(Above: Border detail from a Rome Baroque tapestry, part of “The Barberini Tapestries,” an exhibit at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

By Randi Bjornstad

In a word, “Wow.”

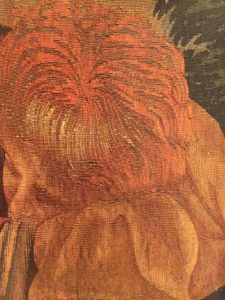

17th-century Barberini tapestry detail

Not as elegant as “sensational” or “spectacular” maybe, but it aptly describes the coming to Eugene of 10 panels of “The Barberini Tapestries,” an exhibit that opens on Sept. 23 in the Throne Room at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on the University Oregon campus.

A public reception will take place on Sept. 22.

Several facts make this show not only important, but also a bit breathtaking. The tapestries began as a collection of 12 pictorial textiles depicting the Life of Christ, originally commissioned in 1643 during Rome’s Baroque era by Cardinal Francesco Barberini — a member of an ancient and important Tuscan family that also included his uncle, Pope Urban VIII — and woven in a family “manufactory” of which he also was the primary patron.

They remained for centuries in Europe, either on display — reportedly including at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome — or stored away for safekeeping once the tapestry craze there subsided in favor of other art forms. By the late 19th century, often called “the gilded age,” fine art of many kinds had caught the fancy of wealthy Americans eager to display their wealth by creating their own impressive collections.

One, an erudite and shrewd American named Charles Mather Ffoulke, had made his fortune in wool and mining. He took a two-year sabbatical from his business to spend the time in Europe studying tapestry and master paintings.

Because of his interest in wool, the tapestries became his passion, and when Ffoulke returned to Europe on a later trip that culminated in 1889, he negotiated the purchase of 135 woven panels from the Barberini family collection.

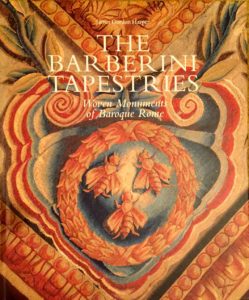

UO art history professor James Harper wrote the book that accompanies the exhibit “The Barberini Tapestries,” at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the UO

According to a book that accompanies the UO exhibit, written by UO art history professor James Gordon Harper — who is credited with bringing the tapestries to Eugene — Ffoulke really didn’t want that many.

At the time, Harper writes in “The Barberini Tapestries: Woven Monuments of Baroque Rome,” the New York Times reported that “When the tapestries of the Barberini Princes in Rome were for sale (Ffoulke) tried to purchase certain ones, but, finding that in order to obtain those he wanted he must take all, he purchased the entire collection.”

That included the Life of Christ panels, which Ffoulke soon sold to a rich New York heiress, Elizabeth Underhill Coles, who had no intention of displaying them herself. However, being Episcopalian (although also having descended from some of the earliest Quakers in America), she pledged the tapestries to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on New York’s Upper West Side, then in the planning stages. Construction of the huge Romanesque-Byzantine and Neo-Gothic structure began in 1892, after Coles’ death, and like the construction time for many cathedrals still has not been completed, although services have been conducted there since 1899.

Because of the vagaries of construction, the entire collection of panels was not installed at St. John the Divine until 1911. First they remained in storage for years, with one or two being taken out at a time for display. In 1907, the entire set went on display at the Metropolitan Museum of art, with the understanding that they would be moved to their ultimate destination in the cathedral when it was able to accommodate them properly.

Then, just before Christmas in 2001, a an electrical fire started in the cathedral’s gift shop, gutting it and causing smoke damage in varying degrees to the entire interior of the building.

Two of the Barberini panels — The Last Supper and The Resurrection, which are not included in the UO exhibit — hung closest to the origin of the fire and received severe damage but have been partially restored. The rest have been cleaned and refurbished.

The cathedral was rededicated, with the Barberini panels, in 2008.

Tapestry as Art

As art goes, the Barberini panels are huge. Each measures nearly 16 feet tall, with widths ranging from 12 feet to 19 feet.

“The Agony in the Garden,” one of 10 panels that makes up the Life of Christ exhibit at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

As Harper describes them, there are two ways to view the massive tapestries. One is to look at the “stories” they tell. The other is to study the social and political history they reveal within their intricately woven borders, in terms of family symbols such as coats of arms, allegorical figures depicting Faith, Hope and Charity, even homages to ancient Greco-Roman mythology.

The panels in the UO exhibit begin with The Annunciation, in which the angel Gabriel appears to an ordinary woman, a virgin named Mary, to inform her that she will bear a child who is the Son of God.

It is followed by The Nativity, or the Adoration of the Shepherds, depicting the visitation by local sheepherders to the barn where Mary and Joseph, who could not find a room in Bethlehem, repaired and where she gave birth to Jesus.

The Adoration of the Magi, also called the three kings or the wise men, is next, showing them visiting the holy child and presenting their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

The remaining panels in the series include The Baptism of Christ, The Consignment of the Keys to St. Peter, The Transfiguration, The Last Supper (not on display), The Agony in the Garden, The Crucifixion, The Resurrection (not on display), along with Rest on the Flight into Egypt and Map of the Holy Land.

A detail from a Barberini tapestry dating to the 17th century

At the time that Cardinal Barberini became interested in tapestries, the craft in Italy for the most part had been dormant since the 15th century, according to Harper’s book. So he began a systematic study of the process, contacting people all over Europe — without benefit of the Internet, text messaging or telephone — and gathering samples of wool, cloth and thread used in other places.

He relied in part on an architect, Luigi Arrigucci, who provided information about the Medici family’s tapestry works, which procured its wool from the Provence region of France, where the oil content of the wool was ideal for dyeing colors successfully.

Interestingly, Harper writes that “one of Barberini’s preferred research methods was to send out questionnaires” and that three of those, “annotated and returned by Nicolás Enriquez de Herrera, Giovanni Francesco Guidi di Bagno, and Fabio de Lagonissa, survive.”

Those three, among others, advised him about wools, soaps, oils, spinning techniques, pigments, water for dyeing and “sources and prices for key materials.”

The Barberini Tapestries: Woven Monuments of Baroque Rome

What: An exhibit of the Life of Christ tapestries commissioned in 1643 by Cardinal Francesco Barberini and now owned by the St. John the Divine Episcopal Cathedral in New York City

When: Opens Sept. 23; free public reception on Sept. 22 from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m.

Where: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, 1430 Johnson Lane, University of Oregon campus

Special events:

- Oct. 1 — 2 p.m., gallery tour with curator James Harper, UO art history professor and author of “The Barberini Tapestries: Woven Monuments of Baroque Rome”

- Oct. 4 — 5:30 p.m. textile expert Nancy Arthur Hoskins discusses the tapestries of Coptic Egypt (late-third to mid-seventh century AD)

- Oct. 11 — 5:30 p.m., “Reading, Writing and Collecting in Baroque Rome” with UO association professor Nathalie Hester, talking about literary production during the time of Cardinal Barberini

- Oct. 13 — 12:30 p.m., UO graduate students Holly Roberts and Alison Kaufman perform 17th-century Italian instrumental and vocal music; free

- Nov. 16 — 4:30 p.m., David Rogers explores lute and theorbo repertoire of baroque composer Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger, house musician to Barberini

- Nov. 16-17 — International experts on 17th-century tapestry and the world of Barberini present new research at a symposium in Eugene

- Nov. 29 — Noon, students from James Harper’s class, “Inside the Museum Exhibition,” share their work on Barberini and baroque tapestry

- Jan. 10 — 5:30 p.m., “Where Innovation and Technology Meet,” with Kenneth Kato, director of the UO’s GIS and Mapping Program, who led development of software application developed for the “Life of Christ” tapestries

- Jan. 17 — 5:30 p.m., “The Baroque Science of Color,” with Vera Keller, associate professor in the Clark Honors College; explores experimental research into color and textile techniques from the period of the Barberini tapestries

- Complete schedule — jsma.uoregon.edu/barberiniprograms

- Sponsors — National Endowment for the Arts; National Endowment for the Humanities; Alex & Amanda Haugland; Sharon Ungerleider; Excelsior Inn and Ristorante Italiano; Dentistry @ The Ten; and JSMA members