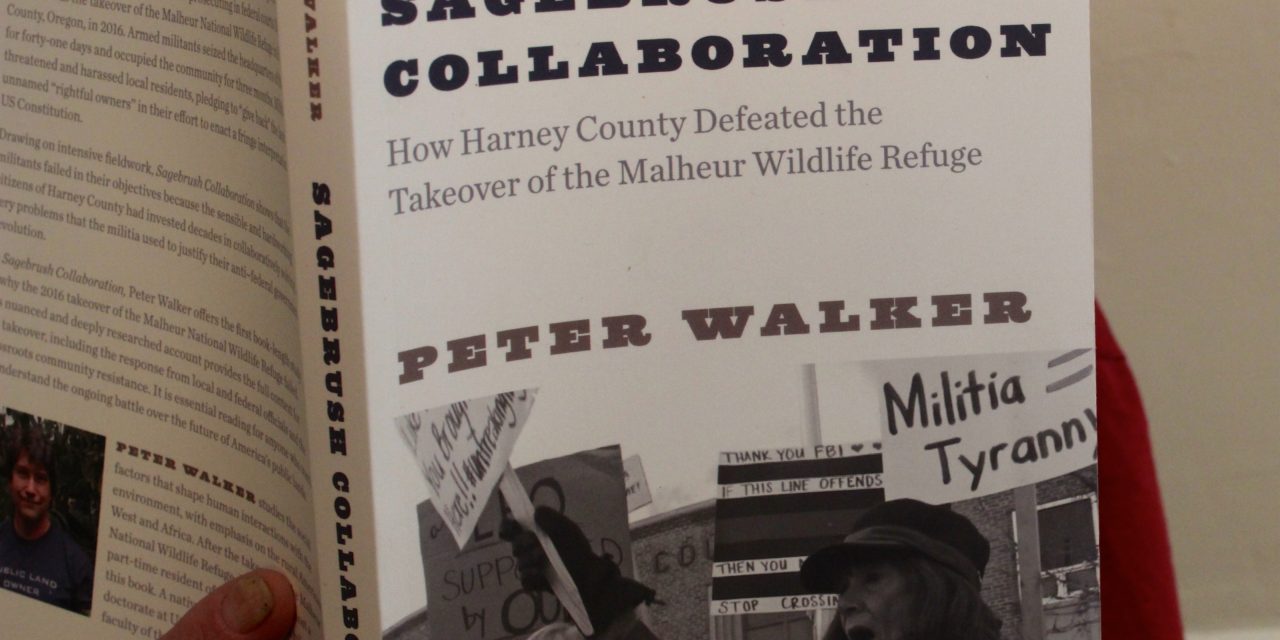

Title: Sagebrush Collaboration — How Harney County Defeated the Takeover of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge

Author: Peter Walker

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis; 2018

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-484-3777) and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

Have you, like me, ever wondered how the often crude, rude and sophomorically run 2016 presidential campaign of Donald Trump actually succeeded in getting the Electoral College votes?

OK, admittedly that’s for a different book review, but a ground-level test run for the 2016 presidential campaign, I argue, can be made in the January 2, 2016, takeover of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in Oregon’s Harney County by a group of ill-informed — some even would say blowhard — “patriots.” It was done in the name of the father/son team of Dwight and Steven Hammond, but with a rueful shout out to the Bundy family of father Cliven and son Ammon.

The 41-day takeover, and the events preceding it, had face-to-face intimidation. It had phone, email and social media blitzes designed to stir up the masses with misinformation and vague threats. It had men (almost all from out of the state) openly displaying firearms and intimating that they would carry out those threats. It had confederate flags flying from the beds of out-of-state pickups and a Safeway parking lot in the town of Burns that became the hot-spot meeting place for the transient militiamen in the dead of winter.

All of this, author Peter Walker writes, was done in a region of Oregon that with “10,226 square miles … is roughly the same total area of the state of Massachusetts, with one one-thousandth the population – 7,292 in 2016. With a county-wide average of only 0.71 percent per square mile … From the county border to the first towns, it is common to see no human beings.”

And all of it is wonderfully chronicled in Walker’s book, Sagebrush Collaboration — How Harney County Defeated the Takeover of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge. Walker, a professor in the geography department at the University of Oregon, has studied human interactions with the environment in the American West and Africa.

Sagebrush Collaboration is the first book-length examination of the takeover at the Malheur Refuge. It is detail-rich with history and of the events during the takeover.

The takeover played out in both national and international media. It divided the locals then (and still). It brought into focus — in sagebrush-dominated Harney County, no less — divisions in America that have historically existed between those who believe in strong central government and those who vehemently distrust it.

This includes, Walker noes, debates between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson at the country’s founding. It includes, too, the Civil War and its aftermath and the incidents in Waco, Texas, and Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in the 1990s. It also has historical fragments of religion, especially the Mormon faith.

Mostly, it includes the more recent argument of use of federal lands. Cliven Bundy led hundreds of armed protesters in the 2014 Bunkerville, Nevada, confrontation with law enforcement over grazing contracts and accompanying fees. This staredown on federal Bureau of Land Management acreage was the sharpest volley prior to the Malheur Wildlife Refuge.

I also set the stage for what happened in Burns and at the refuge. The damage, particularly near the sacred land of the Native American Burns Paiute Tribe, the general tension in Burns and at the refuge, the arrest and surrender of militiamen and the killing of one of its members (LaVoy Finicum) is all a matter of media record.

What’s less well known is the question of whether it was worth it. No, Walker argues, because while the Harney County residents were not unsympathetic to Ammon Bundy’s arguments for decentralizing government power (far from it), the tactics employed by the militiamen were a turnoff.

This is where the collaboration aspect of Walker’s study comes into play. Unsteady as it sometimes has been, trust has been building among disparate groups like environmentalists and ranchers in central and eastern Oregon. The creation of the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area in 2000, and the negotiations for it, is a notable example.

And since the occupation, Walker notes, momentum for collaboration has grown, especially in Harney County with the formation of the High Desert Partnership and the Harney County Watershed Council. This — and the fact that Ammon Bundy (as well as Finicum and Ryan Payne, among others) failed to properly grasp Harney County’s economic history or future without the federal government — spelled doom from the outset.

“Many ranchers in the county had observed substantial improvements over recent decades in relations between ranchers and federal land managers,” Walker writes. “Bundy appeared unable to conceive that rural, resource-dependent, staunchly conservative Harney County might not overwhelmingly share his view of the federal government as an irredeemable ‘tyranny’ that must be overthrown by force.”

Harney County residents were the winners of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge occupation. They took their county back with their voices. And they nominated some individual winners in elections in late 2016. Local officials who were “anti-Bundy” (like David Ward, sheriff), won either recall efforts or landslide elections.

And, writes Walker, “Many noted that a silver lining of the occupation was that it brought the tribe” – the Burns Paiute Tribe – “and the non-Native community, whose relationship had at times been difficult owing to a painful past and lingering racism, closer together than ever before.”

To be sure, Harney County (with its “Welcome to Harney County We Honor Veterans” entry sign) will continue to carry proudly its conservative flag.

“In November 2016,” Walker writes, “Donald Trump was elected president. Harney County cast 4,082 ballots from 4,749 eligible voters; 75.4 percent voted for the Republican candidate; 17.7 percent voted for Democrat Hillary Clinton; and 6.9 percent for other parties.”

And yet, the Malheur Wildlife Refuge was retaken and saved. Bless Harney County.