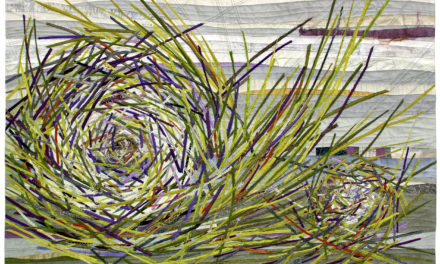

(Above: Detail from Nocturnal Life of Trees, one of artist Claire Burbridge’s works on display at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in a show called Pathways to the Invisible)

By Randi Bjornstad

The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon is chock full of interesting exhibits, but two new shows by women artists merit special — albeit dramatically opposite — attention.

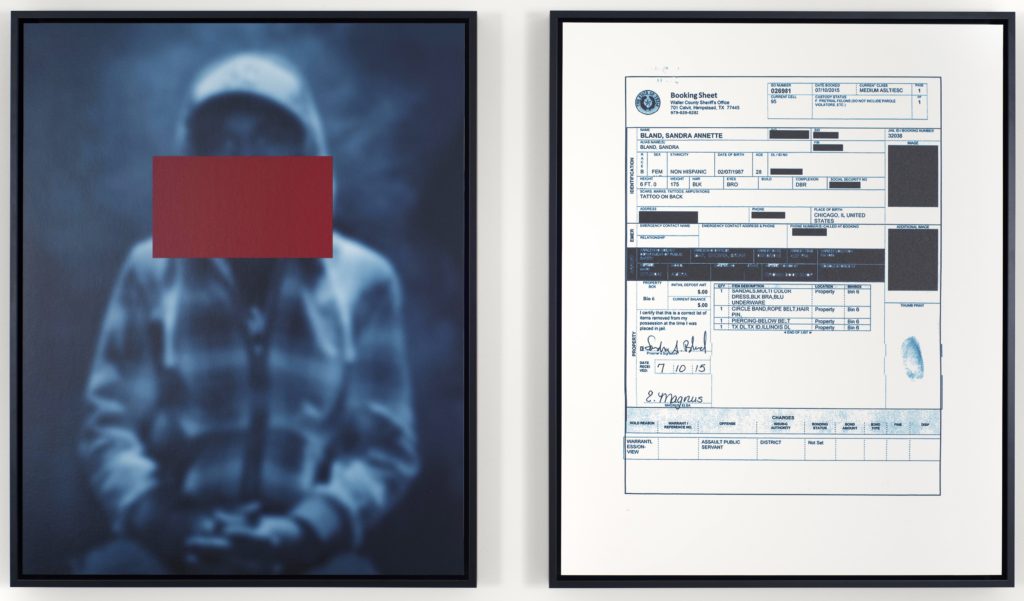

The figures in Weems’ The Usual Suspects are indistinct, as if each represents many

One is a series of photographs taken by Portland-born Carrie Mae Weems and titled The Usual Suspects, which examines what has become a tragically predictable experience in which Black people — men, women, and children — have lost their lives at the hands of law enforcement officers. The photographs are deliberately blurred, “making you want to see these people more clearly, but you can’t,” communications manager Debbie Williamson Smith said. “But that was her purpose, to raise the question, ‘How do you measure the value of life?’ “

The exhibit includes thumbnail sketches from police logs that offer a bare-bones description of the fatal encounters but almost always end, “To date, no one has been charged in the matter.”

Seed Heads, one of Claire Burbridge’s nature studies in pigment pencil on black paper

In contrast, Claire Burbridge: Pathways to the Invisible, focuses on the British-born artist’s attention to the exquisitely minute detail found in nature, from leaves and mosses to insects and bird nests that she re-imagines in the form of drawings, prints, wallpaper, or simply carries home as found objects.

“She started out as a sculptor and then turned to creating new worlds based on what she discovered during her own treks in nature,” Williamson Smith said. “Her work has layer upon layer of detail, but if you search, you can see all of the elements very clearly.”

Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems; photo courtesy of Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

Born in 1953 in Portland, Weems was one of seven children. Her first foray into the arts was in dance and street theater as a teenager before relocating to San Francisco to study modern dance. While there, Weems decided to pursue further education at the California Institute of the Arts, at the same time she also was becoming politically active as a union organizer.

During her long career, Weems has done a variety of projects, including public art, video, and many photographic collections. One of her best known is the Kitchen Table Series, in which she created portraits of family members gathered at their kitchen tables, and From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, a collection of photographs that maps the breadth of African American history.

In 2013, Weems was one of the recipients of the MacArthur “genius grant” awards, one of dozens of prestigious recognitions through her decades of work. She turns 67 years old this April 20. Also possibly in April, she will receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Oregon for her contribution to the study and elucidation of the African American experience.

Her show, The Usual Suspects, is on display at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art through May 3.

Claire Burbridge

Clair Burbridge; photo by Randi Bjornstad

Originally from London, England, and raised in Scotland and the county of Somerset, Burbridge now lives in Ashland, having turned from her original emphasis on sculpture to creating layered artistic worlds based on objects she observes or gathers on her many walks in nature.

“I started drawing insects when I came to Oregon — we don’t really have that many in England,” Burbridge said. “I am quite obsessive about detail, so insects, plants, and other objects I find as I go along all are things I like to incorporate in my art.”

She was an artist even as a child. “I had a lot of sketchbooks, and I brought in a lot of stuff for drawing,” she said. “My dad is an engineer — he wanted to be a ballet dancer when he was young — and my mother is very artistic, although she chose to study law.”

Burbridge was the second-born of twins. “My mother was not even aware that there were two of us,” she said. “After my brother was born, the doctors said, ‘There are some additional limbs here.’ I think as a result he took all the responsibility for things, being older, and I was just allowed to do whatever I wanted.”

She relocated to the United States after she found a soulmate in Matthew Picton, whose art involves intricate paper sculptures that reflect architectural, historical, and geographic topics. The couple married nine years ago.

“Moving to a different culture and experiencing all the aspects of that has been very inspiring,” Burbridge said. “Everything changed dramatically, but I feel that is where this new burst of creativity has come from.”

Her show, Pathways to the Invisible, is on display through April 19.

All the Boys is one of Carrie Mae Weems’ set of photos in a show called The Usual Suspects that examines the loss of Black lives in modern America