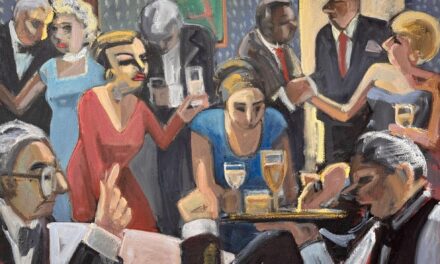

(Above: Camel caravan crossing the Teel River in Mongolia; photo by Gary Tepfer)

By Randi Bjornstad

Photographer Gary Tepfer’s career took a decisive turn 20 or so years ago when his wife, surface archaeologist Esther Jacobson-Tepfer, announced that she needed a landscape photographer to work with her.

He already was an accomplished landscape photographer, but photographing for surface archaeology is something else again. It involves a painstaking process of discovering and creating a photographic record of physical objects and other signs of habitation on the surface of land, left behind by inhabitants ranging as long ago as prehistoric or simply so isolated that the regions they have occupied have never been mapped.

The result has been decades of traveling, observing, and cataloguing vast, nearly empty areas in the region of the Altai Mountains, in a rectangle of 326,000 square miles that includes portions of Mongolia, China, Russia and Kazakhstan.

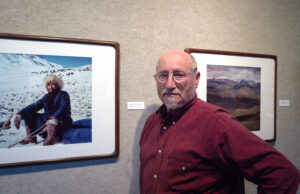

A show of Gary Tepfer’s photographs from his scientific travels to Mongolia document the lives of the people there; photo by Paul Carter.

A new show of his work reflects the images he has taken for purposes of documenting surface archaeology, but it also shows his deep interest in the people and sweeping landscapes of countries, like Mongolia, that most people never see. Views of a Herder’s World: Landscape and Culture in the Mongolian Altai is on display at the White Lotus Gallery in downtown Eugene through July 8.

It has not been easy.

“Lots of these places have no roads or bridges, at most a track to follow,” Tepfer said. “And there is a great deal of sensitivity in that area about borders. In many cases, foreigners are not even allowed to go there.”

That proscription was most severe before 1985, but changed somewhat when Mikhail Gorbachev became the leader of the Soviet Union and instituted policies of glasnost, which included opening up remote areas of Russia to greater scientific and educational cooperation and sharing of information.

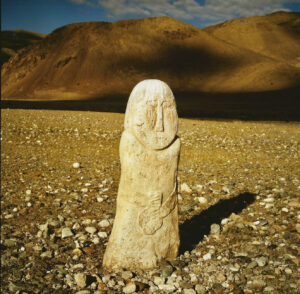

Ancient Uyghur rock art found in a remote rectangle of the Altai Mountains may be the most extensive in the world; photo by Gary Tepfer.

Surface archaeology was one of the great beneficiaries of those changes, Tepfer said, although that didn’t mean it became easy. But the discoveries were immense, including the chance — and responsibility — of documenting “probably the highest concentration of rock art in the world,” he said. “The native herders who lived there knew all about about it, but they represent only a very few people in a very huge area.”

Rock art by definition includes designs carved, drawn, painted, engraved on hard surfaces, either vertical or flat, or patterns simply laid out on the ground using objects such as rocks.

When Jacobson-Tepfer and Tepfer began their decades of collaboration, they spent 10 years surveying and documenting just one area and six years in another.

“Mongolia was the center of this wonderful tradition of rock art and surface art,” Tepfer said. “It was also more complicated because there were no good maps of this huge area.”

To address that problem, Jacobson-Tepfer linked up with James Meacham, a research cartographer at the University of Oregon and co-founder of the UO’s InfoGraphics Lab, who accompanied her and Tepfer to Mongolia. They created their own maps of the area by averaging measurements obtained from a prototype Global Positioning System, or GPS, “while I did black-and-white and color photographs of everything every day,” Tepfer said.

From music to photography

Tepfer didn’t start out to be a photographer. As a very young man, he was an outdoor recreational guide in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, but his father taught him how to use a Rolleiflex camera, and he bought one of his own when he was 19.

Up to that point, Tepfer, who was proficient at viola, had thought he would be a musician. But he became enamored of photography “when I realized that I saw more in my photographs than I actually saw with my own eyes, and at 25 I decided I would make photography my profession.”

He went to New York City, where he learned the craft and practiced commercial photography, but his heart remained with the out-of-doors, and he turned to landscapes as a specialty.

In Oregon, his first exhibit was at a Eugene business called Solid Ingenuity, “and then I started doing exhibits in Portland, San Francisco, and then in galleries throughout the country,” he said, including the White Lotus Gallery, where he is a represented artist.

The work that has resulted from his trips with Jacobson-Tepfer are a high point of his career, Tepfer said. “From that extended experience, (we) have come to understand the essential intersection of landscape, environment, and cultural change.”

What began as a project joining his photography and her scientific research related to monumental archaeology “have proved to be one of the most significant experiences of our lives,” he wrote in his artist’s statement.

“The land in which we worked, the friendships we developed, and the opportunities to observe and participate in the daily lives of Altai herders profoundly affected the way we looked at their world and its rich cultural remains.”

Tepfer last went to Mongolia in 2010, although Jacobson-Tepfer returned in 2016, as part of a successful effort to achieve World Heritage Site status for three locations where they had done research and photography, from UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

“She went to the conference, having no idea that it was going to include giving her the Kublai Khan Gold Medal for contribution to Mongolian heritage,” Tepfer said.

Tepfer photographed many of the herders and their families in Mongolia; this sleeping baby in its basket had just been unloaded from a camel’s back.

One of his favorite memories of meeting the ordinary people in the places they traveled was that he was able to give them something many had never seen before.

“When we worked in the field, I would take pictures of people, and then when we would go back a year or so later, I would give them prints of themselves,” Tepfer said. “Many of them had never seen a photograph of themselves before, and some would say, ‘The quality is good but the service is slow.’

“And the amazing part was, even though most had no experience with being photographed, they seemed to have an innate ability of how to pose for a picture.”

Views of a Herder’s World: Landscape and Culture in the Mongolian Altai, photographs by Gary Tepfer

When: Through July 8, 2023

Where: White Lotus Gallery, 767 Willamette St.

Gallery hours: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday

Information: Telephone 541-345-3276; email lin@wlotus.com or online at wlotus.c0m

Above: Blue Lake Chikuchova 1993, one of photographer Gary Tepfer’s favorite photos from his trips to Mongolia