The Book

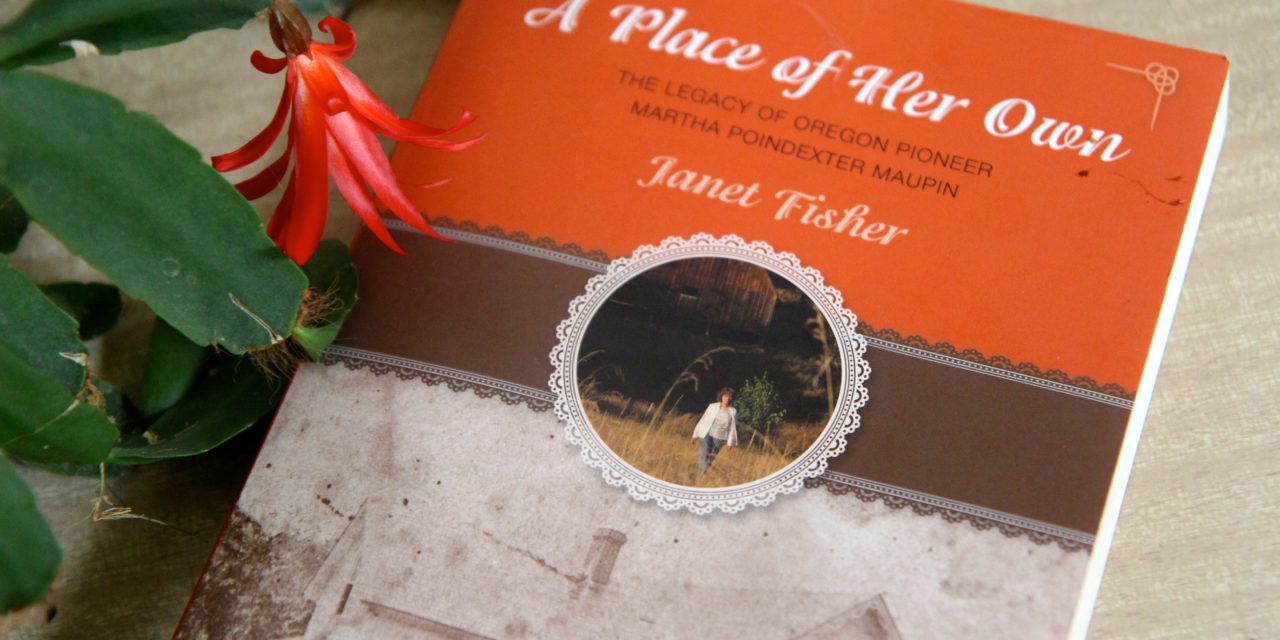

Title: A Place of Her Own: The Legacy of Oregon Pioneer Martha Poindexter Maupin

Author: Janet Fisher

Publisher: Globe Pequot Press, TwoDot Imprint

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard St., Eugene, 541-484-3777; J Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway, Eugene, 541-342-2002

By Daniel Buckwalter

The leap into the unknown – with its silent, unseen jagged edges – is an act we’ve all undertaken.

If you are young – say, 15 years old – it all may be about the adventure, with relatively few worries of the perils ahead. But what if you’ve taken many such leaps, arriving at one junction after another, each one with more at stake than the last? What if, too, you’re aware of the dimensions of the jagged edges that dot the landscape, but you have to press on – to grow and prosper – or risk killing the wanderlust spirit inside you?

The answers for Martha Poindexter Maupin form a remarkable story of courage and perseverance in “A Place of Her Own: The Legacy of Oregon Pioneer Martha Poindexter Maupin” by Janet Fisher.

Fisher, who is Martha Maupin’s great-great-granddaughter, also has written other historical novels. She grew up on the family farm along the Umpqua River in north Douglas County, the same one that Martha bought 150 years ago after Garrett, her husband, died drunk in a wagon accident in 1866.

She writes Martha’s story as fictional history and tells Martha’s story (and that of her husband Garrett) with care and meticulous detail, the latter owing to miles travelled and volumes of documents read from Illinois to Missouri to Oregon, all of which the author chronicles in her writing journey during the four interludes in the book.

At the start, Martha is a spunky 15-year-old kid who feels constrained in the family home and yearns for freedom. By book’s end, she is a concentrated, learned woman who has seen the world’s nurture and its base nature, and she understands how to navigate each. The farm, and its house, is a testament to Martha’s wandering spirit and the lessons learned, yes, but it also is an anchor she now craves after Garrett dies.

“I had to do something. I never wanted my family to live off the charity of friends and relatives. But I think the most terrible thing for me was knowing I had to decide … I had to come to it myself, say, ‘Here I will stay. Here I will take my stand’ … It was the most lonely choice I ever made.”

It was a daring decision on many levels. On a practical note Martha had to secure a loan, but as a widow — and a woman — she needed her oldest son, Cap, to arrange it. She signed for it ($1,000) but only because Cap was too young to sign the documents. Women’s rights did not exist. They couldn’t even vote. Women (and children) were the property of men, a fact that had hit home for Martha years earlier. There also was the sheer volume of work to clean up the land and build the dream frame house with a balcony.

But the decision was spiritual as well. Martha left her childhood home in Illinois with two older brothers at age 15 and married the adult Garrett in Missouri at age 16 (against the wishes of her parents and one of her older brothers). She gave birth to nine children (one while on the Oregon Trail, with Garrett lovingly – and comically – serving as the midwife), and upon reaching Oregon first settled in Lane County.

It was in Lane County where Martha firmly saw the flip side of Garrett’s impulsive radiance, that which had charmed her as a teenager in Missouri. They were married for twenty-one years, but Martha lost her husband years before he died; she just didn’t know it. Alcoholism meant that Garrett died the death of a thousand paper cuts.

Garrett’s stage was small but certain. The nuance of learning was not for him. He couldn’t read and didn’t want to. Martha would read for him. Garrett claimed he could read a man’s eyes, an animal’s movements and the growing cloud cover. All of it had taken him through manly pursuits, pitched individual battles, state-sanctioned war and then the Oregon Trail. That was enough. He wouldn’t change.

But the political and social landscape demanded he did. He fought the certainty of change every step of the way. Garrett did this by absorbing years of anger at a changing world that he, a southerner to the bone from pre-Civil War Missouri, wished to stop but couldn’t. He took it out on Martha when he believed her to be “sassing.” Garrett hit her, more than once, and hard.

Martha had enough one night and set about to get a divorce. Divorce laws were loosening, but the concept of women and children as property still lingered. There was a real possibility that Martha would not have any custody of the children, and that horrified her.

Garrett begged for forgiveness. He got it, but it was an uneasy alliance. She couldn’t stand the thought of losing her children, and now she knew her husband to the core. Garrett’s drunk escapades included a fight with a man in Eugene, and he was charged with what today would likely be assault and battery. He and the family packed for Douglas County, one step ahead of the law that in those days would not cross county lines.

So the family ended its travels in north Douglas County, but the primal screams of Garrett’s alcoholism continued. Those screams crested one day near Oakland where Garrett and Cap (barely a teenager at this point) are getting supplies. Garrett bought a bottle of whiskey, and he drank from it while walking alongside the wagon full of supplies. Cap had the reins of the horses.

Somehow the wagon tips over, and Garrett is either crushed or smothered to death. Cap gets the horses home, crying and attempting to explain the accident to Martha. Mr. Wells, a family friend, volunteers to try to piece together the story. Mr. Wells finds a reporter in Oakland who has sent the story to a Eugene newspaper because Eugene authorities had not forgotten that Garrett had skipped across the county line.

Mr. Wells also attempts to console Martha. “I did like Garrett,” he said. “When he wasn’t on the whiskey he was smart, had a fine sense of humor, loved his family— loved you.” She looked into her lap. “He loved the whiskey more.” Not so, said Mr. Wells. He leaned forward, as if to emphasize what he was about to say. “Garrett was a man who liked to be a master of things, and a man like that can’t love anything that makes a slave of him.”

That’s the spiritual definition of an alcoholic, a person locked into victory at all costs. Also, I suspect, it made Martha’s next leaps of faith – buying the present-day farmland and where she would “take my stand” – all the more invigorating. She was ready.

Martha lived to 80 or 81 (records differ), and sold the farm to her son, Cap. Today the Martha A. Maupin Century Farm, one of the few Century Farms in Oregon to be named for a woman, is still in the family, owned and operated by Janet Fisher.

Fisher’s “A Place of Her Own” is a fitting tribute to the matriarch of the Farm.