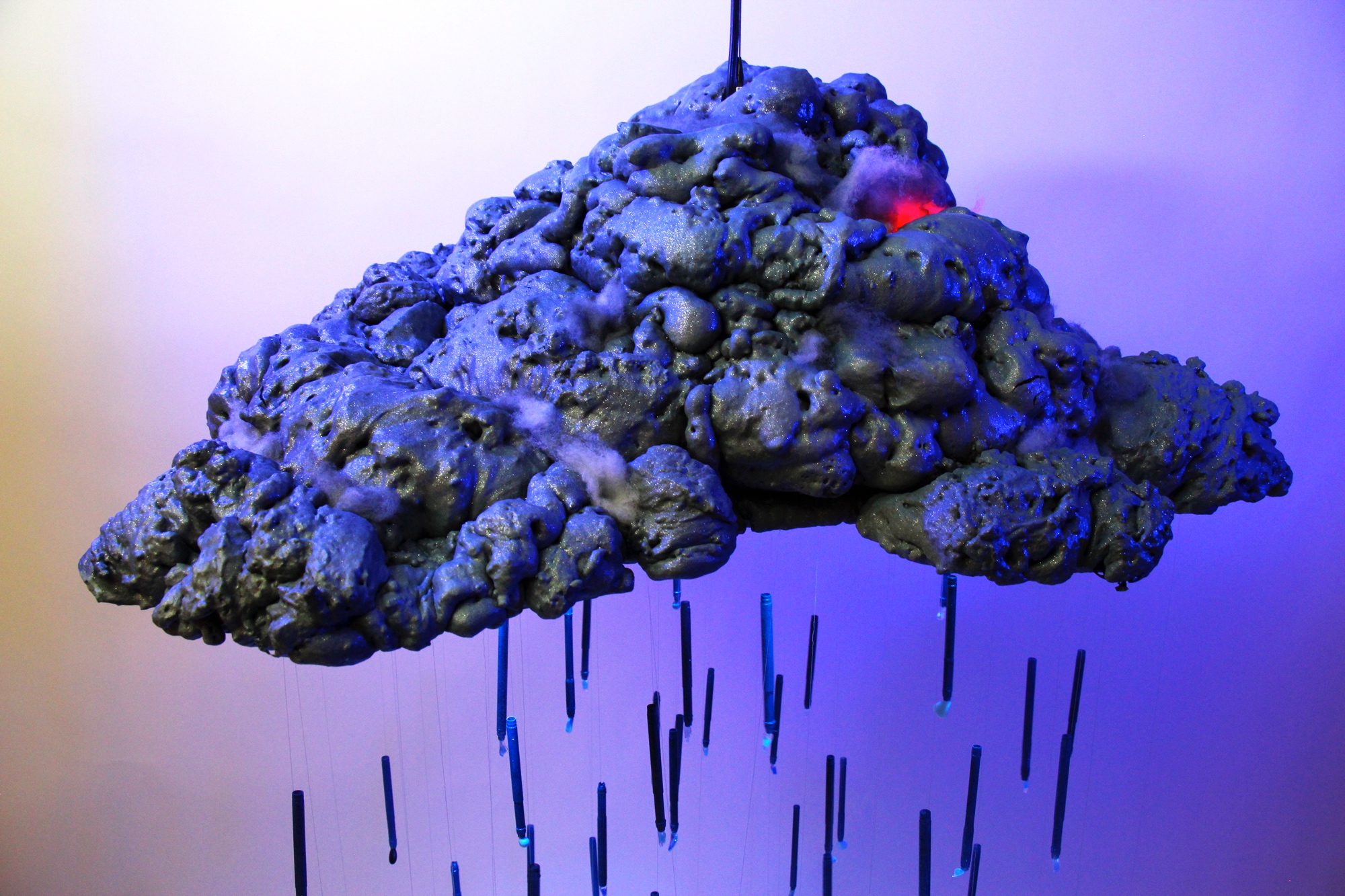

(Above: Tens of thousands of revelers such as this costumed performer turned out in Yantai, China, for a Chinese New Year celebration in 2019 at the ancient Yuhuang Temple; many such celebrations were curtailed or canceled in 2020 because of the coronavirus outbreak. Photos by Randi Bjornstad)

By Randi Bjornstad

One year ago, we — my photographer-husband Paul Carter and I — had just returned from almost three weeks in China, a stretch that included ushering in the Year of the Pig during the Chinese New Year, sometimes also known as the Spring Festival.

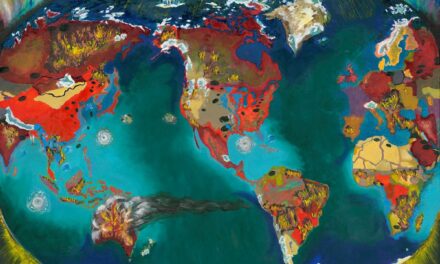

Last year’s star of the Chinese zodiac was the pig. The lineup includes rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig

This year, of course, has been vastly different. Instead of many millions of Chinese people crowding trains, planes, and automobiles in the annual trek to return to their hometowns and families and welcome in the Year of the Rat, the onslaught of a new and vicious form of coronavirus — now dubbed Codiv-19 — pretty much put a stop to all elements of the usual joyous parades, fireworks, visitations, and feasting.

The observation of the Chinese New Year lasts 15 days, and because it’s set based on the lunar calendar, those dates change. In 2019, the festivities culminated on Feb. 5, compared with Jan. 25 this year.

Vast distances, packed trains

In the run-up to last year’s trip, we actually had to adjust some of our travel plans because of the crush of the season. For example, instead of traveling great distances from Yantai, the city where we stayed with friends on China’s east-central coast in Shandong province, we opted to stay in Shandong and check out its historic and artistic offerings, which are many.

When we first planned the trip, one of the must-see things on my list was the Terracotta Army. That’s the site of a spectacular archeological dig where the first emperor of unified China, Qin Shi Huang (the letter “q” is pronounced “ch” in Mandarin), ordered the creation of an entire clay army, complete with soldiers and horses, to protect him in the afterlife.

However, it’s 1358 kilometers (nearly 850 miles) between Yantai and Xi’an (“x” is pronounced “sh” in Mandarin). That’s a significant train ride in ordinary times, but because of the holiday, tickets were hard to come by, and even China’s fabled on-time trains often were running late.

An excavation related to the “chariot wars” of 200 B.C. includes chariots, horses, and even charioteers buried after battle

As luck would have it, it turned out that Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s armies also had spent considerable time in Shandong province during the period when he was fighting to unify China in what’s sometimes called the chariot wars.

In a museum there, instead of the pottery army there’s a large area just now being excavated that holds actual buried chariots, chariot horses, and even sometimes their charioteers who either lost their lives or, some believe, were sacrifices or even buried alive to serve as escorts for dignitaries as they left this life for the next.

The museum also has a fascinating display of recreated vehicles from that ancient era, ranging from some used to scale the walls of fortified cities to everyday farming vehicles to elaborate conveyances for the elite.

It was a bitterly cold day when we were there, but it was nonetheless rewarding to see firsthand that slice of ancient history. Later the same day, though, we stopped by another place in the countryside where there is supposed to be a remnant of the Great Wall of China on view, but it was closed for the two weeks of new year revelry.

A combination coffee shop, bookstore, and art gallery in Qingdao’s historic German section offers intriguing artwork for sale, above left and right

Another result of traveling at that time meant flying not into the much more crowded Beijing but into Qingdao, a lovely, smaller city (9 million people compared with Beijing’s 21.5 million).

Qingdao is fascinating, a naval port located on the Yellow Sea. It was occupied by Germany from 1898 to 1914, and then by Japan from 1914 to 1938. There’s an area near the water that still has many buildings from the German era. The city also boasts a robust beer industry (Tsingtao beer comes from there) and even hosts an international beer festival.

Landing in Qingdao was great also because it put us much closer to our Yantai destination, just a 90-minute ride on a bullet train compared with six hours from Beijing. We stayed a night in a hotel right on the waterfront before continuing on to Yantai.

This coffee/tea shop, with its artwork and books, felt as familiar as if it had been in Oregon

Just diagonally across the street from our hotel on the waterfront in Qingdao’s German section, there was a interesting-looking clock museum (unfortunately closed during the holiday period) and a lovely combination coffee/tea house, book shop and art gallery replete with interesting and tempting pieces that unfortunately couldn’t fit in our luggage, which consisted of one carry-on each.

Land of contrasts

In Yantai, population 6.5 million, we stayed with friends who live on the 14th floor of an 18-story highrise apartment building like the many that dot the skyline of virtually every larger city. That kind of  density is how China manages to concentrate its 1.4 billion people in areas that still allow for vast stretches of farmlands and tiny villages. Despite its size, it took no longer than 20 minutes to get out of Yantai into the countryside by car for a sunny afternoon jaunt that included an invitation into the home of an elderly man (left) whom we saw along the way. He proudly showed us his kang, a sleeping platform with water pipes running underneath that, heated by a woodstove, keeps old rural houses livable in the winter.

density is how China manages to concentrate its 1.4 billion people in areas that still allow for vast stretches of farmlands and tiny villages. Despite its size, it took no longer than 20 minutes to get out of Yantai into the countryside by car for a sunny afternoon jaunt that included an invitation into the home of an elderly man (left) whom we saw along the way. He proudly showed us his kang, a sleeping platform with water pipes running underneath that, heated by a woodstove, keeps old rural houses livable in the winter.

Trays of silkworms in an open air market in Yantai; in addition to providing silk thread, the worms are a staple food in China

Naturally, food was a centerpiece of every day, and we frequently accompanied our hosts to an upscale supermarket in a nearby mall and also several times to an outdoor “wet” market similar in form to the ones suspected of helping to spread the recent coronavirus mutation.

Farmers truck live animals in from long distances — and butcher them right there on the street — to sell meat to dense throngs of passing shoppers. There were chickens and hogs and tank upon tank of various kinds of fish and shellfish. There were vast trays of silkworms, to be cooked and then eaten by crunching them between the teeth and spitting out the shells before swallowing the soft “meat” inside.

Dumplings, always a popular food in China, are a necessity during Chinese New Year and take hours to prepare

If there’s one food that’s synonymous with the lunar new year, it’s dumplings. Virtually every household either makes its own or lays in a supply for drop-in well-wishers. Our hostess — her Chinese name is Yuchai but we know her by Star, an Americanized moniker bestowed by her American husband, longtime Lane County commissioner and China enthusiast Jerry Rust — spent hours preparing hers, assisted by her daughter Chen Chen and granddaughter Jiang Jiang (pictured at left).

In Yantai, because of its location on the coast, the staple protein is fish and shellfish, served at nearly every meal, baked or poached and bathed in a savory sauce.

Fish are sometimes presented as sculpture, deep-fried in lifelike swimming positions

Sometimes the fish even takes on an aspect of art, as at one restaurant meal in which it was formed into a vertical shape and deep-fried to give it a sculptural presentation.

On one drive into the countryside, we stopped for lunch at a noodle shop in a small town. The noodles were made by hand in a kitchen right off the dining area, where diners can watch the mixing, stretching, cutting and boiling of the noodles before they are served.

Our hosts quickly learned that the restaurant had been open for only a week, and that the proprietors were three generations of a Muslim family — grandparents, parents, and two adorable little boys — who had recently moved to Shandong from far northwest China. In retrospect, after later news coverage about the treatment of Uighurs in China, we have to wonder if they might have relocated for cultural reasons and how they have fared in their new home.

In any case, their noodle soup was delicious.

Chinese New Year

The Yuhuang Temple in Yantei has room after room filled with brilliantly colored statuary representing various lords and deities

A few days before the official New Year celebration, we visited the Yuhuang Temple simply to wander among the buildings with their beautiful architecture, gardens, and statuary. Despite its location in the middle of the crowded, bustling city, the temple grounds were nearly deserted, with just a few people lighting incense sticks or dropping to their knees onto thick brocade pillows to offer prayers before ancient Chinese gods.

The original temple dates to the Yuan Dynasty, which was in power from 1280-1368 A.D. and expanded and rejuvenated during the following Ming (1368-1644 A.D.) and Qing (1644-1911 A.D.) dynasties.

Tens of thousands of revelers gathered at the Yuhuang Temple to celebrate the Lunar New Year in Yantai, China, in February 2019

Through the centuries, the compound has become an important part of Yantai’s Chinese New Year celebration, and on the day of the official festival, it was packed with many thousands of people, buying food and trinkets from hundreds of vendors and watching performances that included music, dancing, and brightly costumed actors depicting Chinese history and fables.

It soon became obvious to us that we were among the curiosities of the day at the Yuhuang Temple. We didn’t see any other Westerners among the huge crowd, and many people wanted to stare at us, offer greetings, and take our pictures. A television crew with a female reporter who spoke English fluently even asked if they could

Fireworks fill the skies every night for a week leading up to the Chinese New year holiday; this photo was taken from a 14th-floor apartment window

interview us. Later, we learned that our pictures had appeared in a local newspaper as part of its Chinese New Year’s coverage.

In addition to public activities, at night the sky is lit and the air filled with noise and smoke from millions of fireworks as people come out of their homes to set off elaborate displays. Even on the 14th floor of the apartment tower, fireworks flew by or detonated right outside the windows every night for a week as the holiday frenzy grew more intense.

It’s hard to imagine now how much different Chinese New Year was in 2020 compared with the joyous crowds, smiling faces, and sensory-overloaded sights and sounds we experienced just a year ago.

Nonetheless, we wish the people we met in China a Happy New Year — one of the helpful phrases we used often during our trip, xin nian kwai le — and hope to see them again under more pleasant circumstances.