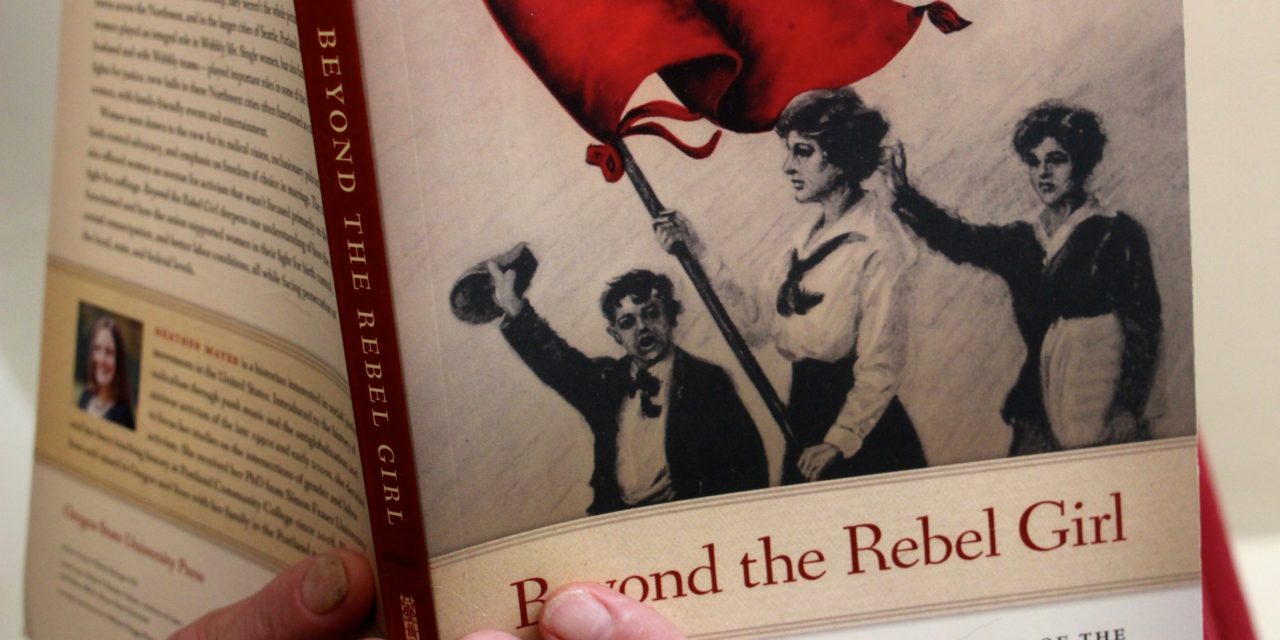

Title: Beyond the Rebel Girl: Women and the Industrial Workers of the World in the Pacific Northwest | 1905-1924

Author: Heather Mayer

Publisher: Oregon State University Press, Corvallis; 2018

Available locally: Black Sun Books, 2467 Hilyard Street (541-484-3777); and J. Michaels Books, 160 E. Broadway (541-342-2002)

By Daniel Buckwalter

It still sheds light, as most labor unions do, but the comet that was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) reached its zenith early in the 20th century.

It made its historical mark.

The IWW has been studied at length for its labor activism, yes, but also for its community-based activism and its socialist and anarchists tilts. Its members stood tall in the face of vigilantes, law enforcement and government officials.

Yet the history of the IWW and its members — known more affectionally as the “Wobblies” — has been written largely in one-dimensional terms, and from the perspective of men. With rare exceptions, women like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (often referred to as “the Rebel Girl” have been absent in the IWW’s history, seen perhaps in photos but not heard

Heather Mayer aims to change that in her book, Beyond the Rebel Girl: Women and the Industrial Workers of the World in the Pacific Northwest | 1905-1924.

Mayer, a native Oregonian who teaches history at Portland Community College, reveals the key roles women played in the free speech fight in Spokane (1909), the Seattle tailor’s strike (1912), the Oregon Packing Company strike (1913), and the case of Lilian Larkin, among others instances.

It is amazing and distressing that more than a century later, not a great deal has changed for most women in the public sphere. Yes, some women have forged paths to power and status in the vertical, hierarchical model established centuries ago — and which, interestingly, the Wobblies vigorously opposed — but at what cost to the private self?

“Respectability” is a word tossed around often in Mayer’s study of the IWW. It is used as a weapon, first against the “hobo agitator,” and it was employed, Mayer writes, by “newspapers, state and local governments, and law enforcement to emphasize union members’ outsider status and disregard for the law.” Some were beaten, and some died.

The vocal (and mostly young) women of the IWW fared no better than their “hobo” men colleagues in the battle of public opinion. Perhaps they were scarred worse, given the societal division between men and women at the time. Some were married and accompanied their Wobbly husbands. Others, like Flynn, who played a role in the IWW in the Pacific Northwest, left children behind to fight for better working and living conditions

They endured ill-defined morality laws such as the Mann Act, public ridicule, jail, sexual misconduct in jail and other indignities from the press, the police in interrogation rooms and judges in courtrooms

Yet — and further proof that the climate for women who step onto public platforms hasn’t changed dramatically in more than 100 years — they persisted

The women came in waves and with diverse talents to the IWW in the Pacific Northwest during the early years of the 20th century. There was Edith Frenette, Anna Arquett, 10-year-old Katie Phar (“the songbird of the IWW”), Agnes Thecla Fair, Florence Thompson, Becky Beck, Jane Addams, Lorna Mahler, sisters Margaret and Janet Roy, Louise Olivereau and many more in the background.

And they were radical both for their own time and for today

The women fought for reasons beyond the traditional framework of wages and working conditions. As Mayer writes in the introduction, “… the IWW engaged in women’s issues, such as birth control, agitation, and (they) advanced an economic argument regarding prostitution, seeing ‘fallen’ women as part of the working class and victims of the capitalist system, rather than morally deficient.

Mayer continues: “We see that its reach surpassed the lumber camps and hobo jungles and that it was a valid avenue in which radical working-class women could organize, educate, and agitate for social justice.

Founded in 1905 in Chicago as the Industrial Congress, the “Wobblies” did achieve many of their short-term goals, in the West generally and the Pacific Northwest, in particular

Union membership numbers, though, are unclear. It’s estimated that the peak number of IWW membership was 150,000 in 1917, with active wings in the United States, Canada and Australia. One study of the IWW during the era Mayer examines also estimates that turnover was as high as 133 percent per decade, owing to workers joining the union for a short, emergency-related period of time

Further, Mayer writes that membership in the IWW consisted of mostly itinerant Caucasian workers who began the IWW, and who formed, by far, the largest demographic in the Northwest during the era that she examines. They were tough — men and women alike — and they believed in the idea of the Pacific Northwest

“The industrialization that happened in the East over the long course of the nineteenth century happened in a few short decades in Oregon and Washington,” Mayer writes. “The volatility of that transformation, as well as the independent nature of those who moved here from other areas of the Northwest, made it a fertile ground for radicalism.

Heather Mayer’s study of the IWW women early in the 20th century is well worth reading. Beyond the Rebel Girl is a salute to these women, not to mention that the battle is not over — it is a reminder that even today, the fight must continue.

About The Author

Daniel Buckwalter

Daniel Buckwalter lives in Eugene with his five cats, affectionately known as The Russian Mafia. He has worked for three newspapers spanning more than three decades, most recently at The Register-Guard. He also has had pieces of short fiction published in literary journals through out the country.