(Above: Returning Home, a painting by David Diethelm)

By Randi Bjornstad

Gladiolus Spectacular, photograph by David Diethelm

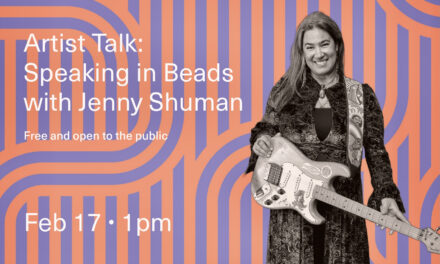

David Diethelm is an artist. He’s also a book publisher, book illustrator, fine art photographer, and marketer who makes his artistic images available for purchase online, on everything from art prints to tapestries to cellphone cases to jigsaw puzzles to tote bags.

“I’m trying to get my art out more,” says Diethelm, who grew up in Eugene from the age of two, graduated from South Eugene High School in 1987 and then combined studies in fine art and design at the University of Oregon, along the way becoming proficient in page layout, three-dimensional modeling, and animation “back when ‘tech’ was very different from the way it is now.”

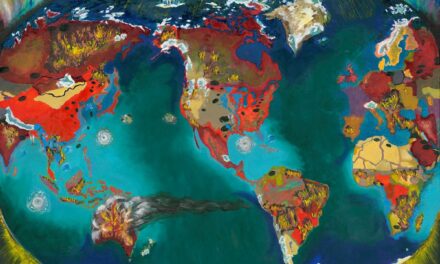

“I liked to come up with geeky and fun ways to do things that otherwise couldn’t be done without experience in software development,” he says. That included working in a research lab on a project called the Willamette River Basin Planning Atlas, which was published in 2002 by the Oregon State University Press, described then as including “a dazzling variety of color maps, charts, and photographs (that) provide a long-term, large-scale view of changes in human and natural systems within the basin,” from 1850 to the present as well as offering three future scenarios depending on a range of environmental policies.

Later, those same skills led Diethelm to collaborate with Chet Bowers — an educator and environmental activist and also a friend of Diethelm’s father, architect and landscape architect Jerry Diethelm, who taught land-use planning and design at the UO for 35 years — to form the Eco-Justice Press.

On the Edge, a painting by David Diethelm, recalls the Oregon wildfires of the summer of 2020

“Chet was a friend of my dad’s — his wife had been my teacher in third and fourth grades here in Eugene — and he got back in touch about 10 years ago because he wanted to publish his own books,” Diethelm recalls. “I didn’t know a lot about publishing, but I learned, and we published about four of his books. We started Eco-Justice Press in 2010. I bought his share before he passed away in 2017. It’s pretty much been going along since.”

So has his painting, which he has been able to spend more time doing in the past year because of the seclusion imposed by the coronavirus pandemic.

“I can have a regular routine at home, and it has helped a lot to be able to go up and paint and not feel that I have to do anything else,” Diethelm says. “Sometimes something doesn’t seem to be working, and then I just go do something else, like reading a book, reading online, or making sketches on a page with little boxes. I usually start by doing 4×4-inch doodles and then going on from there.”

His mediums primarily include oil, watercolor, and pastel, and more recently, encaustic, which consists of hot beeswax colored with pigments. “It’s fun to experiment with new processes, new techniques,” he says.

“I’ve always been intrigued by line work, trying to translate drawings into paintings,” Diethelm says. “Sometimes I do a sketch, then I paint to a certain point and come back later to add more colors to interact with the previous layers, by using a palette knife to scratch and reveal what’s underneath. To me, that adds an organic quality.”

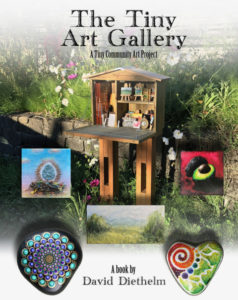

David Diethelm created the Tiny Art Gallery to promote interest in creation and sharing of art within neighborhooods

His interest in trying new techniques led Diethelm three years ago to create what he called a Tiny Art Gallery, based on the concept of the Little Free Library program that now has more than 100,000 installations in more than 100 countries worldwide,

“I got the idea that it would be good to have a similar thing, only with art instead of books,” Diethelm says. “I thought first it would be good not to just share art but to have people interact by creating their art and then sharing it.”

He found a wooden box online, ordered it, and and put it out in his College Hill neighborhood with art supplies that people could borrow, use, and then return, along with tiny pieces of art to show and share.

“My idea was to photograph the art that came and went from the Tiny Art Gallery and do a book every year or so with the artwork that people put in it,” Diethelm says. “There was quite a bit of interest in it, and the people in the neighborhood really got into it.”

Another neighbor started a tiny gallery also, he says, and then a woman in Florence wanted to do one, too.

“That was all really cool, but then someone vandalized and completely my Tiny Art Gallery,” he says. “After awhile, there was a little fundraiser to do another one — in metal so it couldn’t be taken out — and a local business guy offered to do the sides and roof. But then covid-19 hit, so it’s still kind of in progress. I hope to get back to it as things improve.”

When he first started the Tiny Art Gallery, “I thought of it as kind of a social experiment,” Diethelm says. “But it lasted a long time, and when it was broken, there was an outpouring of community feeling that people really valued it, and we needed to bring it back. And we will.”

He especially remembers a 2-year-old toddler in the neighborhood who did one of the first artworks to appear in the original Tiny Art Gallery and later in Diethelm’s book about the project.

“I told him that now he was a published artist,” Diethelm recalls. “He has continued to be interested in art ever since. He made cookies for me on the day it was destroyed.”

More about artist David Diethelm

A sidewalk show of a few of David Diethelm’s landscapes