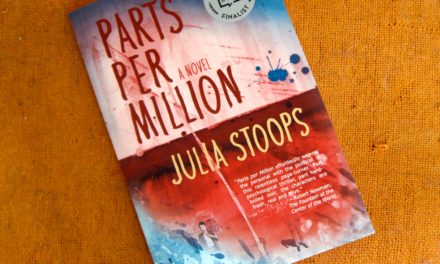

Above: Eugene author Cai Emmons has just released her latest book featuring Bronwyn Artair, a young woman whose superpower is controlling the weather. It’s titled Sinking Islands and follows the prequel, Weather Woman.

Note: The release date for Sinking Islands is Sept. 14, 2021. On that day, there will be a book launch party via Zoom, hosted by the The Tattered Cover Bookstore in Denver, Colo., at 4 p.m. Pacific time. You can REGISTER FOR THE EVENT HERE. And if you buy a book from them it will be sent to you with no shipping charges. Six other writers will read short sections of Emmons’ new novel.

By Randi Bjornstad

Two years ago, Eugene Scene published a story about Weather Woman, Eugene author Cai Emmons’ first book to feature a young woman named Bronwyn Artair, who discovers that by using her super-power of concentration, she actually can change the weather.

That 2019 article began this way:

Think of all the terrible weather events that have been going on lately — massive floods in the Midwest that wash out farmers’ crops and inundate houses and towns with mud-laden water, mile-wide tornadoes in the Southeast that obliterate everything in their paths, wildfires that destroy whole communities and take away lives that can’t outrun them — and then wonder what it would be like if you or some other superhero in our midst had the power to stop all that weather in its tracks before it caused all that deviltry.

Here we are now, and these kinds of catastrophes not only have continued, they’ve gotten even worse. And Emmons has continued to mull over these ravages of climate-change in the form of a sequel that sees Bronwyn Artair recruiting others — all different ages, genders, races, geographical locations — whom she believes she can train to do the same things and help save the world from eventual extinction.

Cai Emmons and longtime partner and now husband, playwright Paul Calndrino

But these two years also have seen devastating effects in Emmons’ own life. After experiencing difficulties with her voice and swallowing, she spent more than a year seeing a variety of medical specialists ranging from dentists to ear-nose-throat physicians to otolaryngologists to neurologists, before she finally received a diagnosis of bulbar-onset ALS, a more aggressive form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also called Lou Gehrig’s disease) that affects about 5,000 people in the United States annually.

Difficulty speaking and swallowing are classic symptoms of the disease. In Emmons’ case, eating and speaking have become difficult to the point of needing a device to assist her to communicate without physically speaking.

So, because she has been interviewed before for eugenescene.org, this time she readily agreed to answer questions in writing about her new book. For background about her first book and her writing career, the original article published by Eugene Scene is appended after the following Q&A:

Question: I would like to explore the “superhuman” concept of a person or group of people actually developing/discovering these powers that can independent of everything else affect something as dire as climate change. How did you come to cast this issue in that context? Perhaps Bronwyn and her new helpers are stand-ins for the billions of people in the world who are needed to participate together to make this overall climatic calamity not happen?

Answer: In the prequel to Sinking Islands, (titled) Weather Woman, I was interested in exploring this idea of a human being being powerful enough to control the weather. I have always been fascinated with the weather, and when I was a child I used to fantasize about how terrific it would be to be able to stop rain, to bring on snow, to create wind—or whatever. I often stared up at the clouds and imagined I was moving them with the force of my will. So at some point, as an adult, I began to formulate a character who could do just this. She is a person who is deeply connected to the Earth. She has dropped out of a Ph.D. program in atmospheric sciences at MIT and she has become a TV meteorologist. She is far too educated for her job and doesn’t much enjoy what she is doing, and after she turns 30, and her boyfriend dumps her, and she is at rock bottom, she discovers that she has this talent. Of course, if you can control the weather, you are quickly expected to do something about climate change, too. Throughout Weather Woman, this talent is only explored in terms of her individual capability. She is able to stop storms and tornadoes and fires, and bring snow, among other things, and at the end she finds herself in Siberia trying to refreeze the permafrost in order to prevent the release of methane. What she realizes at this point is that it is foolhardy of her to believe that she alone can address all the climate crises we have across the planet. So she has gone into semi-hiding, wondering what to do next.

At the beginning of Sinking Islands, she feels summoned back into action. She devises the idea that, in order to address the problem on a wider level she needs to teach others. So, she gathers people from some of the most climate-degraded places on the planet and she decides she will try to teach them. The characters she gathers are: Analu and Penina and Vailea from an unnamed “sinking island” in the South Pacific. Their island is getting flooded on a regular basis and two of Anulu’s children have died of dysentery. Then there is Felipe from Sao Paulo which is facing a huge water distribution problem even though it possesses 12 percent of the fresh water in the world. Edel is from Greenland where ice is melting at a super-rapid rate, raising sea water levels much too fast. Then there is Patty from the plains of Kansas who has lost her husband and minister to tornadoes and is intent on learning to stop them.

I wanted to show the people in this book collaborating in the interests of addressing the myriad climate problems we have, which will never be solved by one heroic individual! I was moving away from the idea of a singular superhero—or heroine.

Question: Penina is an interesting character. Is she, as a teenager, taking the role of the burden/opportunity for the next generation, and/or is she being set up in Sinking Islands as the protagonist for a future book? Do you have another book in mind? If so, what can you say about it?

Sinking Islands, a new novel by Eugene author Cai Emmons

Answer: Penina definitely represents, in my mind, the approach that the younger generations will bring to the problem. They are already having to “think outside the box” and become creative using solutions that have not yet been tried. I think of Penina as fearless and impulsive, capable of doing big things if she doesn’t become too foolhardy. Edel, her Greenlandic peer, is also very committed to becoming an activist, but she has a different path because she is a musician. Her power definitely comes through her music, and she is aware of that as her strength.

If there were another book in this series, Penina would definitely figure in it prominently, as would Edel. So far, I have no specific plans for that book (though some very rough ideas have come to mind). But I have just sold two new quite-different books, both coming out in 2022, and I think they will be keeping me busy for a while, along with Sinking Islands, coming out of Sept. 14. So the final book of this trilogy may have to wait!

Question: How does all this fit in with the challenges you are facing in your own life right now? If I am correct, you did not really know about this diagnosis when you were writing Sinking Islands, much less Weather Woman, or at least not in the early stages. How did you see yourself back then as creator and participant in the plot of these books, compared with the way you might see yourself now? It seems that you are as much a “superpower” in your personal life now as your characters are in what they are undertaking. Has the way you approach your own health issues taken any cues from the way you have developed your characters? Or the other way around?

Answer: This is a very interesting question. I always think there is an interplay between the way people write their books and they way they live their lives. You are correct that I had no idea about my ALS diagnosis when I was writing either Weather Woman or Sinking Islands. The earliest inkling that there was a problem arose back in December of 2019, when I was doing a reading in Sausalito and I realized there was something ever-so-slightly off about my speaking voice. This problem developed very gradually over the course of a year until I was given my diagnosis in February of 2021. During that time, I was speculating a great deal about what my body was telling me. All sorts of diagnoses were being bandied about. One of the interesting things about ALS is that every case is different, and I quickly realized it would not be appropriate to grasp on to anyone’s else’s experience as likely to be like my own. And this, oddly enough, is exactly what these characters in Sinking Islands experience. All the needs of their native homes are different and they need to listen closely and figure out what the Earth wants from them. They must attend closely, and then they must often act by improvising. This is very much my situation now. I must not anticipate what is going to go wrong, but simply pay close attention to my body, and when things go wrong I must be able improvise around the next deficit that arises. We are all of us, my characters and I, required to live in a state of negative capability.

Original story, posted on June 19, 2019

By Randi Bjornstad

Think of all the terrible weather events that have been going on lately — massive floods in the Midwest that wash out farmers’ crops and inundate houses and towns with mud-laden water, mile-wide tornadoes in the Southeast that obliterate everything in their paths, wildfires that destroy whole communities and take away lives that can’t outrun them — and then wonder what it would be like if you or some other superhero in our midst had the power to stop all that weather in its tracks before it caused all that deviltry.

That’s the basic premise of Eugene author Cai Emmons’ latest book, Weather Woman, about a young woman named Bronwyn Artair, who works as a TV weather reporter and gradually comes to realize that she has exactly that power.

First, almost just by thinking it, she rescues the wedding of a young colleague from being ruined by rain. Later, she finds she can stop a meteorological phalanx of tornadoes from hitting ground and destroying a community.

That, of course, sets up a lot of questions. Not only is it a heavy responsibility, but where do the ethics of it fit in? What is the justification for one person to exercise that kind of power? And where does the responsibility to interfere begin and end?

“When I set out to write Weather Woman, I didn’t start out with the idea of writing about climate change, just about this power to affect weather and the empowerment of this woman to do it,” Emmons said. “By the time I finished the book, I knew that it had more to do with examining the responsibility that she has to act when the whole world is experiencing such trouble.”

Her book doesn’t proclaim on the looming calamity of climate change and exhort people everywhere to do everything they can to forestall it, but the concept, however subliminal, nonetheless hovers in the background.

“A good novel poses questions, but it doesn’t preach,” Emmons said. “I like to write something that people can read and think about — and even argue about — afterward.”

Writing Weather Woman meant studying up on several branches of science, including physics, neurobiology, and meteorology, all subjects that Emmons wasn’t necessarily well-versed in before, either by way of academics or vast personal experience.

Always a writer

Cai Emmons grew up in the Boston area, then lived in Connecticut, where she graduated from Yale University, followed by New York, where she did a master’s degree in film writing and editing at New York University. She married and moved with her then-husband, also a film writer, to southern California, where his mother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and needed care. Eventually, the couple divorced.

By then Emmons had begun to write fiction. She enrolled at the University of Oregon, where she completed a master’s of fine arts in writing and became an adjunct instructor in the program, a position she recently resigned after nearly 20 years.

Her first novel was His Mother’s Son, which won an Oregon Book Award, followed by The Stylist, which featured a transgender main character, and now Weather Woman. She also has written a collection of short stories, Vanishing, which won a writing competition and will be published in March 2020.

Now Emmons is working on a sequel to Weather Woman called Sinking Islands, and has yet another book, Hair on Fire, in progress.

“When I finished Weather Woman, I had the feeling that I wasn’t done yet,” she said. “There were characters in the book who seemed to have more to say, and there were things in the plot that still seemed to have need for more examination.”

She doesn’t remember feeling born to write, although when she was about 8 years old, she remembers making a poetry book for her parents.

“And at age 9, I had a wonderful teacher who had us do daily compositions,” Emmons said. “His name was Mr. Stefan Vogel.”

Decades later, while attending an Oregon Book Award event, she met another author, Helen Vogel Frederick, who had a young adult book in the competition.

“I asked her about her name, and it turned out that she was my teacher Mr. Vogel’s daughter,” Emmons said. “That was such a wonderful coincidence — I think we exchanged a few email messages after that.”

In fact, she’s thinking now about dedicating Hair on Fire to Mr. Vogel and at least two playwrights who helped guide her to a career as a writer, “because I think people don’t express often enough how grateful they are to others who have influenced them in such a positive way.”

Unusual writing habit

Author Cai Emmons still prefers to write her drafts on lined notebook paper with a ballpoint pen, sitting on her bed instead of at a computer desk.

When it comes to the mechanics of writing, Emmons is a throwback to an era preceding the computer age.

Asked where she does her writing, she leads the way to her bedroom, its walls lined with bookcases and pretty much every surface covered with written materials. She plumps up the bed pillows, curls up on a bedspread covered with a riot of richly colored flowers and whimsical goat-like creatures.

Then Emmons picks up a sheaf of lined notebook paper and a ballpoint pen and begins to write.

“I always write longhand,” she said. “My brain works differently that way than if I just type it. But I realize that there are some inefficiencies in the way I do things.”

When she does transfer her written words to the computer page, “I try to type it in at first without changing things too much, but then I go back and change all the things that I noticed as I was typing. I try to do that process a chapter or two at a time.”

Her life partner, Paul Calandrino, also is a writer, of technical materials and plays.

Both being writers “works well for us,” Emmons said. “We read each other’s work, but what we do is different enough that there is no competition aspect. He’s always my first reader, and we always brainstorm ideas for each other’s projects.

“On weekend mornings, we wake up and talk about writing — and politics, of course,” she laughed. “It’s great.”

Author Cai Emmons still prefers to write her drafts on lined notebook paper with a ballpoint pen, sitting on her bed instead of at a computer desk; photo by Randi Bjornstad