, a Doomed Tycoon, and the Scientific Discovery that Fed the World but Fueled the Rise of Hitler — that delved into the creation by two German chemists of synthetic nitrogen, which not only could be turned into fertilizer to help to stave off impending global famine but also used to manufacture gunpowder to enable international war.

But don’t be fooled by the length of Hager’s titles. His writing style is a lively and entertaining combination of historical personalities, events, and their intersection with scientific facts and principles.

Eugene author Thomas Hager on the Oregon Coast

The earlier book “was a surprise hit,” he says. “It opened a lot of doors, including the invitation to speak to that fertilizer group in Alabama.”

Hager acknowledges that his approach “is a little unusual for a science writer.”

“It’s somewhat of a challenge to make this kind of writing come alive, to make it all work together so that it includes the human element along with the science and how all of it fits together in history,” he says.

So with that in mind, it’s not surprising that when the person driving Hager to the airport after his Alabama speech about fertilizer development wanted to show him the remains of a pair of old nitrate fertilizer plants on the outskirts of Muscle Shoals, he was intrigued enough to take the detour.

But it wasn’t really the carcasses of the factories that caught Hager’s imagination. As they drove on, he began to see the overgrown remains of streets, sidewalks, even century-old fire hydrants. His guide told him they were what was left of a city — intended to be called Ford City — that had been planned and laid out in the 1920s but never completed, and that the entire failed experiment had been the pipe dream of two American industrial titans, Henry Ford and Thomas Edison.

Intrigued, Hager returned home, did some library and online sleuthing, and soon headed back to Alabama to talk to historians and look at local records and newspapers. From there he traveled to the Ford Archives in Dearborn, Mich., and then on to National Archives in Washington, D.C., where the amazing story of this little-remembered, decades-long political and economic intrigue began to reveal itself.

“It was those three things — the remains of an unbuilt city, the abandoned factories, and the name of Henry Ford — that brought it all together, and the more I found out, the more it grew,” Hager says. “Today, few people seem to know it even happened. Like Ford City itself, it became just decay and weeds.”

It doesn’t always happen, of course, that a subject so mysterious and seemingly compelling works itself into something real and finally into book form, he says. “I’ve probably had at least 25 ideas that I have looked into that just didn’t pan out — they were interesting ideas, but maybe the characters weren’t compelling or important enough.”

This story, however, had great characters — the rich and famous Henry Ford and Thomas Edison, dubbed “Twin Wizards” by the popular press of the time — and their chief antagonist, George Norris, a U.S. Senator from Nebraska, who battled their plans for years and ultimately defeated them, without a doubt aided by the onset of the Great Depression and the subsequent election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal to the presidency.

In a nutshell, the fight was over who in the end — the government on behalf of ordinary citizens or private entrepreneurs in search of profit — should control the vast hydroelectric, and therefore financially profitable, promise of the Tennessee River. But if this sounds dry, Hager’s spinning of the tale through decades of twists and turns is anything but.

The very first paragraph in Chapter 1 is a perfect example of his talent for turning facts into story: On a map, the Tennessee River looks like a big crooked grin that starts in the upper right, in the Allegheny Mountains of eastern Tennessee, then flows west and south through the top of Alabama before it curves back north and west completing the smile about seven hundred miles from where it started …

He sums up the “social history” of the area — the thousands of years living there by the Native people, followed by trappers and adventurers such as Daniel Boone, and later attempts — often unsuccessful — by people determined to take control of the area for agriculture and development of cities. He charts the changes that came about during the ascendancy of Andrew Jackson from settler to lawyer to land speculator to soldier to plantation owner to judge to senator, all the while engaged in clearing the Tennessee Valley of Native people, which he concluded after becoming U.S. president when he signed the Indian Removal Act, forcing tens of thousands of Native people to move west of the Mississippi River.

All that cleared the way for cotton crops, huge plantations, and slavery, followed after the Civil War by industrialization that included Thomas Edison’s scientific genius in harnessing electricity and Henry Ford’s mechanical genius that led him to invent the assembly line and produce millions of cookie-cutter Model Ts, making him the richest man in America.

It was practically inevitable, Hager says, that the two met each other and became part of a team. “Ford worshipped Edison, and Edison liked adulation,” he says. “And what they both were trying to do, Edison with the expansion of electricity and Ford with making cars affordable to ordinary people, made them natural partners.”

That included their joint realization that the dirty, smoky, costly power that resulted from burning coal mined in areas such as Alabama could be replaced by electricity generated from the fast-running rivers of the Tennessee Valley, and they — especially Ford — expanded that vision to creation of an urban utopia called Ford City.

Electric City, by Thomas Hager, tells the story of industrial geniuses Henry Ford and Thomas Edison — dubbed “Twin Wizards” by the 1920s press — and their ambitious plan to create an American utopia in the state of Alabama.

In Electric City, Hager traces the machinations that dominated national politics for a decade as the “Twin Wizards” and their representatives lobbied the U.S. Congress, and even presidents, in an effort to gain private control — subsidized by a massive 100-year federal loan — to build not only a system of dams to send electric power to homes and factories far and wide but also to serve a 75-mile-long utopian city, where ordinary people could live in small towns and drive their cars — Fords, of course — to the factories and stores where they lived and shopped.

All those plans were slowed to a crawl by the perennial opposition of Sen. George Norris and his like-minded colleagues who firmly believed that the public benefit of electricity depended on public ownership and regulation.

They came to a screeching halt with the stock market crash of 1929, which paved the way for FDR’s path to the presidency and the New Deal’s raft of federal-centric recovery programs that included government regulation of water power and navigation under the new Tennessee Valley Authority.

All this is a lot to condense into one nearly 300-page book, but Hager manages to do it in a “and-then-what-happened” manner. He even appends a chapter-by-chapter rundown of where he got his information, along with some additional anecdotes that didn’t make it into the text proper.

In a way, Electric City is a departure from some previous Hager titles, which focused more closely on science or medicine rather than, as this one does, on the social and political machinery of the early 20th century. But his ability to recount technical details in story form reflects both Hager’s educational background and literary bent.

“I was raised in Portland (Oregon), and I went to Portland State University in biology, where I got interested in microbiology because of a really good teacher I had,” he says. “I got a master’s in medical microbiology, but then I realized I wasn’t cut out for the repetition and detail of laboratory work.”

He dropped out of the idea of pursuing microbiology as a career, “but I didn’t want to waste all that education,” Hager says. “I also loved writing, so I went to the University of Oregon (in Eugene) and got a master’s degree in journalism.”

After that, he worked at editing, “and then I realized I really liked the idea of telling real stories in detail,” he says. “It all took awhile.”

He describes himself now as “science writer, speaker, editor,” and he already has embarked on his next project, which he says has to do with “phosphorus.”

Purchase link for Electric City:

Some additional books by Thomas Hager

Electric City: The Lost History of Ford and Edison’s American Utopia; Abrams Press New York (2021)

Ten Drugs: How Plants, Powders and Pills Have Shaped the History of Medicine; Abrams Press, New York (2019)

Understanding Statins: Everything You Need to Know About the World’s Bestselling Drugs — And What to Ask Your Doctor Before Taking Them; Monroe Press (2016) — one in a series called Naked Facts: Simple Solid Science

The Alchemy of Air: A Jewish Genius, A Doomed Tycoon, and the Scientific Discovery that Fed the World but Fueled the Rise of Hitler; Harmony/Crown (2008)