By Daniel Buckwalter

I have cats. I’ve had many throughout the years. They are my pride and joy, ranging in age from six months to at least 17 years. We are family. I talk to them. They talk back.

Don’t laugh.

I grasp Elwood P. Dowd. He’s a gentle soul, carefree and exceedingly kind. And he has a white rabbit. His name is Harvey.

This is not an ordinary white rabbit. He is more than six feet tall, and he and Dowd talk excessively about subjects great and small. They have formed a partnership and a deep friendship over the past many years. They have become men-about-town, mostly at bars with their ever-present business cards, much to the chagrin of Dowd’s sister and niece, each of whom has her own social-climbing aspirations.

Elwood P. Dowd, they believe, is crazy, and they want him gone (to Chumley’s Rest Sanitarium), so they can live in peace and continue to plot to be women-about-town.

The women believe this because Harvey is invisible to them. Harvey is invisible to everyone except Mr. Dowd.

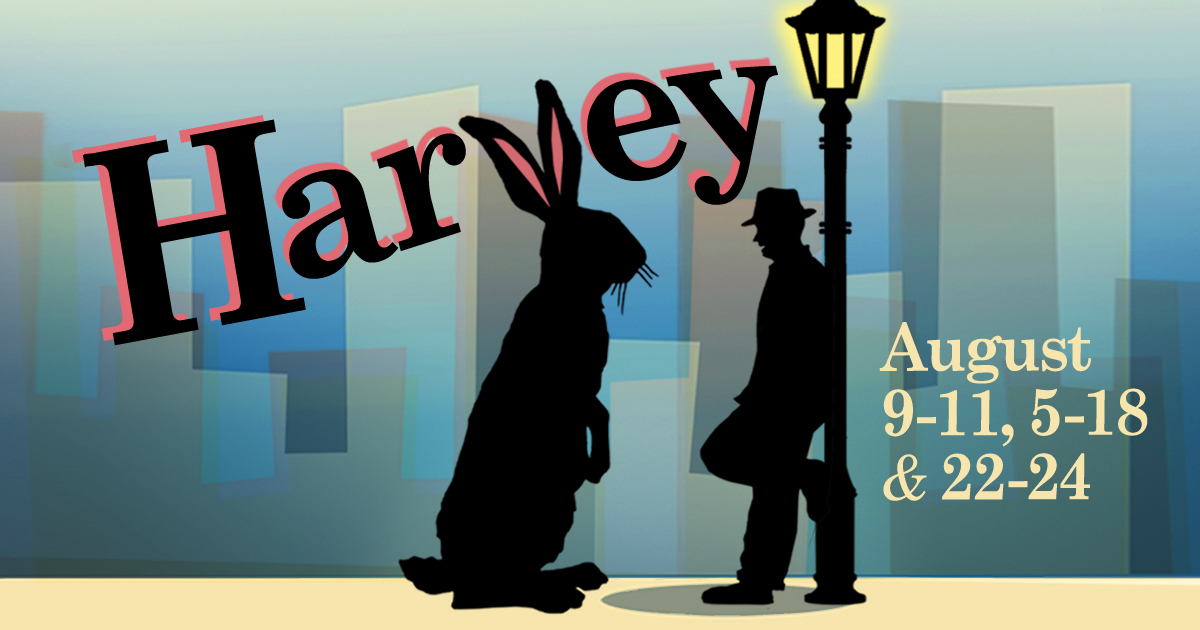

Thus begins the adaptation of Harvey, the 1940s Pulitzer Prize winning play by Mary Chase, a comedy now playing with tender care at The Very Little Theatre, under the direction of Kari Welch. It has had successful runs at many playhouses, and the great Jimmy Stewart played the role of Elwood P. Dowd on stage and film.

This production comes with a charming change of sets, back and forth from Dowd’s home to the Chumley Rest Sanitarium, by four discreet actors whom I take to be animals on the sly. Also, at the end, Elwood P. Dowd tap dances with Harvey to Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit. It’s a must-see for the two remaining weekends it plays.

The affable Dowd (Russell Dyball), his sister Veta Louise Simmons (Mary McCory) and her daughter Myrtle May Simmons (Sarah Nesslin) are a strong example of a dysfunctional family that talks over each other. It leads to misunderstandings and a near brutal decision to give the “delusional” Dowd an injection to make him a perfectly normal human being, whatever that may be.

Before that, however, Veta Louise is mistakenly committed to the sanitarium by Dr. Lyman Sanderson (Kelly Oristano). Orderly Duane Wilson (Adam Leonard) joins Dr. William Chumley (Rod Anderson in an all-out search for the “escaped” Elwood P. Dowd, who is simply enjoying life with Harvey.

All the comedic mishaps lead to the final scenes in which Veta Louise — with the help of the invisible Harvey — comes to her senses and decides to let her brother, Elwood P. Dowd, be himself.

The curtain closes with the tap dance scene between Dowd and Harvey.

Comedy though it is, Harvey hits upon the timeless problems of alcoholism and loneliness (Dowd was the sole caregiver for his deceased mother), and yes, mental illness and how it was treated in the 1940s. There is a touching turn in Act 2, Scene 3 when Dowd ruminates to Sanderson, Wilson, and Nurse Ruth Kelly (Katelyn Lewis) how Harvey came to be, and more importantly, why he thrives.

People walk into bars with problems larger than life, Dowd says. They need to unload. Harvey, the invisible rabbit, is the perfect vehicle. The people feel better. Their problems are now manageable.

They are happier.

Dowd notes that the friendships are seldom long lasting, so there is the next bar and the next bar. On one level, it’s a sad existence. Yet in the next scene comes the signature line of the play. It makes me wonder if Elwood P. Dowd was once the very social climber his sister and niece are in the play, until he had to be his elderly mother’s caregiver. It makes me wonder if he’s not wiser than all of us.

“My mother used to say to me,” Dowd recounts, ” ‘In this world, Elwood, you must be oh so smart, or oh so pleasant.’

“For years I was smart,” he said. “I recommend pleasant.”

Words to live by, maybe especially these days.