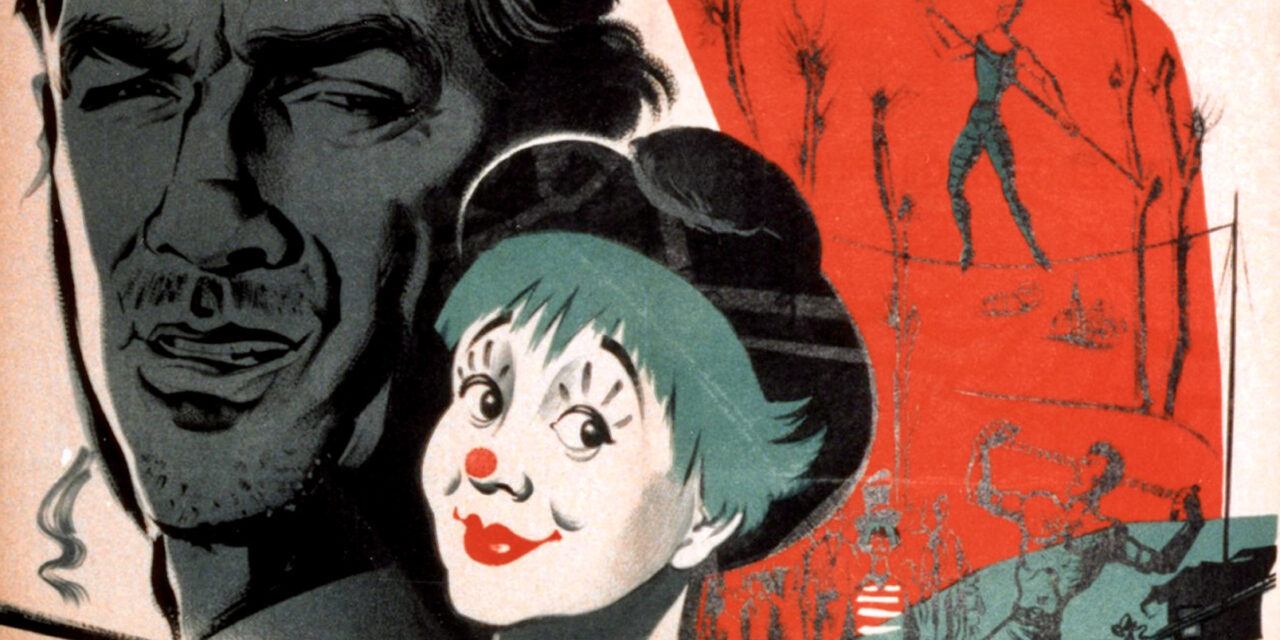

(Above: Poster for La Strada, one of Fellini’s most famous films, featuring Giulietta Masina, his wife and collaborator of 50 years.)

By Paul Carter

“All art is autobiographical. The pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.” — Federico Fellini

Out of the ashes of World War II, Italian filmmakers created a way of portraying life amid the ruin and poverty; to do it they invented the style called Neorealism. There was Rossellini, De Sica, Visconti and others.

And then came Fellini.

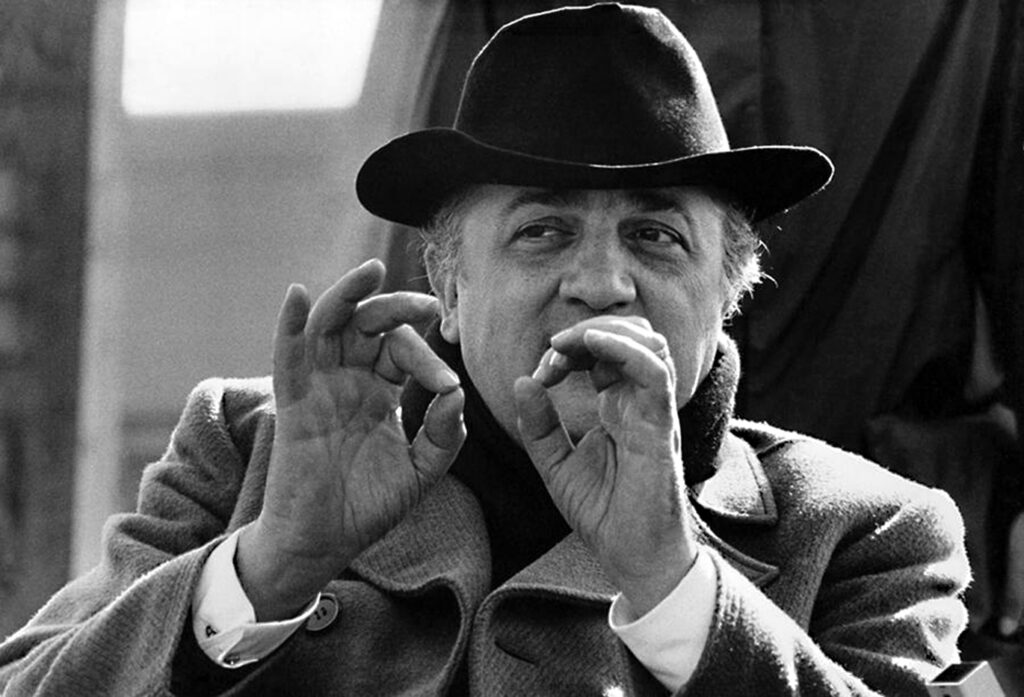

Federico Fellini was a middle-class kid from Rimini on Italy’s Adriatic coast. In the midst of war, he cobbled together a living as a newspaper reporter, a radio scriptwriter, even a vaudeville worker. Then he and several friends opened a shop in wartime Rome where Fellini sketched caricatures for American GIs. In his youth, his father wanted him to become a lawyer, but he had other ideas.

Federico Fellini and Giulietta Masina’s half-century marital and artistic partnership lasted until his death in 1993.

Before the war ended, Fellini met and soon married the woman who would be his lifelong muse and frequent leading lady, Giulietta Masina. They were together for 50 years.

His big break came the day director Roberto Rossellini came to the shop and proposed that Fellini help with the writing of a screenplay. The result was the script for the 1945 documentary, Roma Cittá Aperta (Rome, Open City). It was not a hit. Fellini persisted with a number of assistant directorial credits and then made The White Sheik. It too failed to impress the critics.

Then, in 1953, he made I Vitelloni (The Loafers) and that, a very autobiographical story, was an immediate hit.

The rest is not simply movie history. It marks the invention of a cinema all its own. For a movie to be described as “Felliniesque” is to be praised as magical, like the works of the auteur himself. Though many directors have grasped for the Fellini heights, none can claim their own adjective.

Now, in Eugene, we have an opportunity to feast on the works of the Italian master.

The Art House, formerly The Bijou, at 492 E. 13th Ave., launches screenings of a series of Fellini’s greatest films — 16 in all — starting Friday, Feb. 3, with La Dolce Vita. One hundred ten local cineastes contributed more than $6,500 to a Kickstarter campaign to finance the project. Bless them one and all.

It probably could not have been done without the campaign. As Broadway Metro and Art House managing director Edward Schiessl explains it: “With licensing fees in the thousands of dollars, programming a series is a big financial gamble, so that’s why we turned to a crowdfunding model. This way, we know in advance if we’ll have enough audience members showing up before we commit to the screenings — and folks are less likely to forget if they’ve pledged for their tickets in advance.” He also noted that several contributors like the idea of committing in advance to several movie night plans.

But why do we love Fellini? Moreover, why do directors such as Martin Scorsese, David Lynch, Guillermo del Toro and many others cite Fellini as an influence?

I think it is Fellini’s brilliant command of all the component parts of filmmaking.

Part of an art poster for Fellini’s 1972 film, Roma, which explored scenes familiar to him from his growing-up years in Italy’s capital city.

His themes dance between dream worlds and the ugliness of post-war life. His camera floats to unexpected vantage points or remains still in noir-ish, symbolic lighting. He used gritty locations which essentially became characters in his films. His casts included non-professional actors, and though he slaved over scripts, he also encouraged actors to improvise dialogue. His films could be his own therapy as he drew narrative threads from his life.

And then there are Fellini’s women. Some critics argue that many of his female characters betray in him a sexist attitude. And yet he directed his wife, Giulietta Masina, to sensitive performances.

And, finally, listen carefully. The memorable, evocative music that graces many Fellini films was the work of composer Nino Rota. They worked together for 25 years.

For the future at Art House, Schiessl has ambitious ideas.

“Our long-term plan is to run overlapping classic and cult-classic series throughout the year, and run a kickstarter for each one,” Schiessl said “This will not only afford us some financial security going into each series, but also allow us to gauge whether there is an audience for some more esoteric or obscure programming.”

“We plan to run overlapping cult and classic series staggered throughout the year, so probably about six to eight total series annually,” he said “We’re looking at some broader concepts for series such as great women directors, American musicals, film noir, and ’70s Italian Giallo horror.”

The Fellini program will run through May with 16 feature films. The series is more or less chronological, though it is bookended with two of Fellini’s most famous films, La Dolce Vita (1960) to begin and ending with 8 1/2 (1963).

The Fellini lineup

La Dolce Vita (1960)

- Friday, Feb. 3 at 6:30 p.m.

- Saturday, Feb. 4 at 1:30 and 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, Feb. 5 at 1:30 p.m.

- Tuesday, Feb. 7 at 7:00 p.m.

- Thursday, Feb. 9 at 7 p.m.

Juliet of the Spirits (1965)

- Saturday, Feb. 11 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, Feb. 12 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, Feb. 14 at 7:30 p.m.

Variety Lights (1950)

- Saturday, Feb. 18 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, Feb. 19 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday Feb. 21 at 7:30 p.m.

The White Sheik (1952)

- Saturday, Feb. 25 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, Feb. 26 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, Feb. 28 at 7:30 p.m.

I Vitellone (1953)

- Saturday, March 4 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, March 5 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, March 7 at 7:30 p.m.

La Strada (1954)

- Saturday, March 18 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, March 19 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, March 21 at 7:30 p.m.

Il Bidone (1955)

- Saturday, March 25 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, March 26 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, March 28 at 7:30 p.m.

The Clowns (1970)

- Saturday, April 1 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, April 2 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, April 4 at 7:30 p.m.

Fellini Satyricon (1969)

- Saturday, April 8 at 6 p.m.

- Sunday, April 9 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, April 11 at 7:30 p.m.

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

- Saturday, April 15 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, April 16 at 1 p.m.

- Tuesday, April 18 at 7:30 p.m.

Roma (1972)

- Saturday, April 22 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, April 23 at 2 p.m.

- Wednesday, April 26 at 7:30 p.m.

Casanova (1976)

- Saturday, April 29 at 6 p.m.

- Sunday, April 30 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, May 2 at 7:30 p.m.

Amarcord (1973)

- Saturday, May 6 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, May 7 at 2 p.m.

- Wednesday, May 10 at 7:30 p.m.

City of Women (1980)

- Saturday, May 13 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, May 14 at 1 p.m.

- Tuesday, May 16 at 7:30 p.m.

And the Ship Sails On (1983)

- Saturday, May 20 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, May 21 at 2 p.m.

- Thursday, May 25 at 7:30 p.m.

8 1/2 (1963)

- Saturday, May 27 at 6:30 p.m.

- Sunday, May 28 at 2 p.m.

- Tuesday, May 30 at 7:30 p.m.

Information and tickets: eugenearthouse.com/

(Above: Filmmaker Federico Fellini (1920-1993). Six months before his death, Fellini was awarded his fifth Oscar, for lifetime achievement. He died one day after his 50th wedding anniversary to muse and spouse Giulietta Masina. His memorial service in Rome was attended by an estimated 70,000 people.)