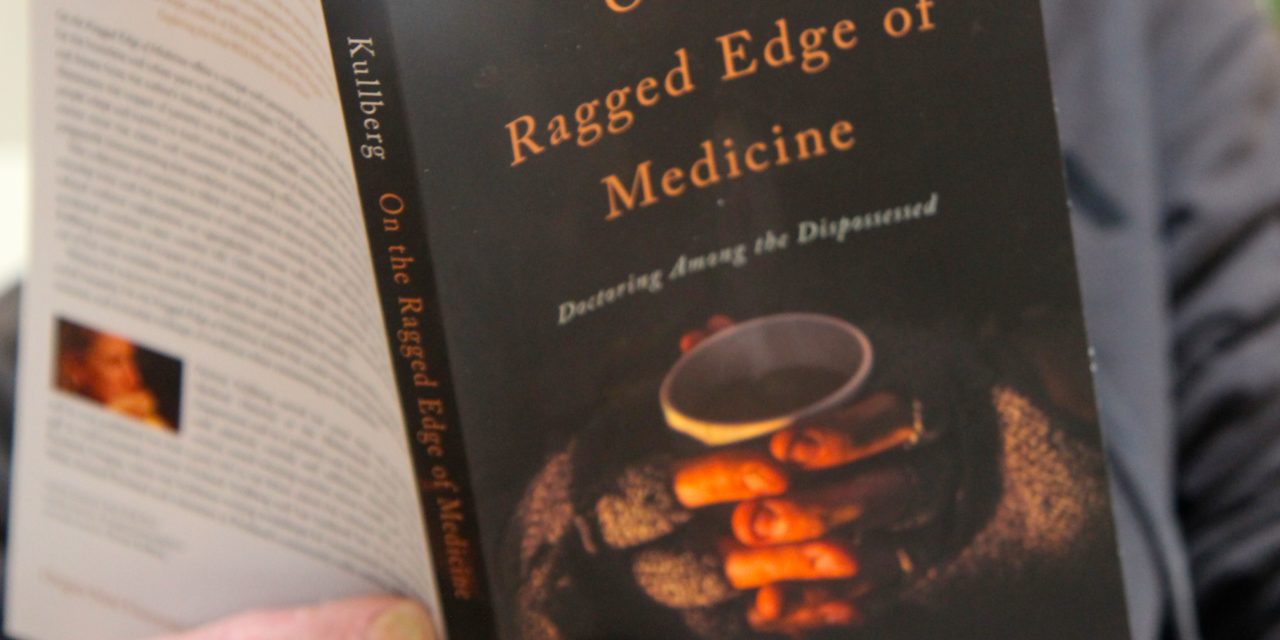

The Book

Title: On the Ragged Edge of Medicine: Doctoring Among the Dispossessed

Author: Patricia Kullberg

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis

Available locally: J Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway, Eugene (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

By the light of day they are everywhere, in pockets small and large. They are seen, and sometimes they are dodged. Mostly, they are ignored.

By night they scatter, in pockets small and tiny, the better to cloister themselves against the elements which include predators. At this time, they are not seen. They are forgotten.

They, the dispossessed among us, also are a stain on the soul of our society, with no end in sight. Their number – and the accompanying mental, physical and addiction disabilities that they wear in layers – keeps growing. There is no political or social will to fully cut to the heart of the individual stories or the collective, grinding fatalism that is the poverty these men and women live in. Worse, fewer men and women are engaged in the front lines in public health to fight and advocate for the dispossessed. Doctors, especially, are moving into specialty fields and greater money.

Literary reviewer Daniel Buckwalter; photo by Randi Bjornstad

All of this, along with poignant vignettes from her time on the front lines, is wonderfully (and often distressingly) chronicled in Patricia Kullberg’s “On the Ragged Edge of Medicine: Doctoring Among the Dispossessed.” Kullberg served for more than two decades as medical director at the Multnomah County (Oregon) Health Department, starting in 1988, and she served part-time as a primary care physician for persons living with physical, mental, and addiction disorders.

“These narratives are not about triumph and tragedy …. You won’t find too many happy endings here,” Kullberg writes in the preface.

She’s not kidding. From Pam to Jocelyn, from Joyce to Mindy, on to Barry and Scotty, Samuel, Harry and many more, Kullberg writes unsparingly about the rigors — the exhaustion — of public practice. She started her part-time practice at the Burnside Health Center, then moved to the Westside Health Center.

She also sees the grace in her former patients. “They amazed me. They were funny, insightful, and caring in the midst of destitution. They were resilient and incredibly resourceful. Not for a minute did I think I could endure what they did.”

Endure they did. There are stories of childhood abuses that never heal, war memories that never dim, drinking and illegal drug addiction, and psychosis and the mishmash of powerful narcotics that patients went to great lengths to get (as Joyce does for the drug Haldol). There are stories of personality disorders (“It is not something you have, it’s who you are”) and bodies prematurely eroding in the harsh day-to-day survival of street life.

All of this — the doctoring among the dispossessed — is done on shoestring budgets, because the government is of no help. Or if it does, the help is misguided. Of the original Oregon Health Plan, the mid-1990s brainchild of then-state senator and later governor John Kitzhaber, Kullberg writes that it introduced “the concept of feeding more people at the health-care table by thinning the soup.” And the current Affordable Care Act? A “poster child for half-measures,” she notes bluntly.

Of the patients that Kullberg chronicles, the one I cheer for the most (and wonder what happened to her) is Joyce, the woman who went to great lengths for her daily fill of Haldol. Haldol (haloperidol) is an antipsychotic used to treat paranoia and delusions of grandeur as well as visual and auditory hallucinations. It is, as Kullberg describes it, “a jackhammer of an antipsychotic.”

Joyce heard the voices — “They tell me to take a knife and cut my throat because I’m bad” — and she is afraid of large crowds and being touched. Joyce also takes the drug Cogentin (benztropine) to relieve side effects of the Haldol. But among Cogentin’s side effects is sedation. Joyce worries that if her level of Haldol is raised to fully stop the voices, the level of Cogentin also would have to be raised. That would make her too “stiff” to run from the predators that lurk at night, ready to pounce on a single homeless woman.

Joyce needs housing, but “shelter’s too crowded” or “room’s a lot of trouble.” Worse, the Burnside Health Center closes in the summer of 1996. Staff is transferred to Westside, five blocks away. Signs are posted everywhere declaring the news. Somehow Joyce either doesn’t read announcement or doesn’t compute it.

So Joyce went to emergency rooms throughout Portland, then hopped on Greyhound buses for ERs in Washington, Idaho and California, all in search of her daily fill of Haldol and Cogentin.

Two years pass.

Finally, she comes to the attention of a health care crisis center. It sees Joyce’s empty vials with Kullberg’s name of them. It arranges for Joyce to meet with Kullberg again, at Westside.

“She was somehow transformed, not hugely, but she possessed an additional jigger of confidence,” Kullberg writes. “Maybe the voices had trouble trailing her to all those exotic locales, across great rivers, deserts, and mountain passes in search of her Haldol.”

Then there’s this from Kullberg: “It was for me a grand reunion. I never saw her again.”

Why go into public medicine? Kullberg was in a private suburban practice, but she longed for something more. “I no longer felt quite at home in my own skin, among my own people, within the smug circles of privilege. So it was that some sense of duty and middle-class guilt propelled me to Burnside, motives that can render the heart impure — patronizing and paternalistic.”

However, she writes, “The patients saved me. They took me at face value, as a doctor who was interested and wanted to help. They commanded my affection and respect. They taught me humility.”

Why retire? I imagine there’s a shelf life to practicing this high-intensity form of medicine. Kullberg never says the word “burnout” in the Afterword to her book. It’s implied in the story she tells of a nameless patient whom she barely remembers except as a Caucasian male who spoke perfect English, “and that he was not difficult — not demanding, disjointed, dissembling, etc. He was a nice man. What I remember was my sudden remove from it. I was not interested in what the patient was telling me.”

It’s a revelation. “Then, without warning, here I was with this man, shrinking away from his words, thinking to myself, I don’t want to hear this. I don’t care about your problem. It was sobering.”

So Patricia Kullberg retired in 2011. Her DEA certification, her board certification and her license lapsed. Good for her, I say. But bad for us, because whether by the light of day or dark of night, the dispossessed among us grows in numbers, and their cases are more complex by the year. It is a stain on the soul of our society that needs to be removed with compassionate resolve.

We could use more people like Patricia Kullberg.