By Randi Bjornstad

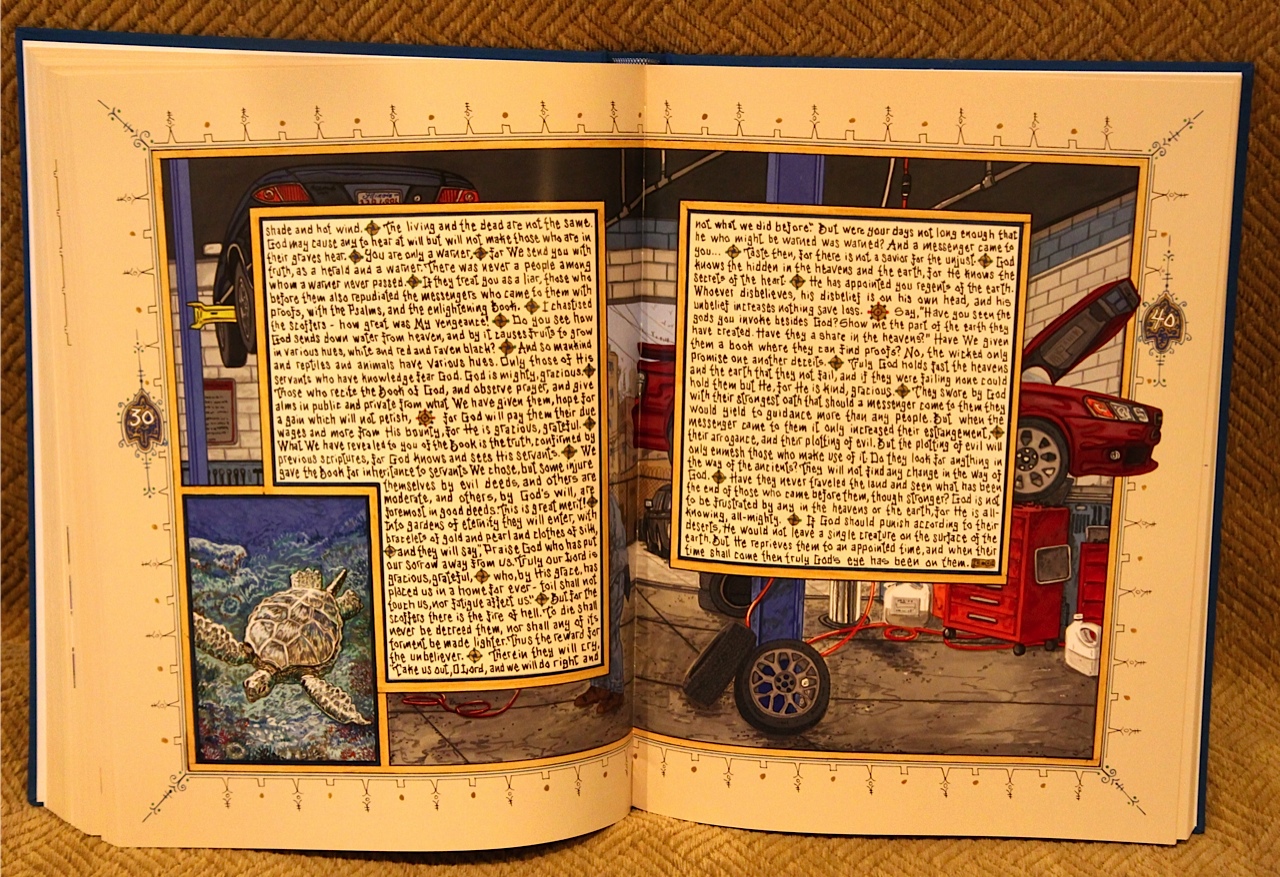

As TheEugeneReview.com’s first story said about “American Qur’an,” Sandow Birk’s book is “gorgeous, thought-provoking, weighty — symbolically and literally, weighing in at 12 pounds — and without a doubt, one of the most important and satisfying, not to mention impressive, books that many in this country could hope to read this year.”

After having it in my own home library since then, and given the controversial events that have transpired in the interim, I’d say those words are even truer now.

The original story appeared in January when the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon opened its “American Qur’an” exhibit, and this one appears just days before the end of the show on March 16.

The artist never dreamed his rendition of the Qur’an, in text and pictures, would take a decade to complete

Artist Sandow Birk was in his mid-40s when he started working on this project, and he turns 55 this year, so it’s obviously been a labor of love as well as artistic and philosophical commitment.

Birk came to Eugene when the exhibit opened, and he’s making a return appearance on March 9 to talk about his book again. Much has happened since then, making his effort to express pictorially the values and texts of the Muslim holy book in terms of everyday American experience not only more urgent but also more poignant.

As Jill Hartz, executive director of the Schnitzer museum, explained his project at the time of the opening, “He embarked on ‘American Qur’an’ because he wanted to learn more about Islam, partly because of the Sept. 11 tragedies and partly because he had always been a surfer and had visited many Muslim countries as he traveled the world, looking for the best waves.”

Birk’s art always has centered social action, Hartz said, including the depravities of war, the cultures of California prisons and mining disasters. He did a set of wall-sized woodblocks of the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.”

In advance of Birk’s return to Eugene for his second artist’s talk, here’s an up-to-date Q&A about him and his project, followed by a reprint of TheEugeneReview.com’s original story.

Randi Bjornstad: Of course, much has happened since you were here before the opening of the show, and I wondered if you have any changes of thought about the relationship between current events and your work and how you would like people to look at and think about “American Qur’an.”

Sandow Birk: The unfortunate thing is that when I began this project there were comments like, “it’s so timely”, and then I work on it for ten years and people say, “it’s so timely.” So not a lot has changed in the way Americans perceive and fail to understand Islam as a religion, and I think things are worse in the last three months. It’s very sad, and I find myself depressed the direction this nation seems to be heading. It’s sad. I had expected and believed that we were a better nation, moving towards equality and globalism and a more caring and understanding as a people. It turns out that’s not the case for much of our countrymen.

Bjornstad: Spending 10 years doing a project like this book is such a monumental commitment. Did you realize at the outset that it would be that intense and longlasting? How did you approach the text in the context of dividing it into portrayable sections, and how did you choose how to match that with scenes/attitudes from American life?

Birk: The initial idea for the project and the initial vision was to create an illuminated manuscript of the entire Qur’an, like was done in the Middle Ages. Every word, every page. So of course I knew it was going to be an engrossing project if I began it, and I knew that I had to finish it if I began. So yes, I did know it was going to be big. At the outset I estimated it would take me about four years, but after four years — when I thought it was going pretty well — I took stock of where I was and it turned out I was only about halfway through, and that was sort of depressing, to realize that it was going involve so many more years of my focus and art practice.

My final book composes the entire Qur’an, each page hand-lettered in English. The translation was taken from a copyright-free, existing English translation, and I mostly consulted Muhammad Asad’s translation and that of Thomas Cleary. The layout of the pages is taken from a thousand years of historical koranic manuscripts, using the traditional format, border decorations, the method of marking verses with floral

Sandow Birk hand-wrote the entire text of the Qur’an and illustrated each page with a scene from contemporary American life

medallions, and so on. Then each image is a scene of contemporary life in the United States which is a visual metaphor for passages of the text which appear on that same page. Sometimes that metaphor is clear and simple, such as scene of the flooding of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina that appears along with passages which talk of Noah’s Ark. Sometimes the metaphors are more obtuse and hopefully thought provoking.

Bjornstad: Are there any pages of your work that represent to you more emotionally than others what you hoped to achieve with this body of work? Has that changed at all since the book was published, given changes in world and U.S. politics and attitudes?

Birk: It’s hard to pick out favorites from an enormous project and 440 some pages, but I think as a whole it works well. What I hoped to do was to take what I would argue is the most important book in the world right now, for many reasons and better or worse, and make it more accessible. After all, Islam is a religion that spans the planet, on every continent and across cultures, and yet the vast majority of Americans have no inkling what it’s about or what it says in the Qur’an, as I didn’t before I began this project.

The Qur’an, Islam’s holy book, has many entries that parallel those of Christianity, including this one, about Mary, mother of Jesus

And if you spend even a few moments with it, you’ll find that the message of the Qur’an is remarkably familiar — the story of Adam and Eve, Noah’s Ark, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Mary. It’s not some crazy, unfathomable thing. So by showing our daily lives alongside its message, I hoped to show that it can resonate with us, with our lives, that its message is something that we can understand and relate to and not that its some foreign thing from some other culture in the Middle East. After all, the Bible is a book from the Middle East, from nearly the same place as the Qur’an, but we think of it as a global message, not as Middle Eastern. Well, for a billion people, the Qur’an is the same thing. After all, about 80 percent of Muslims do not live in the Middle East, nor do they speak Arabic, so thinking of Islam as “Middle Eastern” is a unreal as thinking that Christianity is “Middle Eastern”.

Bjornstad: Will you ever do another project this intensive, do you think? What are you working on now?

Sandow Birk’s “American Qur’an” weighs in at 12 pounds and measures 12×16 inches in size

Birk: I really can’t say — most of my projects just start out as the spark of an idea, and I have no idea how big they are going to get at first. The exception to most of my work has been the “American Qur’an,” which I knew before beginning work on it that if I started and I was going to have to see it all the way through to the end. So, no, I don’t have any massive projects in mind just yet, but I wouldn’t say never.

And actually, my wife, Elyse Pignolet, and I are just at the beginning of a project to create a 40-foot-long woodblock print which is going to be a big project. It could be that it’s more than we expect and it will be another huge endeavor, but at this point it seems like it will only take a few months. So that woodblock print — which is a procession of historical American figures — is one project that is going on right now.

My wife also is in the middle of big ceramic tile mural project for the city of Los Angeles for a public pool. Then I’m working on paintings for a show in the summer, and then we go to New Zealand to do an artist-in-residency stint at the University of Auckland all summer, so I guess there’s a lot of projects going on. But that seems normal to us. Its when we’re not working on stuff and don’t have things lined up that I get nervous and stressed out.

American Qur’an

When: Through March 19

Where: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, 1430 Johnson Lane, University of Oregon campus

Museum hours: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Wednesday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday through Sunday

Information: 541-346-3027 or jsma.uoregon.edu

Remaining “American Qur’an” events:

* Artist’s Lecture by Sandow Birk — 6 p.m. on March 9, 177 Lawrence Hall, UO campus

* Sandow Birk: “American Qur’an” — 5:30 p.m. on March 10; lecture by Zareena Grewal, associate professor of American Studies and Religious Studies at Yale University, followed by conversation with Sandow Birk

TheEugeneReview.com’s original story about “American Qur’an,” posted on Jan. 19, 2017:

By Randi Bjornstad

It’s gorgeous, thought-provoking, weighty — symbolically and literally, weighing in at 12 pounds — and without a doubt, a book called “American Qur’an” should rank as one of the most important and satisfying, not to mention impressive, books that many in this country could hope to read this year.

“American Qur’an” also is the title of a new exhibit opening at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon with a public reception on Jan. 20 and a gallery tour with the artist followed by a panel discussion on Jan. 21. The show will be on view through March 19.

It’s the work of artist Sandow Birk, who turns 55 this year and has spent his career visually plumbing the effects of war, propaganda, inner-city violence, politics, graffiti and the meaning of contemporary American life.

But he also has addressed lighter topics, including skateboarding, surfing and other elements of American culture.

This book came out of the darker tradition, following the epic tragedy of Sept. 11, 2001, when Middle Eastern hijackers succeeded in commandeering four commercial aircraft and crashing them into both World Trade Towers in New York City, the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., and a field in Shanksville, Pa. Nearly 3,000 people died, and 6,000 more were injured.

Jill Hartz, executive director of the Schnitzer museum, has followed and admired Birk’s work for many years.

“He embarked on ‘American Qur’an’ because he wanted to learn more about Islam, partly because of the Sept. 11 tragedies and partly because he had always been a surfer and had visited many Muslim countries as he traveled the world, looking for the best waves,” Hartz said.

“His work almost always centers on social action projects — he has focused on the depravities of war, the cultures of California prisons and mining disasters. He did a set of wall-sized woodblocks of the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.”

Birk’s idea of illustrating the Qur’an was different, however, Hartz said.

“With this project, he wanted to go beyond the fact that the United States has been at war in predominantly Muslim nations for over a decade,” she said. “He wanted to show that the text of the Qur’an contains principles and values that apply to all nations. And he wanted to do it in a way that Americans, who don’t know much about the Qur’an or the Muslim faith, could understand and appreciate it.”

He did it by working with existing, official English translations of the massive text, writing the entirety of the words in a graffiti-like calligraphy and illustrating the pages with artwork that drawls parallels with the American experience.

For example, the text telling of the Annunciation of Mary by the Archangel is portrayed by a pregnant woman receiving an ultrasound. The story of Noah and the Flood is illustrated by a scene representing Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. The section dealing with resurrection and the afterlife shows doctors resuscitating a patient who has flatlined.

Artist Sandow Birk interprets one section in “Qur’an America” with a picture of a U.S. political convention. Other pages of Qur’anic text are accompanied by pictures of farm workers, governmental services and everyday activitites.

Each of the 50 United States is represented somewhere in the book.

The hefty undertaking took Birk a decade, as those familiar with his work waited eagerly for the result.

“We’ve been seeing pieces of ‘American Qur’an’ for the past seven years, and all of us were wondering when it would be ready,” Hartz said. “The book was finally published in 2016.”

In anticipation, it was named one of the best books of 2015 by Publishers Weekly. The volume, which measures 12-by-16 inches, costs $100.

The resulting art exhibit, which consists of hundreds of pages of illustrated text, has not been without controversy.

“The Orange County Museum of Art was the first to show it, and we were going to participate with them in creating a traveling exhibit, but no other museums agreed to pick it up, so it is coming to us next and will be here for two months,” Hartz said.

Many of the Qur’an’s descriptions an admonitions mirror those of other major religions

In addition to nearly 200 of the ink-and-gouache images, the show also will feature two other large paintings, one a Jacques Cousteau-type painting of underwater research and one of a Russian astronaut, Yuri Gagarin.

“The idea is to portray humanity in terms of the depth of the ocean, the depth of space and the depth of the spirit,” Hartz said.

The exhibit also will include ceramic depictions of the mihrab, the semicircular niche that indicates the direction of Mecca and, therefore, the way people of the Muslim faith should face when praying.

Even so, the overall show should not be considered a religious show, partly because of the English translation of the text of the Qur’an.

“To be considered the direct revelation from God, the text must be written in Arabic, which was Mohammed’s language,” Hartz said. “This is an opportunity for people in this country to learn about the verses of the Qur’an in the context of their own lives and culture.”