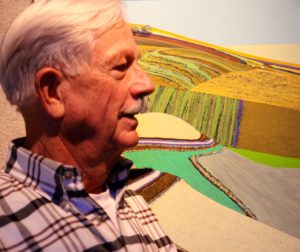

(Above: Detail from a large acrylic-on-canvas painting, “View Point #3,” by Eugene artist Jon Jay Cruson, part of a show at the White Lotus Gallery)

By Randi Bjornstad

At this point in his “art-is-my-life” career, Jon Jay Cruson is in a phase of painting vividly colored, geometric landscapes, and the fruits of that labor are on the walls of the White Lotus Gallery through Nov. 28 in a show called “Interpretation of the Landscape.”

Cruson’s career has had many previous phases, each one as meticulously pursued in technique and output as the one before and the one after.

He ticks off a list of “phases,” starting with pencil drawing that went on to lithographic prints, from there to coastal paintings. He followed that with ocean paintings in oil mixed with acrylic on redwood before turning to creating large redwood freestanding room screens, some with beautiful woodwork on one side and painting on the other.

Then it was back to a series of stream paintings in northern California — “I was fascinated by the water’s surface and also what was on the stream bed, so for a number of years I did a lot of large stream paintings, usually acrylic on canvas or masonite,” Cruson recalled — before returning to his study and interpretation of landscape.

“My career seems to go in sections of about 10 years,” he said. “I paint five days a week, usually in the afternoon and evening — the morning is mine to socialize — and I usually take a break in the winter to travel.”

He often chooses Oaxaca in Mexico for that, “because it’s a place I can afford as an artist, and the food and the people are wonderful,” Cruson said. “It’s a place that really grounds me.”

For artist Jon Jay Cruson, the process of creating gives him the most joy

His interest in vast landscapes is grounded in his earliest years growing up in northern California, in the Sacramento Valley, specifically in Yolo County in the small city of Woodland, about 15 miles northwest of the state capital.

“I left there when I was 17, when I graduated from high school and came to the University of Oregon,” Cruson said. “For some reason, there was a huge percentage of kids from my high school who wanted to go to the University of Oregon.”

That was back in the days “when you could get a degree in anything and still get a job and make a living,” he said. “But art was what I wanted to do. I got my bachelor of science in art and then did a master’s of fine arts in painting and printmaking.”

During the 1960s, he spent 19 months in the U.S. military, having been drafted three months short of his 27th birthday, when his draft status would have ended.

“When I got out, I traveled all over the United States to try to figure out what everything was about,” he said.

That was when Cruson’s “art-is-my-life” philosophy began to take hold.

He had become enamored of the printmaking process, with its combination of mechanical tasks, the challenge of mastering inks and acids and the art involved in pulling a print.

He got permission to spend a summer at Oregon State University working on his printmaking, “and at the end of the summer the head of the department had been watching my work, and he said he had a one-year position teaching drawing, design and painting and asked if I wanted to do it,” Cruson recalled.

His work that year, sharing a studio with master printmaker John Rock, led to a long-term friendship and artistic relationship.

“He did his work, and I did mine, and when it was time to make his prints I would crank the press for him and the other way around when I was doing my prints.”

There were lean years, Cruson admitted, but they were worth it. His first big break came when he met Betty and John Gray — John Gray developed Salishan Lodge on the Oregon coast among many other projects such as Sunriver near Bend and John’s Landing in Portland — and the couple had become important philanthropic figures in Oregon in the areas of arts, education and social services.

“I happened to be introduced to them because of my artwork, and Betty asked me if I was showing my work anywhere else,” Cruson said. “I said ‘no,’ and she offered that I could have one- or two-month shows at Salishan, and during that time I would also have a room and food while I painted. That basically started things for me.”

His artistic “phases” generally change “when I feel that I’m starting to repeat myself instead of finding new challenges and accomplishments,” Cruson said. “When that happens, I stop and turn to something else.”

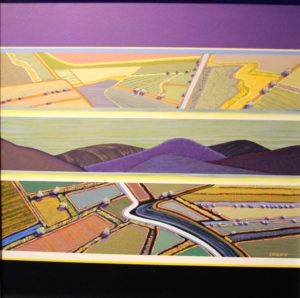

“Stacked Landscape #10” is one of dozens of Jon Jay Cruson’s paintings in his show at the White Lotus Gallery

His landscape phase has been interesting for what he has learned about the natural lay of the land.

“Being out in the field gives such a different perspective,” Cruson said. “Sometimes I’m standing at the top of a hill looking down, and other times I’m at the bottom, looking up. I try to paint what I have seen in a way that brings the two perspectives together.”

He gets his ideas sometimes by combining pieces of entirely different landscapes that he has seen, and that’s part of the reason he gives his paintings vague titles such as “Distance” or “A Quiet Road.”

“Sometimes people look at my paintings and say, ‘Oh, I know exactly where that is,’ when it’s actually a composite of several places,” he said. “But I want them to be able to imagine the places they know in my paintings, so that’s why I name them the way I do.”

Cruson has created hundreds of paintings during his career, but unlike some artists who develop emotional attachments to their work, he said he doesn’t.

“For me, painting is for the process,” Cruson said. “Certain pieces work better than others, but I think nothing of painting over an existing painting if I feel like it, and I don’t feel strongly about letting go of a piece of work.

“It’s doing it and enjoying the creativity of it that’s important to me,” he said. “To me, the final result is not what is precious.”

Interpretation of the Landscape

When: Through Nov. 28

Where: White Lotus Gallery, 767 Willamette St., Eugene

Hours: 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday

Information: 541-345-3276 or wlotus.com