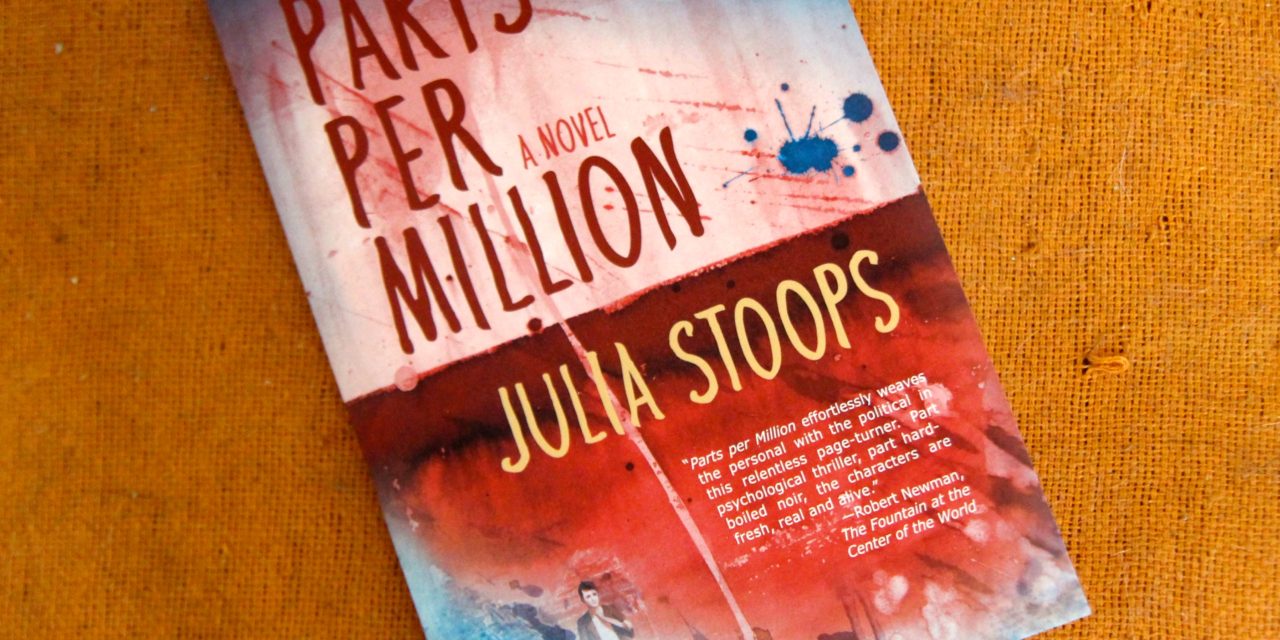

Title: Parts per Million

Author: Julia Stoops

Publisher: Forest Avenue Press, Portland, Oregon

Details: A novel, published 2018; finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize for socially engaged fiction

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-484-3777); and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

“The environment is everything that isn’t me.” — Albert Einstein

The founding of our country — its original 13 colonies — came with the raw, militant smell of activism. It’s the birth of all life, and the United States of America was no different.

America would codify and refine that activism (to the degree that it could) with the Constitution, but each year Americans mostly ignore the anniversary of the Constitution. They focus, instead, on the raw, militant smell of “the rocket’s red glare” and “the bombs bursting in air.” It’s a universal language, and the United States of America is no different.

Literary reviewer Daniel Buckwalter; photo by Randi Bjornstad

Activism, be it political or social in nature, has never left us. Its historical threads can be seen almost everywhere in our society. Yes, it often has taken the form of one-step-forward, two-steps-back. Spirit and courage have roared and been extinguished. Blood and tears have been shed. Lives have been lost. Souls have forever changed.

Much of the activism today is homogenized in the form of organized marches and speeches. Permits have to be handed out. Organization gives the appearance of a united front that’s based on the belief that the nation’s ideals today are indelibly mainstreamed in society, and there’s no need (or time or quick reward) for strident, isolating and militant acts.

Except that we are not normally united. Hard-boiled activism from fringe groups representing the social left or right still exists. The goal of these groups, always, is to throw a spotlight on a perceived problem and to move the problem to the center stage for it to be resolved.

Some would call that shaming, which seeks to divide us more. For those in power, and who control language, it might be called terrorism. Others see it as a calling. It’s dangerous work, no matter which side of the political or social divide you stand on. Property will be damaged, laws will be broken, and arrests will be made. If there are no arrests, the hard-boiled activists will live apart from middle America, off the kindness of allies and in fear of that arrest, or worse. All the while they will be planning that next big event to move the growing problem to the center stage.

All of this forms the savvy, fast-paced debut novel, Parts Per Million, by Portland-based writer Julia Stoops. It takes the tightly wound lives of three characters – Fetzer, Jen and Nelson – and throws them into the harsh environmental activism of the early 2000s.

The three have formed the Omnia Mundi Media Group. Omnia Mundi is Latin for “all the world,” and it comes complete with a web site and a monthly call-in radio show. It’s a step back from direct action, which they had known. “We’re journalists,” says Nelson. “We are trying to effect change, but we’re doing so as journalists.”

The novel introduces the trio at the intersection of despair and drive. Jen is the hard-charging true believer. “A caller on the show once said I was insular,” she says. “But how many people bother to care as much as I do about the big issues?”

Fetzer (Irving is his first name, which I love) is the lifer. He has seen everything, and he knows where all the rabbit holes are that the trio don’t want to go into. Stoops has written Parts per Million by giving each of the three characters vignettes to express themselves and move the story, and she has Fetzer and Jen speaking in first-person narrative.

But for Nelson, Stoops has him speaking in third person. He is the trio’s clipped curmudgeon, its philosopher and its conscience, almost always wearing a collar shirt and tie in the process.

Nelson also is the loner. He was an up-and-comer with the U.S. Forest Service when he was recruited by Fetzer and Jen to join the resistance. He was mainstream just six years prior, and he knows what he has lost by choosing to go underground. His wife has now divorced him, and he has gone through other women, all in the attempt to find stability after having chosen chaos.

Nelson is a believer in the cause and the inherent hypocrisy of the U.S. government, but he has his misgivings. They first surface in the novel’s opening sequence when the Omnia Mundi Media Group is filming Earth Freedom Brigade burning a barn that holds wild horses. The horses almost don’t make it out in time.

The trio is tied together at the start by Franky, an aimless trust fund kid who is a part-time model. He makes the meals and gives the three money to keep Omnia Mundi going. They are mostly broke, always live in dilapidated structures to stay under the police and government radar, and they get around in a 1985 Oldsmobile Toronado that runs on biofuel and is tricked out with custom electronics.

They start the novel chronicling Earth Freedom Brigade, and Jen recounts an interview with a tree-occupying old-growth activist who won’t talk to Nelson because Nelson is wearing a tie. Then the trio discovers a Pentagon-commissioned study with a link to a university in Portland. This leads, among other things, to stealing documents, hacking phones, a major police raid on Omnia Mundi, war protests on the streets of Portland (the second Gulf war is underway) and the sometimes vicious attempts by Portland police to quell them.

But that hard-boiled edge of the novel (which Stoops writes smartly) is for you to read. I was, perhaps, more taken with the characters. They are a motley crew, and it isn’t lost on Nelson. In his distanced, third-person narrative Nelson examines the pitiful nature of it all: “Look at them now. Three misfits and a goofy part-time model. They left behind direct action to become a media group. The free press is supposed to be a linchpin of democracy, right? But what good is it doing when so few are listening …”

Then there’s Sylvia. She’s a double agent who supplies Omnia Mundi with information on the latest proposed timber sales. And there’s Kate Simms, a reporter for the Oregon Herald who will play a vital role for Omnia Mundi professionally, and Nelson personally.

But the character I was most fond of was Deirdre. Sweet, sweet Deirdre, an Irish lass who has overstayed her U.S. visa. Franky finds her on the street — strung out on drugs and in deep need of detox — and drags her to the house.

No one quite knows what to do with Deirdre. Fetzer correctly senses the problem and gives the new guest the basement. Nelson is clueless in a clumsy way, though when Deirdre begins to clean up and shine, he sees a physically delicate, beautiful young woman he can rescue.

Jen is horrified. In part, Jen fears that Deirdre is a government plant. Mostly, Jen doesn’t want to be bothered. “I just don’t get it. Franky literally found her on the street.,” she says. “I mean, I’m all for saving the world, but not one indigent at a time.” Yes, Jen is that insular.

As she detoxes, Deirdre reveals a heart of gold. Jen eventually comes around, and Nelson is smitten to the point of proposing and marrying her (for all of one day). Deirdre drives the historical narrative by peppering everyone with questions, especially Fetzer, the lifer, and she proves to have an artistic flair with the camera, chronicling all the characters mentioned above.

She exposes, too, how each of the characters — notably Fetzer, Jen and Nelson — have lost, or never had, a thread of family. There is simply no love or sense of communal support in Omnia Mundi. Everyone, even Jen after some time, awakens to this.

When they do, though, it’s too late for Deirdre. She may be off the hard drugs, but she now is an alcoholic in search of her Irish Catholic roots. She goes to church and wears a crucifix everyday in the end, which mystifies the group. She goes through blackout binges before drowning in the Willamette River, presumably after another blackout, the day after marrying Nelson.

“She seemed happy,” Nelson says to Fetzer. “I mean about being married, starting a family.”

But Deirdre wasn’t, and no one with Omnia Mundi could – or had the capacity to – identify her demons. The group, frankly, was wrestling with its own demons.

Nelson, who at his philosophizing best can drive a stake to the heart of any quandary, nails the problem: “We’re all so lost in our own issues. But we’re so tightly woven into so many networks and systems, and so dependent on them not just for our survival, but for the continued ongoing creation, moment to moment, of our selves, that self-centeredness is just petty. Don’t you think?”

That’s a beautiful passage, and words to live by for all of us.