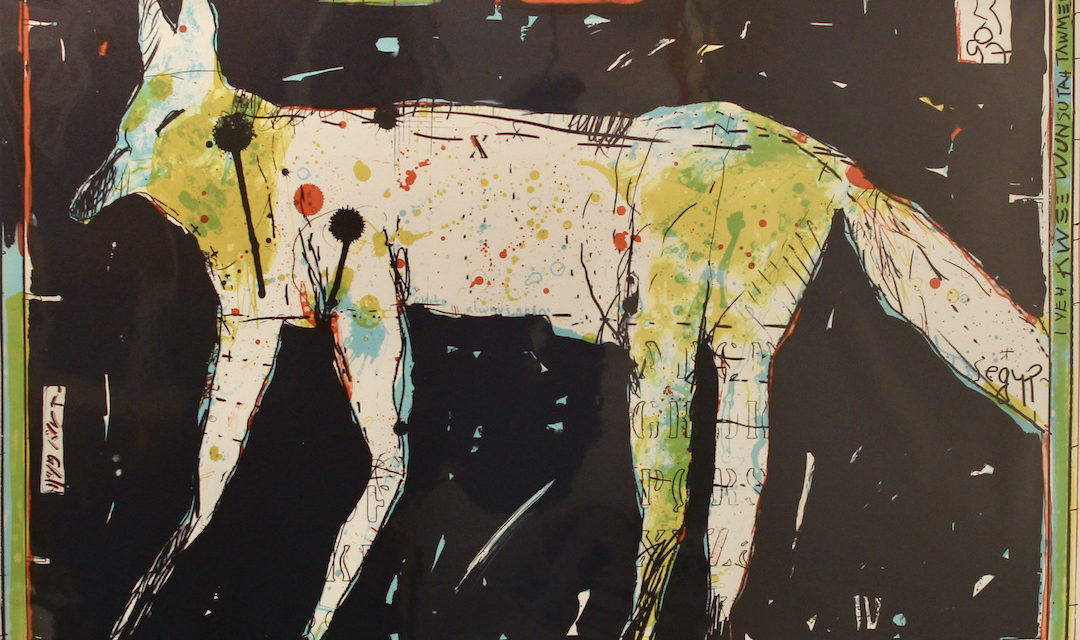

(Above: Artist Rick Bartow (1947-2016) often portrayed animals such as coyotes that reflected his Native American cultural heritage.)

By Randi Bjornstad

Gallerist Karin Clarke calls the new show at her Karin Clarke Gallery “just a tiny portion” of what the late Rick Bartow created during his several decades as one of Oregon’s pre-eminent artists.

“He was a painter, a sculptor, and a printmaker, and it is his printmaking that we are focusing on in this show,” Clarke said. “There are master printmakers who work with high-level artists and assist them with their printmaking, and that is the kind of work that is represented in this show.”

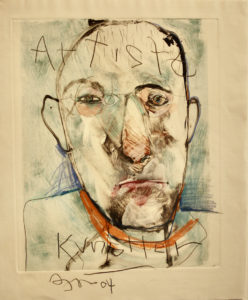

Sad Man, a monoprint done in 2004 by Oregon artist Rick Bartow

Bartow, who lived in the Newport area most of his life, was a complicated person whose many artistic facets appear in different ways in his life. In addition to a wide range of visual arts — drawings, paintings, sculptures, ceramics — Bartow also was a singer, songwriter, and guitarist.

“He was a very forceful and authentic artist, and his work reflects so many different things that happened in his life,” Clarke said. “He was Native American, and his tribe was victim to a historical massacre in the 1800s, and that was something that he felt very personally, a huge pain in his life.”

According to historical newspaper accounts, that massacre happened in February 1860 in Humboldt County, California, near the city of Eureka. Hostility had festered for years between white settlers and the Wiyot tribe after the settlers, many of whom came west with the Gold Rush, intruded onto traditionally Wiyot land, by turning their cattle loose to graze and otherwise interfering with tribal activities.

The conflict erupted with deadly force one night when a group of settlers attacked Wiyots with guns, hatchets, clubs, and knives, according to newspaper reports at the time, killing somewhere between 80 and 250 people, among them many women, children, and tribal elders.

That was one life-searing overlay to Bartow’s personal history, whose genealogy also included the culturally similar, also northern Californian, Yurok tribe, but he also suffered other personal tragedies that he manifested through his art.

Bartow was a Vietnam war veteran who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. He was an alcoholic-in-recovery. His wife died of breast cancer. He had other health issues, including a severe stroke in 2013, from which he had to relearn many of his motor and cognitive skills.

In an earlier interview, Bartow recalled the horror first of experiencing, then trying to recover, from the stroke.

“Win, lose or draw, the brain is an absolutely awesome organ,” he said, referring to himself as “we,” to distinguish between himself before and after the injury. He described the experience as “having a portion of my brain dented.”

“I can no longer do some things with aplomb,” Bartow said then. “Some days really make me tired, trying to put sentences together. I want really hard to make my sentences cogent.”

S.B. (South Beach on Yaquina Bay) Owl, a Bartow monoprint from 2002; animals and birds were among his favorite subjects

For some time after the stroke, Bartow said he couldn’t speak intelligibly at all, just make sounds that he called “yabba yabba.” But what gave him hope for recovery came one morning when a nurse in the hospital happened to leave a pen on a bedside stand, where there was also a napkin. He picked up the pen, put it to the napkin, and drew a bird. At that point, he knew that “everything was going to be okay” — he could still draw.

Bartow died of congestive heart failure three years later, at age 69.

“I think as a result of all these challenges, there definitely is some heaviness to his work,”said Clarke, for whom this is the fourth showing of Bartow’s work in her gallery. “But there also is a great deal of his work that is charming and light-hearted. He was a very complex person, and of course that shows in his art.”

Bartow’s work received significant attention during his lifetime, including a commission to create two tall, carved wooden poles that stand on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of the American Indian.

But until the end of his life, he remained a simple, realistic, slightly irascible man. At the time of what turned out to be among his last gallery shows — one at the Karin Clarke Gallery and another at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon — Bartow spoke about his view of himself as an artist.

“I like to believe we all have a gift,” he said. “Mine is to make things. Others do (the) curating, printing, financial stuff — I make a mess and stay out of the way as best I can.”

In putting together this Bartow show, Clarke said she worked closely with Charles Froelick of the Froelick Gallery in Portland, which represents Bartow’s work.

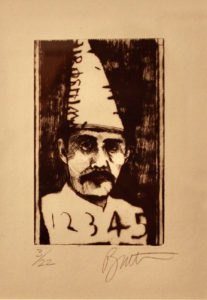

Conical Hat (3/22), a drypoint etching by Oregon artist Rick Bartow

“When I was choosing things, Charles (Froelick) reminded me not to just pick charming things, but to show Rick’s life in its complexity.”

As a result, the art in the show, titled Absinthe Dream, runs the gamut from life-affirming and even occasionally whimsical portrayals of animals — owls, coyotes, fish — to human portraits and half-human/half animal renderings reminiscent of his cultural upbringing.

Clarke vividly recalls an incident from when she visited Bartow’s studio before showing his work in 2015.

“He didn’t have a lot of stuff in his studio like most people would, just this one big piece tacked on the wall,” she recalled. “And he had something in his hand, and all of a sudden he did this spontaneous, huge scribble right across the painting, a big, swooping, staccato mark. It shocked me — I jumped and made a sound.”

What amazed her was that “he did it deliberately, and when I looked at it again it made the whole piece seem done — it was so sudden and unexpected, but as a piece of art, that one addition made it work. It looked like it needed to be there.”

To this day, she considers Rick Bartow to be “one of the most important artists to come out of Oregon.”

“I always had the impression that he didn’t have a big ego — he was just doing what he was and what he needed to be,” Clarke said. “I think he may be the most asked-about artist of anyone whose work I have ever shown.”

Absinthe Dream

When: Through Oct. 30, 2021

Where: Karin Clarke Gallery, 760 Willamette St., Eugene

Gallery hours: Noon to 5:30 p.m. Wednesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday

Information: Telephone 541-684-7963; email kclarkegallery@mindspring.com; online at karinclarkegallery.com