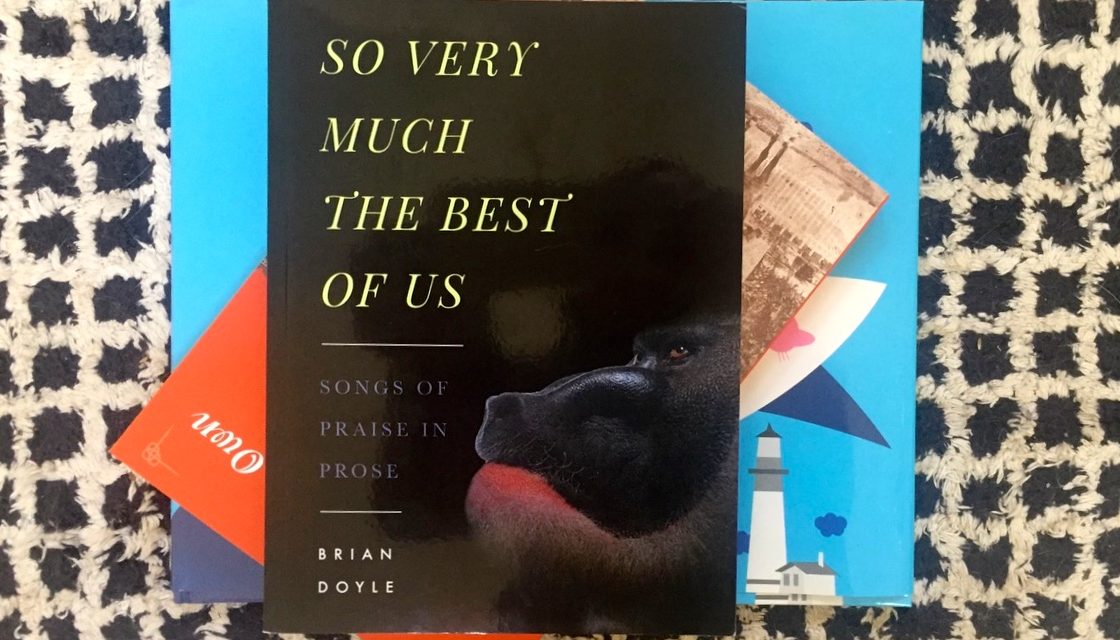

The Book

Title: So Very Much The Best Of Us: Songs of Praise in Prose

Author: Brian Doyle

Publisher: ACTA Publications, Chicago

Available: J Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway, Eugene; 541-342-2002

By Daniel Buckwalter

Another Ash Wednesday comes and goes. This year’s Ash Wednesday was on Valentine’s Day, and we were reminded again of our mortality in the grand, romantic fabric of this life. The older you are, the fewer reminders you need, perhaps, but always we are reminded. The forty-day march of Lent follows — arduous for the orthodox, softer for the rest of us. Then comes the three-day commencement of the death and resurrection.

This year Easter is on April Fool’s Day. I don’t know the significance of that, but I do believe that for Lent, a most unfoolish read is Brian Doyle’s “So Very Much The Best Of Us: Songs of Praise in Prose.”

Doyle is the editor of the University of Portland’s Portland Magazine, and as he notes in the introduction, this collection of essays is an attempt to tear down the spiritual and philosophical walls we all build and to seek our common humanity.

“I have no patience with those walls anymore,” he writes.

Doyle does this in part by burrowing into his beloved Catholic Church and the small, daily miracles of the faith. He acknowledges the troubles of the Church — it would be impossible not to. “But that’s the crust, the surface, a part of the package, not at all the whole package,” he says.

Of Catholicism, Doyle avers, “It’s not about NOT. On the much deeper level it is not about what should be prevented but about what is possible. On the deepest level it is so revolutionary that we hardly ever whisper or acknowledge or roar that truth. But it’s so.”

Mostly, though, the essays of “So Much The Very Best Of Us” are a chorus that spills sunlight on the everyday miracles of life, the tenderness and mercies that hardly draw attention normally, but bind us as families and communities.

There’s “His Dad”, the story of Doyle’s college roommate whose father died suddenly, and many miles away from the college, the night before. Young men – perhaps not even of drinking age – form a line at the dorm room door to offer a hand in condolence.

“How to Love Your Neighbor Who is a Roaring Idiot or Even Worse” is an essay written twelve years to the day after the 9/11 attacks. Doyle lost three life-long friends in that attack, all of whom he knew while growing up in New York City. It is an ode to them in part, but it also is a hard look on the power of forgiveness for the criminal, murderous among us … Osama bin Laden, in this case.

“But if you and I cannot believe that God made even them, breathed His love into their hearts as infants, gave them their chance to sing and share the Gift, then we are shameful liars,” Doyle writes. “That is what Catholicism demands. It is about love, period. It is not about easy love. That is the revolution of it, the incredible illogical unreasonable genius of it.”

Doyle expands the everyday intricacies of life to include the comfortable material extensions of ourselves. “The Cap” is a tribute to his brother, who died a year earlier, and for whom Doyle writes, “his shoes as big as boats waited for him in the slanting sunlight of the mudroom of his house where hung also his caps and hats, and do we ever think about what a worn familiar old cap might feel, having lost the head that loved it for thirty years? Do we?”

As someone who favors a baseball cap almost every day, I can say yes to that. “We are so sure that we are the only ones who feel things,” Doyle notes, “but how very wrong we might well be.”

There’s the father and college-age daughter in “Visitation Day.” There are essays about family, Ordination and other aspects of the Church. But my favorite essay is “The Room in the Firehouse.” It is the story of an AA meeting in a firehouse. Doyle accompanies an acquaintance to the meeting, and quickly Doyle is more impressed with the raw, freewheeling and emotional structure of the meeting than the acquaintance is.

“One man’s voice shook when he spoke and the man next to him reached over and put his gnarled hand on his shoulders. Even though many of the speakers were wry and funny, their stories were not. Their stories were awful.”

Later, Doyle writes of the meeting, “I wish my friend was not dismissive of those poor people. It seems to me that those poor people are the wealthiest people I ever saw in honest humility.”

Doyle stitches these narratives into the Church with two essays in particular – “His Genius” and “Haunting Friday.” In “His Genius,” Doyle writes of “contemplating an even subtler and more devious aspect of His genius: the fact that He adamantly and deftly refuses to appear in public, except by reflection and intimation …” And that is for the best, Doyle notes. “But if we saw Him we would not yearn; and this is genius. If He spoke to us clear, if He laid His starry hand upon our perspirant brows, we would be awed and thrilled, but we would not yearn; and this is genius, that He hideth from us and will not be seen, and so we yearn and doubt and must cut our own paths through the thickets.”

And there is a larger reason for this, Doyle tells us in “Haunting Friday.” He is us. “How apt and right and perfect that the Creator, poured into the skin of a young brown man during the reign of Gaius Octavius, would be neither handsome nor rich, charming or muscular, famous or wealthy; a regular joe, a man you would never pick out of a crowd, although you might well finger Him in a police lineup. Adamant inarguable astonishing genius: us!”

At their best, the world religions lift the sights and souls of their followers (all a mosh pit of sinners) to spiritual heights previously unimagined. The struggles for the faithful are daily and sometimes tedious. But the rewards, though seemingly small, are everlasting. The faithful become the peacemakers as a result. Brian Doyle’s “So Very Much The Best Of Us” is a testament to these rewards – the tenderness and mercies – that lift us all.