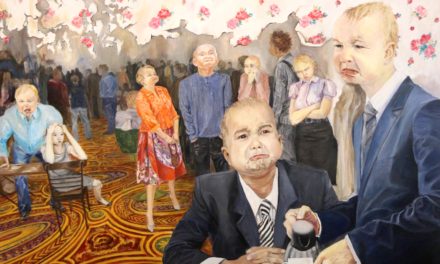

(Above: A detail from a stained glass window created by artist Chuck Franklin for a woman who commissioned it because, she said, “Whales have always been a part of my life;” photo by Chuck Franklin.)

By Jordan Essoe

WALDPORT – At first it sounded good to finally set his grozing iron down.

After more than 40 years of around-the-clock work, it seemed reasonable. Who wouldn’t be a little burnt out from so many years of relentless deadlines?

But some shops just won’t stay closed.

Following three years of tending to the yard and assembling model trains in a spare bedroom, the inevitable happened. The grozing iron and the wheel cutter and the leading and the solder all found their way back onto stained glass artist Chuck Franklin’s worktable.

“I started to really miss it,” said Franklin, now in his mid-70s, and who’s once again running a glass arts studio out of his garage, just like when he first started out.

At the summit of his career, he presided over a 13,000-square-foot Portland studio with twenty employees, juggling uninterrupted commissions from casinos, churches, libraries, and restaurants nationwide.

Sometimes executing designs for full dining rooms or multiple interlocking social spaces, he and his team produced everything from Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired exterior windows and Tiffany-inspired lamps to a stylistically diverse array of skylights, complex multi-tiered lights and sconces, signs, backlit panels, partition windows, and intricate ceiling installations – including glass domes as large as 60 feet in diameter.

The artist even has rendered himself in stained glass; this piece, created in 1978, still hangs in his family home; photo by Jordan Essoe.

In addition to the technical and creative work, there were constant meetings and plane rides for overnight stays in cities far from home. He made good work, made good money, received a lifetime achievement award, and was the focus of a small press book.

Trying out retirement

In 2015, it was supposed to be time to shutter his practice, and Franklin and his wife Carol moved from Portland to a quiet home in Waldport near Eckman Lake.

But now, Franklin has returned to work. His current schedule of comparatively modest, local commissions represents more than just a scaled-back operation with more flexible deadlines. Most importantly, he now has more creative freedom.

“When my studio was at its height, I was definitely restricted on what I was doing. There wasn’t always room to create things that I wanted to,” said Franklin. “People here on the coast like my work and give me a real freedom to do something that I want to do.”

Franklin still does some limited commercial work, but he is mostly making custom stained glass windows for private homes.

“I do a lot of things that are contemporary,” he said, “but also have the feel of the coast, and water and nature. Something flowing and stylized.”

Clients tell him roughly what they want, and they discuss shapes, colors, and style. He produces a pencil sketch of a proposed design and shows a few samples of potential glass before completing a final ink drawing. He never gives a client a finished color plan, but instead resolves those decisions in the creative privacy of his home studio.

Franklin says some clients want to pick out exactly what colors of glass will be cut, but he won’t work that way.

“That would be like hiring a painter for a portrait and telling them which tubes of paint they should use,” Franklin said.

Many people still associate stained glass mainly with places of worship — specifically the pointy-arched, flying buttressed Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages. When South Beach resident Patty Bishara commissioned Franklin to make a transom window over her patio door, one thing she relayed to him in their first conversation was that she didn’t want anything “churchy.”

Whale watching has been a longtime passion for her, and she wanted something that would bring part of that aquatic world indoors. After interviewing her, Franklin connected the idea of migrating whales to the importance of the relationship between Bishara and her only child, a son now living abroad.

The completed window features two whales swimming closely together to reflect the bond between mother and son.

Bishara says Franklin’s window integrates perfectly into her home and her style. “It’s become a part of me,” she said.

While not presenting the same engineering contest as a 60-foot ceiling dome, the process of adequately reinforcing windows for tough coastal weather does provide its own variety of installation challenges.

For an oceanfront house, Franklin recently designed a north facing deck window with holes cut in its face to relieve pressure from the wind. The holes had to be placed strategically so that the desired privacy the window was intended to provide wasn’t compromised.

Franklin likes that his work has practical, unromantic elements to it — that what he makes is not just artwork, but also serves a concrete purpose. He says clients are often very interested in increasing privacy or reducing light as much as they are interested in beautifying a space.

This glass panel was inserted inside an original door in a Yachats home. Some neighbors initially balked, but several since have hired artist Chuck Franklin to create artwork for them; photo by Chuck Franklin.

He has worked a lot in the Koho neighborhood in Yachats, where all of the homes have full-length windows set in their front doors.

“The problem is anybody can walk up and just look inside the condos,” said Franklin. “So I’ve used very textured glass that gives people the privacy they want.”

Karen Hawkins, the first Koho homeowner to have Franklin install stained glass in her front door, said there were initially some complaints from neighbors that the change violated the neighborhood’s Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions, or CC&Rs.

Hawkins, who was then president of the development’s homeowners association, pointed out that the original glass door is actually untouched — Franklin mounts his stained glass on the inside to protect it. Franklin’s second Koho customer was the chair of the architectural review committee, and many others also have since hired him.

“He’s just the sweetest man,” Hawkins said of Franklin. “Very eager to please, very easy to work with.”

When they discussed designs, she told him she preferred clean lines in a Frank Lloyd Wright style and found examples in his portfolio of previous work that echoed that.

Laughing as she recalled their initial conversation, Hawkins said, “The first thing I said to him was, I don’t want any little mermaids and dolphins. I want something a little more adult than that.”

Hawkins enjoys not only how the window looks on the inside, but how all the Koho stained glass doors appear from the street at night, lit from within.

Still hard at work

One of Chuck Franklin’s more recent works is a 20×30-inch glass for Cafe Chill in Waldport; photo by Jordan Essoe

One of Franklin’s more recent works is a 20×30-inch window for Cafe Chill in Waldport. It is a trace reminder of his extensive and personally meaningful history making glass for the restaurant industry.

Franklin’s very first stained glass piece was created for a restaurant. It was a fluke at the time. When he was asked to do it, he didn’t know how to make anything out of glass.

It was 1974, and Franklin was living in a friend’s garage, had been selling homemade candles out of the back of a bus, and had recently taken up making wood carvings.

A friend was opening a tavern in Tualatin, Oregon, and offered to pay Franklin to make a wooden tavern sign, restroom door signs, and draft beer tap handles. He also thought it would be cool if Franklin made a stained glass saloon sign to hang behind the bar.

The artist taught himself how to create stained glass art; his very first job led to a commission for a venerable Portland restaurant, and his career was born; photo by Chuck Franklin. The restaurant is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Franklin taught himself how to make stained glass. He made the saloon sign and a couple of stained glass lamps. Shortly after the tavern opened, he made a connection that would change the course of his life.

“After I’d made the few glass works for this tavern, somebody left a note for me on a bar napkin,” said Franklin. “It had the name of a place downtown and a phone number.”

The place written on the napkin was a well-known Portland restaurant dating back to 1892 called Jake’s Famous Crawfish. It still exists today. Then-owner Bill McCormick, who unbeknownst to either of them would soon become extremely successful in the restaurant business, asked Franklin to do one window for him.

“I was very lucky,” said Franklin. “That was my first commercial piece, and it got the ball rolling.”

Several years later, McCormick partnered with manager Douglas Schmick to open a restaurant chain called McCormick & Schmick’s Seafood Restaurants.

“The architect loved stained glass, as did Bill and Doug,” said Franklin, “so I did work for McCormick & Schmick’s for 35 years and for about 130 restaurants all around the country.”

McCormick & Schmick’s remained Franklin’s No. 1 client for decades, until the business was taken over by wealthy Texas restaurateur Tilman J. Fertitta. Once that happened, Franklin said, things went downhill.

It wasn’t just that the glass commissions from the seafood restaurant company stopped. It got worse. An unsettling percentage of Franklin’s unique glass creations, equaling the lion’s share of his studio’s output for so many years, were removed or destroyed.

Franklin had contractors he didn’t know calling him up and saying “I’m being asked to throw this away, and it looks expensive – do you mind if I hang onto it?”

Franklin would respond “I got paid for it, help yourself.”

But it’s not great to think of your life’s work being thrown out with the garbage or picked over like carrion. Franklin said casinos are also notorious for doing the same thing, instituting a design change and getting rid of most of the existing work just to freshen the way the place looks.

Now in his mid-70s, artist Chuck Franklin still enjoys creating his art and has a backlog of commissions. “Other people on the coast do blown glass or fused glass,” he said, “but I’m the only one in the area doing custom stained glass work;” photo by Jordan Essoe.

On the other hand, there is at least one place where everybody still knows his name.

“It turned out the first professional work I ever did — for that restaurant Jake’s — is now on the National Register of Historic Places,” said Franklin. “And none of my work in there can really be touched. So that’s one job that will outlive me for sure. I kinda dig that, actually.”

For new commissions, Franklin currently has a backlog of a couple months. He says most people are understanding that he is quasi-retired and he sees himself as serving a unique role in the community.

“It’s nice to be able to do things for people, and take advantage of a lifetime of doing it. I don’t work as fast as I used to,” Franklin said. He paused a moment, then added with a smile, “but I still work faster than most people.”

About the author: Jordan Essoe is an award-winning artist and writer who has exhibited and published internationally. Primarily a painter and performance artist, his practice broadened to include film, playwriting, and journalism. His work has been covered by NPR, the Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle. He was born in Los Angeles County, raised in a small town in the San Bernardino Mountains, and currently lives on the central coast of Oregon.