By Daniel Buckwalter

War is insane, of course, but recorded history dates armed conflict to 1479 BCE when Thutmose III of Egypt battled an alliance of former Egyptian territories under the leadership of the King of Kades.

Undoubtedly, warfare happened even earlier, before civilisations developed the talent to write about it.

From civil wars to revolutionary wars, wars for economic gain or territorial gain, wars of revenge and religion, nationalistic wars, defensive or pre-emptive wars, mankind seems to have an unlimited appetite to annihilate “enemies” from within and without. Some of the categories (nationalism, perhaps) are used to fuel war for other categories (pre-emptive).

Mankind also invents more cold-blooded measures for killing. A nation’s military depends on this so-called advancement.

This year, on Sept. 2, marks the 75th anniversary of a Japanese delegation formally signing the instrument of surrender on board the USS Missouri, marking the official end of World War II.

That came only after the United States twice exploded nuclear bombs over Japan, in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The acute effects of the bombings killed upwards of 146,000 people in Hiroshima and 80,000 people in Nagasaki.

Seventy-five years, and it’s not as if mankind has seen consistent peace since World War II. We still are nowhere near to being the blended family of civilization.

Yet the sharp, saddening effects of these wars are better told by the innocent men and women, as well as the innocent boys and girls, who had no say in their nation’s affairs, and who didn’t desire anything more than to live in simple peace.

These stories were on full display Sunday afternoon at the First Church of Christ, Scientist in Eugene when the Delgani String Quartet, in three pieces that spanned three centuries, fleshed out the stories of the common person in a concert titled How We Remember.

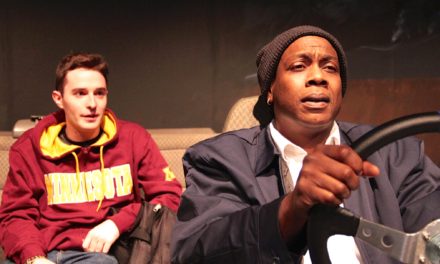

From Franz Joseph Haydn’s Emperor to the world premier of A Thousand Cranes by Boston-based composer Dr. Elena Ruehr to Steve Reich’s Different Trains, Delgani (violinists Jannie Wei and Wyatt True, violist Kimberlee Uwate and cellist Eric Alterman) told the stories of children and adults navigating the chilling darkness of wartime hell.

It was an emotional concert. In introducing the premier of A Thousand Cranes, Ruehr spoke of her father escaping Nazi Germany and the stories he told of that experience.

Before that, Uwate spoke of family members who were detained in Japanese internment camps. More than 1,000 hand-made paper cranes (folded by the close-knit Delgani family) hung nearby on stage, largely representing “a symbol of hope,” Uwate explained.

During intermission and after the performance of A Thousand Cranes, Uwate looked spent. Indeed, Delgani’s matchless precision — always a staple of the quartet — was surpassed on Sunday by the raw and tense drama of the subject and the musicians themselves.

This was a performance from the heart.

And there still was the second half of the program to be played. That was the Reich piece, which had three movements (America — Before the War; Europe — During the War; and After the War).

Different Trains on Sunday was the audio recording of interviews with Americans and Holocaust survivors against the backdrop of recorded train sounds from the time, sirens and warning bells, all accompanied in part by the San Francisco-based Kronos Quartet.

Delgani effectively added its own touch to the audio of the 1989 piece, lending harsh and stirring phrases as well as soft, affecting expression. The result was at once loudly scratchy and quietly frightening. Fear and dread in overdrive.

Delgani received a standing ovation for this concert that was months in the making, as well as it should. But it still was not done.

The show concluded with a short encore, something Delgani does not typically do but in this case was a poignant and dignified plea for peace.

It came in the form of a brief poem — A Walk to Caesarea (Eli, Eli) — written by Hanna Szene in 1942 and first set to music in 1945 by David Zehavi. It is part of the Israeli canon of songs sung on Holocaust Memorial Day (Yom HaShoah), and in this series, Delgani plays a version of it that Alterman, the cellist, arranged.

My God, My God

May these things never end:

The sand and the sea

The rustle of the water

The lightning in the sky

The prayer of man.

How We Remember, I hope, can be reshaped to How We Project, and that we carry spiritual deliverance to everyone. Let’s begin, finally, to be the blended family that we can and should be.

How We Remember with Delgani String Quartet continues at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 14, at the Christian Science Church, 1390 Pearl St. before performing the same show at 3 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 18 at the First Church of Christ, Scientist at 935 High St. SE in Salem, and 3 p.m. on Sunday, Jan. 19 at the Lincoln Recital Hall (Room 75) at Portland State University.

How We Remember

When: 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, January 14

Where: First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1390 Pearl St., Eugene

Details: “Oregon’s Delgani String Quartet presents a concert focusing on a retrospective of the events of World War II, specifically, the internment of Japanese-Americans. The concert includes a new commission by composer Elena Ruehr, a performance of Steve Reich’s Different Trains, and an initiative to fold 1000 Origami cranes for display at the performances.” Wyatt True and Jannie Wei (violins), Kimberlee Uwate (viola), Eric Alterman (cello).

Tickets: $28 individual tickets, $10 student tickets

Information: 541-579-5882, delgani.org/20192020season/