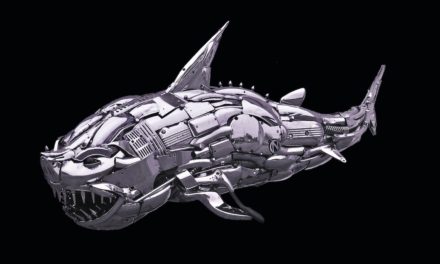

(Above: Port-Hole Slab Series, #10 by Rick Crawford, 2021; created from maple burl and steel, with paintings by Alana Garrigues’ paintings in the background. Photo by Jordan Essoe.)

By Jordan Essoe

He was a painter and she was a pianist.

They were married for 42 years. They didn’t have children, but they had many friends in church, the Kiwanis Club, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and other social groups.

They held a weekly life-drawing session in their home basement and hosted an annual Thanksgiving dinner nicknamed “the orphan party,” where anyone was welcome. They dreamed of creating communal space on a more permanent basis. They wanted to throw open the doors of their home to give Manzanita a place where friends and neighbors could always gather, learn, and create.

These are among the things people remember about Lloyd and Myrtle Hoffman. Many who knew them personally have moved away or died, but a dedicated group of local volunteers continues to fulfill the couple’s wish for a full-fledged community art center in Manzanita, a petite oceanside town located between Tillamook and Cannon Beach.

“Since the beginning, the North Coast has always been a haven for artists, but they were missing a central gathering place,” David Dillon, a founding board member of the Hoffman Center for the Arts, said. “We established ourselves and the community embraced us.”

Eighteen years after Myrtle’s death, the Hoffman Center is a lodestar of cultural life for locals and tourists, and serves the same role for surrounding areas north to Wheeler and south to Tillamook.

The path to the center’s formation didn’t always proceed exactly as imagined. The Hoffmans’ modest, beloved home on the corner of Laneda Avenue and Division Street is gone, demolished and hauled away. Yet the road to actualizing the Hoffman Center did not detour sharply. Standing today in the spot where the Hoffmans’ house used to rest, you can see the art center established in their name. It’s right across the street.

The exterior of The Hoffman Center for the Arts today. Photo by Jordan Essoe

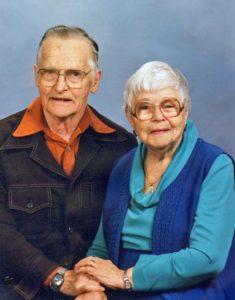

This coastal Oregon community is far removed from Lloyd Hoffman’s 1908 birthplace of Lake Bronson, Minn., a town small enough to make Manzanita’s population of 400 look crowded. Myrtle was born in 1910 in Portland, where they both grew up. For livelihood, he was a professional sign painter and she was a secretary. Shortly after they retired in 1973, they left the city for the beach, where for the next 24 years they would refocus their lives on friends, art, and each other.

In 1999, the Hoffmans moved together a final time, just a little over a mile away, into an assisted care facility in the neighboring town of Nehalem. Lloyd died six months later. He was 91. In 2004, at age 94, Myrtle followed. She had been a widow for four and a half years and had no living relatives. When friends visited her in her final days, often the first thing she said was, “I miss him so much.”

Lloyd and Myrtle Hoffman, ca. 1992

“We should all have that level of love,” Dillon said.

In a sense, a steady reiteration of that love keeps the Hoffman Center’s mission alive: The center reflects both the love between Lloyd and Myrtle and their love for a tangible experience of community.

The Hoffmans left behind their home, $197,000 in cash assets, and the enduring ambition to use those two things to create a center to support and further the arts. The Hoffman estate’s trustee recruited a group of local advisers that reads like a small-town jury in a stage play — the newspaper editor, the vicar of the Episcopal church, a civil engineer, a librarian, a retired lawyer, a shop owner, and two artists. By late 2004, the group formed a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization to take custody of the money and property and put initial ideas into motion. They subdivided most of the house into for-rent artist studios and maintained the weekly life-drawing sessions the Hoffmans had hosted for decades.

The original Hoffman home shortly before demolition; photo by David Dillon (2014)

The Hoffman home was problematic. The rooms were too small for public events, and the condition of the property wasn’t great. Parking was an issue. Hoffman board members researched and visited other art centers and were inspired by what they discovered, but unfortunately almost none of the ideas that excited them could be realized with what they had back in Manzanita. It was difficult to admit, but they needed a different building. On an emotional level, this seemed partially to violate the spirit of the Hoffmans’ wishes. On a practical level, there wasn’t enough money to build from scratch or purchase a new property.

Neighboring the Hoffmans’ lot is the Manzanita Library, built in 1986 on land that in part was donated to them by the Hoffmans, who gave up a quarter of their property so the library could have a parking lot. The North Tillamook Library Friends also used the Hoffmans’ garage to store and sort book donations. The Hoffmans had always seen the library as an essential part of the overall vision for their future art center, but when the Hoffman board explored the possibility of merging with the Manzanita Library, the library board voted against it.

Across Laneda Avenue was an eccentric gift shop called the Treasure Cave where tiny aisles overflowed with cheap souvenirs, toys, and trinkets. Part of its oddity came from the building’s origin as a mini-storage facility. Much of its compartmentalized structure remained, including several original roll-up doors. Individual storage units had been used over the years for a massage parlor, a management office of short-term rentals, and other miscellaneous businesses. A couple of units were still full of the abandoned belongings of forgotten tenants.

Maybe it was a junk shop or maybe it was dormant destiny. The building was promising, because it was in good shape and had two relatively large main rooms. In 2006, the Hoffman board approached the Treasure Cave’s owner with an offer. The possibility of remaining in such tight proximity with the Hoffman home and Manzanita Library was appealing, and the board was willing to use almost all the cash they had to make a down payment. Nearly with a shrug, the owner of the Treasure Cave agreed, and the Hoffman Center gained a new address.

“That original group of board members could have given up. It was an enormous amount of effort to accomplish this,” current Hoffman board president and interim gallery manager Mary Roberts said.

For the first time, the center shouldered a mortgage. They needed more revenue, but to fund-raise effectively they had to demonstrate broader engagement with the community. The central room in the new building could hold about 80 people, and they immediately started organizing educational lectures on a wide range of cultural and historical topics. They also put on concerts, book readings, film screenings, and offered classes in writing, painting, mosaics, textiles, ceramics, and more. If an event required more space, they moved the program offsite to the Pine Grove Community Center (which had previously housed the library) or St. Catherine’s Episcopal Church.

In 2007, original board member and artist Kathleen Ryan spearheaded a project to transform one-third of the new location’s 3,000-square-foot interior into a comprehensive clay studio. Though not a ceramicist, Ryan saw the potential for converting the partitioned mini-storage spaces in the back of the building into rooms dedicated to glazing and for equipment such as slab rollers and kilns.

“Most people cannot afford that equipment, so this is a huge service to the community,” said Roberts, who started off as a volunteer in the clay studio and has many of her own ceramic works exhibited on a stand outside the administrative office.

The center also began using the front room as an active gallery space, exhibiting the work of locals or other artists who were in some way meaningfully connected to the North Oregon Coast.

Things were going well at the space they referred to back then as “The Annex.” But the Hoffmans’ house was falling apart.

It was always cold and wet. It leaked constantly. There was a big crack in the main beam. Fixing all the structural and cosmetic problems seemed impossible if there was going to be a budget for pursuing the institution’s long-term goals. In 2014, with reluctance, the rented art studios were closed, the life-drawing sessions were relocated, and the Hoffman Center’s board voted to bulldoze the house. Residents donated $15,000 to ensure the demolition was completed before the 4th of July parade.

As the backhoe felled the home, a group of board members, artists, volunteers, and others watched with mixed emotions. It must have been a relief to be rid of the interminable maintenance problems, but surely some guilt accompanied the sight of bedrooms and social rooms, replete with family and community history and foreclosed potential, being reduced to rubble. In a moment of levity, an art model remarked, “Whatever you replace it with, when you restart the life-drawing classes, I hope you make it warmer.”

Within a few weeks, the Hoffman lot was reclaimed as a garden. A local landscape designer and a team of volunteers arranged clusters of donated plants within a carpet of gravel. It has since evolved into a horticultural demonstration project designed by National Public Radio journalist and botany expert Ketzel Levine, and the garden focuses on indigenous plants that are hardy enough to thrive in the cold salty climate (including Manzanita’s namesake shrub). An outdoor classroom was installed in the back, where Levine intermittently organizes seminars. A small memorial space was added to honor Kathleen Ryan, who died in 2016 of cancer.

Today, the Hoffman Center focuses on five primary programs: visual arts, writing, horticulture, ceramics, and gallery exhibitions. “People now move here specifically because there is an art center,” Roberts said, including herself among them. “We love that. The space invites people to explore art and practice art. We strive to elevate the artist.”

They have nearly 100 volunteers, receive donations from households of every size, and in 2022 are looking to hire their first full-time executive director. To manage the gallery’s programming, a committee curates exhibitions from work solicited though open submissions. The submission window lasts for six weeks, once a year, and they accept proposals from any artist with North Oregon Coast connections.

For the March 2022 exhibition, the curatorial committee grouped together three artists who tidily mesh with one another, materially and aesthetically. The formality of Susan Walsh’s row of cabinets inversely answers the organic abstractions of Rick Crawford’s wood sculptures that in turn directly echo Alana Garrigues’ mixed-media paintings of tree rings. Throughout the show, a prevailing theme of reclamation and reuse heightens the individual potency of everyone’s work – but it also invokes the character of the Hoffman Center itself, which has repeatedly aroused its own identity and energy from a patchwork of resident legacy.

Walsh is a sign maker who worked to some extent under the tutelage of Lloyd Hoffman. The two used to meet up at Hoffman’s home shop to share work and ideas and the combined decades of woodworking experience.

Some of the old-growth redwood Walsh used in her artwork came from an estate sale of yet another sign maker, and she previously used some of that same wood to make signs for local clients, including the Manzanita Visitors Center. She has participated in Hoffman group exhibitions in the past, but this is the first time she has exhibited a full body of work in their gallery.

Wing cabinet (2021)by Susan Walsh, made of Douglas fir; photo by Jordan Essoe

Her wood cabinets, which she calls Reliquaries, represent a kind of bridge between sculpture and furniture. Inside each is a single focal object she found on Manzanita beach. Four cabinets contain pretty, white bird skulls and one has a wing. The cabinets are closed when you encounter them on the gallery wall, and it is through the act of opening the door that the inside becomes occupied – not just through the discovery of what Walsh has placed inside, but through the confrontation with one’s own expectations of use, storage, secrets, and keepsakes.

Walsh was motivated to make her newest cabinets in part after reading Richard Powers’ novel, The Overstory, which features a giant redwood tree as one of the main characters and tells the story of the people trying to protect it from being cut down by loggers. Exhibition mate Garrigues’ new work was inspired by the same book. When looking at her paintings and drawings, one might think of this passage from the novel where Powers writes from the tree’s point of view: “All the ways you imagine us… are always amputations.”

To Remember What Might Have Been, acrylic and acrylic ink on Douglas Fir by Alana Garrigues (2019); photo by Jordan Essoe

Intricately detailing the lyrical patterns of a tree trunk’s interior anatomy, Garrigues wants to imagine and map the life lines of trees that were never allowed to reach maturity. As a kind of palmistry for the missing years of dead landscapes, the artworks immediately summon the images of the countless serialized stumps and woodland graveyards one will encounter when driving from Portland to Manzanita.

For her largest pieces, Garrigues repurposed plywood that used to be part of her sister’s home. She is interested not only in the family provenance of that wood, but also its relationship to the timber industry and the fact that plywood is typically harvested from trees no older than 30 to 35 years.

“Really what I’m interested in is the stories that these trees can carry,” Garrigues said. “You can see not only the age of the trees through the rings, but also the quality of the soil and the water or if there were fires in the area – all of this information that the trees hold onto.”

Crawford has a similar fixation on the textures that the bodies of trees produce. He has been making art from scrap wood cut-offs for a long time, and prides himself on the fact that he never buys anything he doesn’t have to.

“All my work is repurposed materials,” he said. “I’m a staunch environmentalist, and the concept of waste just drives me nuts. I reuse what is normally cast off.”

For his new Port-Hole Slab series, Crawford worked largely from discarded post pieces and header beams removed from the historic Riverwalk in Astoria during restoration work. As a carver, he collaborates with the grain and growth rings of the wood and models the finished shape to show off the bewitching corrugation of those tissues. He bores an oculus in each piece, sometimes directly in the center, often punching out the pit to create it.

Crawford’s use of the oculus references something called a porthole slab, an access hole to an ancient burial tomb. Once the viewer understands this, the harmless and playful abstraction of the sculptures begins to sink beneath a thickening awareness of the surrounding space – seen and unseen – behind and beyond them.

“I’m not a religious person, but I do believe that energy is neither created nor destroyed, it is just reused,” Crawford said.

Crawford has been participating in programs at the Hoffman Center regularly since around 2016. He’s been included in their annual community show, typically scheduled in January, and had artwork featured twice in their publication, The North Coast Squid, A Journal of Local Writing.

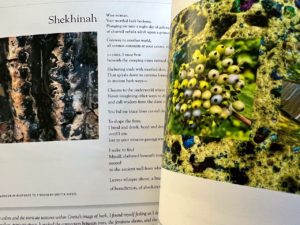

The Hoffman center’s other key publication is a bi-annual project called Word & Image, for which Crawford has been selected three times, and served once as a judge.

“With Word & Image, artists and writers are invited to submit three pieces of artwork or three pieces of prose to be juried in. And then they do a match-up,” he said. “12 artists matched to 12 writers.”

Selected visual artists are asked to create new work prompted by poetry or prose from the writer they’ve been paired with, and vice versa. It’s another strategy for repurposing material, to make a connection between two previously unconnected things, and leverage the shape of something new against the shape of something known. The project began in 2016, and the 2022 issue will be the sixth edition. Submissions will be open during April, and all Oregon coastal writers and artists may apply.

Interior pages from Word & Image 2020; photo by Jordan Essoe

Other upcoming projects include an exhibit called Capturing Oregon’s Magic, featuring a selection of realist, impressionist, and abstract paintings from the 19th century to the 1950s, many of them painted in Manzanita. The exhibit is curated by Bonnie Laing-Malcolmson, previously the Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Curator of Northwest Art at the Portland Art Museum, and selected from work featured in the book Oregon Painters, Landscape to Modernism, 1859-1959 by Ginny Allen and Jody Klevit.

The Hoffman Center is the only place the collection will be exhibited, and the high profile of the project represents an exciting new step for its programming.

“We’re almost back in battery, as we used to say in the Navy,” Dillon said, referencing the fact that they were largely closed for the bulk of the pandemic.

Dreaming of the more distant future, he added, “And someday we’ll even have a nice new building on the main lot.” He paused. “That’s down the line a little, though.”

Plans for new construction on the site of the previous Hoffman home may be on the back burner for now, but it is poetically inviting to imagine once again reclaiming and reinventing that space and seducing the ghosts of its previous history back inside for another round.

Hopefully, they’ll finally bring back Lloyd and Myrtle’s life-drawing class — as long as they keep that promise to make the room a little warmer.

Oregon Painters, Landscape to Modernism, 1859-1959, by Ginny Allen and Jody Klevit, 2nd edition (2021, Oregon State University Press).