By Randi Bjornstad

Minority Voices Theatre, a program of The Very Little Theatre, continues its mission “to offer opportunities for members of minority or marginalized communities to participate in the collaborative art of theater as actors, writers, directors, designers and audience members” on Nov. 12-13, with staged readings of two plays.

Hattie’s Vote

The performance begins with Hattie’s Vote, written by local playwright Dorothy Velasco and directed by Hershell Norwood.

It is the story of Harriet “Hattie” Redmond, a Black woman who worked as a hairdresser in Portland — at a time when Black people officially weren’t allowed even to live in the state — and who became a major advocate for the African-American population there as well as a leader in Oregon’s women’s suffrage movement.

According to historical research about Hattie Crawford Redmond, her parents, Reuben and Lavinia “Vina” Crawford, had been born into slavery in the South, but at about age 13, Reuben was sent by his enslaver to St. Louis, Mo., to learn the intricate craft of ship caulking. He later used that knowledge to save enough money to purchase his and Vina’s freedom.

Harriet “Hattie” Redmond was an important pioneer in minority rights and women’s suffrage in Oregon.

Hattie Crawford was the oldest of the couple’s eight children, and in 1868, when she was 6 years old, the family moved to Portland, “sponsored” by a farming family in Hood River who formerly had been slaveholders but had moved to the North, where they preferred to hire laborers who had worked under enslaved conditions. Without that “sponsorship,” the family could not have relocated to Oregon, where the law, since 1857, had forbidden Black people from settling in the state, voting, owning property, or becoming employees.

Just a few months after their arrival in Oregon, their “sponsor” suddenly died, his land claim was sold, and the Crawfords, who had purchased their freedom, moved to Portland, where there was a small Black community near what is now downtown. Reuben Crawford went back to ship caulking, became an active member of the Caulkers Union and was considered one of the best ship caulkers on the West Coast. His influence encouraged Hattie to become politically and socially active.

In 1892, at age 30, Hattie Crawford married Emerson Redmond, who worked as a waiter at the Portland Hotel. The couple had no children, and the marriage was unhappy and didn’t last long. Hattie Redmond, being female, could not find work in a trade as her father had, so she worked as a domestic. But she carried on the socially active traditions she had learned from her father, especially in the area of women’s suffrage.

When Oregon voters — meaning men — finally adopted legislation in 1912 to extend voting rights to women, Redmond registered to vote at the earliest opportunity, in 1913. She served as an officer in the Colored Women’s Republican Club, taught Sunday School, was involved with the Oregon Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs, all while working as a janitor for 30 years at the Portland Federal Courthouse. She died in 1952, in her 90th year. She is buried in Section 11, Lot 51, Grave 2S, of the Lone Fir Cemetery in southeast Portland.

Nat Turner’s Last Struggle: Finding His Way Home

Second on the program, the story of Nat Turner, written by P.A. Wray and directed here by Stan Coleman, tells the story of a far more complicated — and controversial — figure in American history.

Often portrayed as a rebellious slave at best and a murderous fanatic at worst, Nat Turner’s Last Struggle focuses on the Turner’s role as a preacher who drew on scripture as a basis for racial freedom, who longed for his own self-emancipation, and who nonetheless became the catalyst for one of the most violent slave rebellions in the South.

Wray’s play focuses on the last hours of Turner’s life on the day of his execution for his role in the carnage, derived in part from Thomas Gray’s book, The Confessions of Nat Turner, combined with lore and tradition associated with the historical events. Turner was executed by hanging on Nov. 11, 1831, in Courtland, Va., then known as Jerusalem.

Nat Turner was born on Oct. 2, 1800, in Southampton County, Va., to Nancy Turner, called by the same surname as her enslaver’s family. Benjamin Turner enrolled the baby as Nat. Little is known about Nat’s father, who it is believed may have escaped from enslavement early in the child’s life. When Nat was about 10 years old, Benjamin Turner died, and his son, Samuel Turner, “inherited” Nat and other slaves as property.

As a child, Nat was intelligent and precocious, learning to read, write, and reason well beyond his years. He also became deeply religious, and often experienced “visions” that he attributed to missives from God. In fact, at age 21, he apparently escaped from enslavement, but a month later, directed by a vision, he voluntarily returned to the plantation. He often delivered sermons to other enslaved people, who gave him the nickname, The Prophet. By 1828, he reportedly had become convinced by study and his visions that he was called by Jesus Christ to fight against the social order that kept him and other Black people under the yoke of the white economic and social establishment.

Throughout 1831, Turner began to interpret various signs — first a solar eclipse, then a serious illness of his own, and finally a greenish tinge in the atmosphere possibly related to a far-distant volcanic eruption, and in fact Mt. St. Helens in Washington State is known to have erupted that year — as signals that it was time for the enslaved to begin their rebellion.

On Aug. 21, 1831, Turner and some 70 other free or enslaved Black recruits launched their attack, freeing slaves as they went from farm to farm and killing white people who resisted, numbering about 60, but sparing whites whom they believed did not consider themselves superior to Blacks.

In retaliation, the government of Virginia executed more than 50 Black people, and its militias killed more than 100 more, both enslaved and free. Reaction to the rebellion spread throughout many other communities throughout the South, with estimates of resulting deaths of Black people ranging as high as several hundred.

Turner, who never left Southampton County, was discovered and arrested on Oct. 30, 1831. He was tried on Nov, 5, 1831, convicted, and sentenced to death, He was hanged on Nov. 11, 1831. His body reportedly was brutally mutilated and possibly buried in an unmarked grave, although there have been claims through the years that his skull may have been retained. According to a story in the Virginian-Pilot newspaper in August 2021, there are at least three skulls in museums, including one in a laboratory at the Smithsonian Institution, that are being studied for possible identification as Turner’s.

Minority Voices Theatre

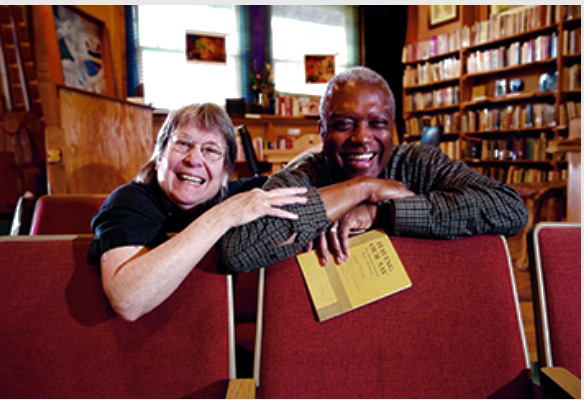

Local theater directors and producers Carol Dennis and Stan Coleman co-founded Minority Voices Theatre in January 2017 as a project of The Very Little Theatre. The group produces staged readings of plays not regularly represented on stages.

“Theatre can give people a sense of belonging, but only if they actually see themselves represented,” Dennis said of the effort. “It’s very difficult for local theater companies to produce plays that feature characters of color or focus on the stories of minority communities. The pool of experienced actors here is not very diverse.”

That’s one reason staged readings can help bring these works to light, because a staged reading is just that — actors reading from scripts with a minimum of effort and expense in terms of costuming and set design.

“Doing staged readings will create opportunities to perform plays with minimal rehearsal time and low production costs, and maybe help determine if the local community has the resources to create a full-scale production,” Coleman said.

Staged readings can entertain as well as inform audiences, and they also can provide an avenue for would-be actors to hone their skills to pursue broader acting opportunities, he said.

At The VLT: Hattie’s Vote and Nat Turner’s Last Struggle

When: 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 12; and 2 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 13, 2022

Where: 2350 Hilyard St., Eugene

Tickets: $5-$25, on a pay-what-you-can basis

Information: 541-344-7751, TheVLT.com, or minorityvoicestheatre.org

Carol Dennis and Stan Coleman founded Minority Voices Theatre in 2017