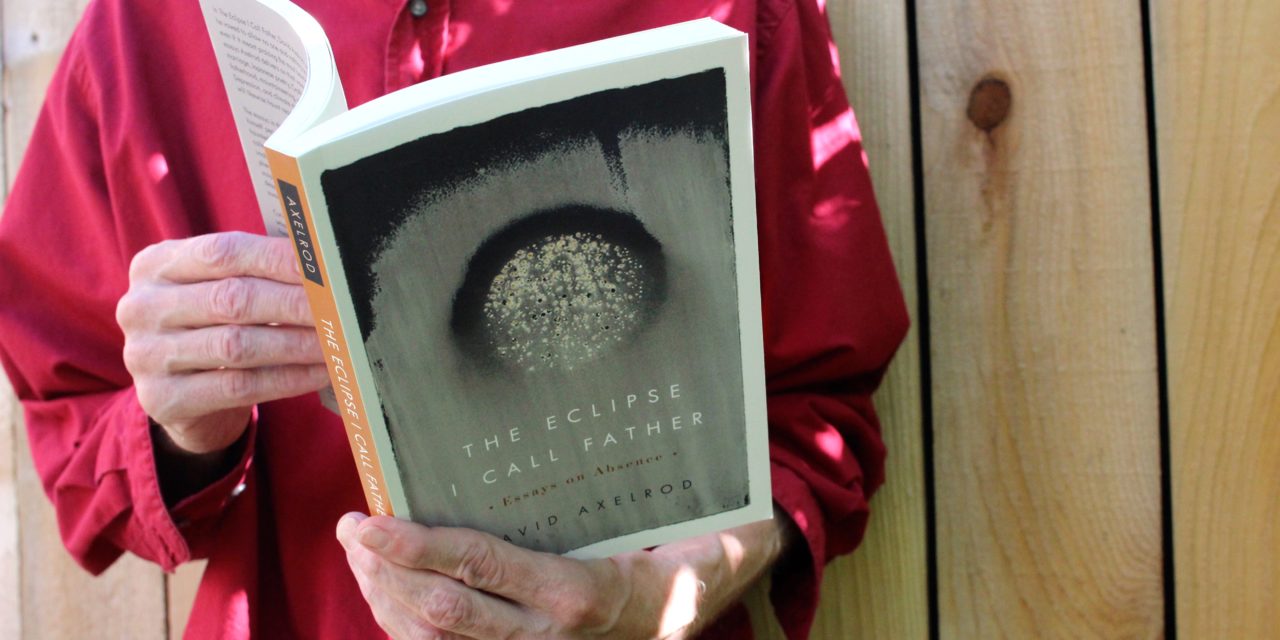

Title: The Eclipse I Call Father: Essays on Absence

Author: David Axelrod

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis; 2019

Local availability: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street, 541-484-3777; J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway, 541-342-2002.

By Daniel Buckwalter

I swear I remember the structure of the day, just none of the details.

It was overcast. It was western Oregon, so of course it was overcast. However it started, I know it was in the cafeteria during lunch. It moved to the concrete basketball court after lunch, and events unfolded from there.

This was my one and only fist fight. I was 10 years old, I think, and for the life of me I can’t remember the kid on the other side or even what the fight was about. Did I even land a punch? Did he? I have searched high and low for the memories, but nothing comes to me.

Reviewer and writer Daniel Buckwalter; photo by Randi Bjornstad

Except this: Hours after the fight, in gym class, another kid came to me and angrily declared that he was on the other side. He was against me. I stared at him in silence. “There are no sides,” I finally said. “It was stupid.”

I wish I knew what possessed me to say that. I wish, too, that I had remembered that line in my young adult years. It could have saved me much trouble.

All of this came to mind while reading the essay, Boxing Lessons, David Axelrod’s account of and lessons learned from fighting first Robbie, then Dwayne, as a youth in Alliance, Ohio. It is one of 13 essays in a collection entitled The Eclipse I Call Father: Essays on Absence by Axelrod, who lives in La Grande and is the director of Eastern Oregon University’s low-residency master’s of fine arts program in Creative Writing.

If I don’t have Axelrod’s memory, I share his sense of fairness and love, and the keen absence that is loss. It is seen from his youthful gaze at Muhammad Ali, the otherworldly hero who was rehabilitating his career, and the wonder of the tranquil beauty that is the Pacific Northwest and Montana. It is spiritual to Axelrod now. That spirituality resonated as a teenager, after watching Ali lose to Joe Frazier.

“I vowed to allow no one and nothing I loved to pass from this life without praise,” he writes, “even if I must praise the most bewildering losses.”

There was loss in Axelrod’s life. The title of the book is the centerpiece essay. It details the rocket ship, and later the eclipse, that was his father, Marvin.

Marvin was not yet 20 when his son was born. He was spontaneous, impulsive, reckless. He had airplanes, boats, flashy domestic vehicles, and race cars. There were wrecked cars and planes. They were replaced by more cars and planes.

He and his buddies loved skydiving. They had formed Skydiving Unlimited. All of this was supported by “the glory days” of the family’s junkyard business. Life was good, perhaps nursed along with a Carling Black Label and a pack of Lucky Strikes.

Being married and having a toddler son seemed incidental to Marvin. “At first my mother must have found this form of living large attractive, though soon the extravagance became maddening and she agitated for him to behave like an adult,” Axelrod writes. “Agitating, though, did little good is this regard, as my father was too preoccupied with his desires to be even remotely aware that his wife’s frustrations might require him to moderate those desires.”

The eclipse passed on Memorial Day in 1962, near Massillon, Ohio. Marvin and four other men from Skydiving Unlimited were overhead, in a newly purchased Stimson V-77 Gullwing. All looked good, eyewitnesses said. Then the engine stalled, the plane turned nose down and crashed into a hillside, bursting into flames. Marvin and one other man perished.

David Axelrod was only four years old.

I was eight when my mother passed. It’s a hollow, lonely experience. Identity is struck down before legacy can be passed down. A child seeks spiritual solace during this time. That spiritual solace is maddeningly slow, because the child can’t form thoughts and speak about the trials. There’s no language for the child to utilize.

Eventually, though, the grace of life carves other roads. Axelrod would marry, have children, travel, teach, and write. The children would leave for their adult lives, and Axelrod and his wife would be empty nesters, inviting others for dinners to fill the void.

Thus begins my favorite essay, The Old Marriage. For this dinner, there are two sisters. One asks a startling question: “Is it possible to give a proper eulogy for a couple who loved longer than you have lived?”

She is speaking of the sisters’ parents, and it’s a question I asked after my father died four years ago.

One of the sisters elaborates. “’If you think of it in those terms, we make the greatest claims on them, though we’ve been less a part of their lives than we imagine. And their siblings even more so, scattered and estranged from daily life. Their closet friends know them better than anyone else, but few of them will outlive our parents.”

That should make people stop and ponder. It did for Axelrod. “All we can ever offer each other,” he writes, “is this assurance: ‘You are not alone.’ And perhaps this, too: ‘I will not betray you.’ ”

The Eclipse I Call Father: Essays on Absence. A wonderful summer read.